Abstract

This observational study examined the the risk factors of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) among Indians and Nepali’s living in the North Carolina and Virginia (US) and how their lifestyle and family history impacts their health.The data was collected through a survey sent out to 50 participants, which asked about their country of origin, years in the US, gender, age, and weight. Then, we measured health conditions such as DM, Hypertension (HTN), Dyslipidemia, stroke, and heart disease. Findings suggest that South Asians in the US tend to have normal cholesterol, hemoglobin, HbA1c, and fasting glucose levels. When looking at diet and lifestyle, most people followed an Indian Diet, fasted a few times a year, did not consume sweet beverages, drank coffee, ate nuts and fruits, and consumed tea. Most respondents were from India and aged 38-50, within normal ranges of weight and BMI. This result contrasts with the South Asians living in their country of origin. The results help us conclude that many issues in the populations, such as elevated cholesterol levels, obesity, and more can be correlated to poor diet choices with high carbohydrates and fats, which the “Indian Diet” presents. In addition, middle-aged participants (most surveyed adults) face increased susceptibility to prediabetes due to elevated fasting glucose levels (100-125 mg/dL) and HbA1c levels (5.7-6.4%). These high levels can contribute to lifestyle factors, such as poor physical activity, alcohol consumption, and unhealthy diets.

Key Words: Diabetes Mellitus (DM), Pre-Diabetes, South Asian Community, United States (US), Risk Factors, Beta Cell Function, Insulin Resistance, Obesity, High-Glycemic Index Foods, Hypertension (HTN), Dyslipidemia, Heart Disease, Stroke, Indian Diet, Western Diet, Exercise, Intermittent Fasting, Alcohol Consumption, Family History, HbA1c Levels, Cholesterol Levels (HDL, LDL), Hemoglobin, BMI, Primary Care Physician Visits, Dietary Habits, Urbanization & Development, Self-Reported Data, Epidemiology, Genetic Mutations, Lifestyle Choices, Public Health Implications.

Background

In general, South Asians are more prone to diabetes than any other ethnic group, with a 27% prevalence of Type 2 Diabetes in South Asians compared to 8% of non-Hispanic white individuals.1. One reason that can explain this is that mutations acquired in various genes required for proper beta cell function2. These mutations could have come about for many different reasons such as famine or lack of food, making their bodies adapt so they can store optimal amounts of fat.3 With modern trends of urbanization and development, however, this trait proves disadvantageous, leading to increasing obesity and risk of insulin resistance and diabetes. Additional studies4 , have also shown that South Asians have lower beta-cell function (cells in charge of producing insulin in the pancreas), leading to less insulin production and higher blood sugar levels.

Another factor that plays into the higher prevalence of diabetes in South Asians. When in their home countries such as India, Nepal, and Pakistan, the diet is primarily South Asian rather than a mix of Western and South Asian, like most in America. The main nutrients of South Asian foods include Carbohydrates from Grains such as rice and wheat, protein from Lentils and Meat, Vitamins from spices and vegetables, and fats.5. Specifically, South Asians consume a lot of High-Glycemic Index Foods, which have a higher prevalence of fasting glucose which increases the chances of diabetes.6. In addition, most South Asians tend to be less physically active due to the culture and ideals of lifestyle built in India (fitness is not a big priority there).7’8.

Through Diabetes, South Asians are also at risk for different health complications. The biggest potential health implication could be cardiovascular diseases such as stroke, coronary artery disease, and heart failure. High Blood Sugar levels caused by diabetes can damage the lining of blood vessels, making them more prone to plaque buildup.9.This plaque buildup can narrow arteries, reduce blood flow, and increase the risk of a heart attack. Diabetes can also lead to abnormal cholesterol levels, including high LDL and low HDL, which contribute to atherosclerosis (buildup of fats, cholesterol, and other substances in artery walls).10.

Method

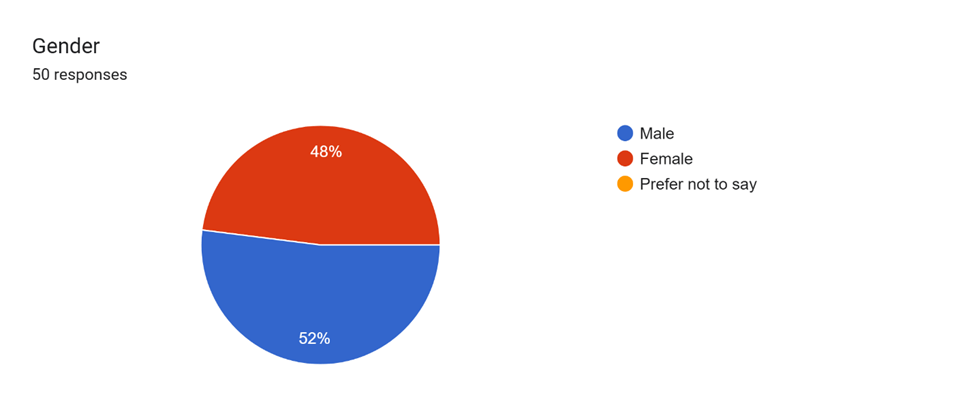

A Google survey was conducted, and data was captured from 50 participants (Appendix A). The survey was sent out to people in North Carolina and Virginia. The questions asked are in Appendix A. The data, including demographics, age, sex, dietary habits etc. were then analyzed using excel spreadsheet.

Results

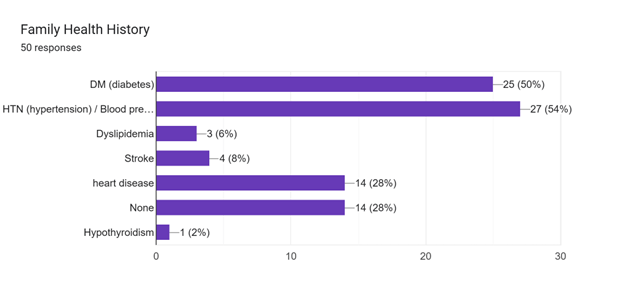

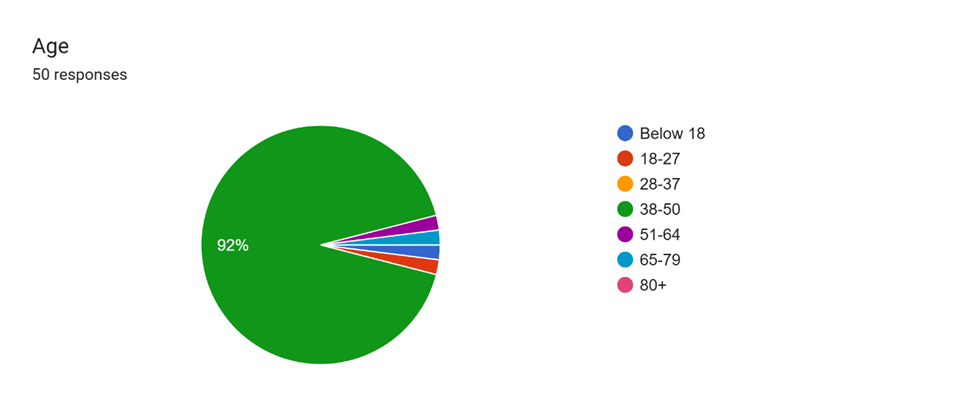

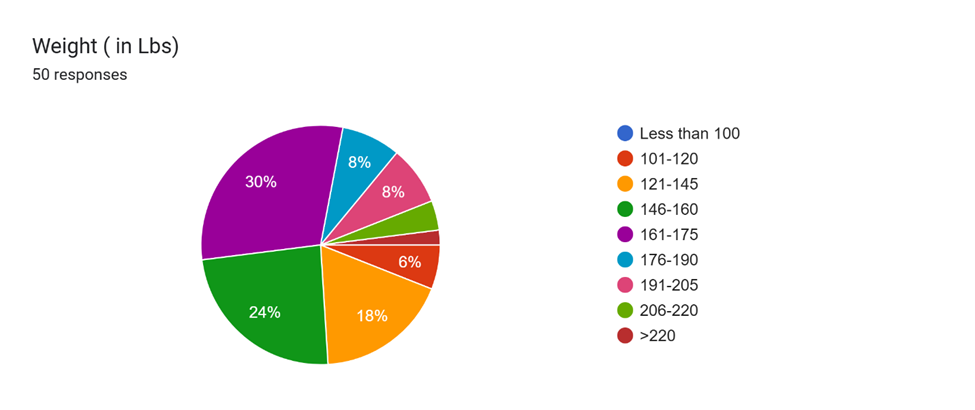

The survey results revealed health patterns among South Asians which can be associated with Diabetes and Pre Diabetes. Of the 50% of respondents, 42% exhibited elevated cholesterol levels, with males having a higher prevalence than females. In contrast, when looking at HDL levels, 96% of women have greater than 40 HDL, and 88% of men have greater than 40 HDL, and any level 40 or above is desirable. Of all respondents, 23% have greater than 60 HDL, which is optimal for the prevention of heart disease. This indicates that South Asians in America live relatively healthy lifestyles. Healthy lifestyle in this context mean they follow a healthier diet , exercise regularly and promote mental, physical and social well-being. Respondents were asking about consumption of food habits like consumption of nuts, diet followed, consumption of Soda, fasting habbits, to determine if they follow a healthier lifestyle. BMI results indicated that while the majority (48%) were of healthy weight, defined with a BMI between 18.5 to 24.9, many were overweight (about 20%), particularly those who follow the Indian or Western Diets (Chart -1). Many respondents also had a family history of diabetes (50%) and Hypertension (54%). (Chart-2) While the majority have a healthy fasting glucose range from 90-100 mg/dL, (Chart-3) a lot of respondents were in the 5.7-6.4% range of Hba1c, which suggests a pre-diabetes . Other levels such as LDL, HDL, and Hemoglobin were relatively normal among respondents.

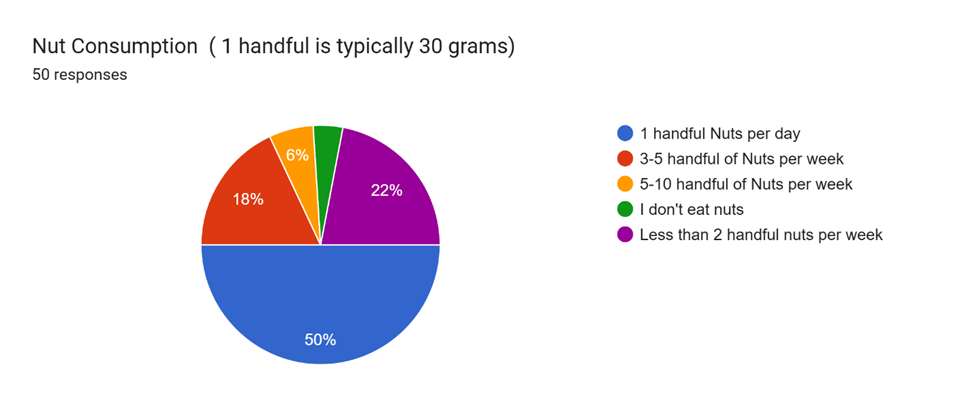

Lifestyle factors varied among respondents – while 48% got a healthy amount of exercise per week (1-2 hours or more), many were below the threshold (30%). Many respondents practice intermittent fasting a few times a year (16%) (Chart-4), but the results of the fasting remain unseen, most likely due to poor dietary choices. Nut intake was consistent among respondents, with 50% consuming about 30 grams of nuts per day, with almonds (85.7%), Cashews (77.1%), and Peanuts (70.8%) being the most popular.(Chart-5) Fruit intake was constant as well, with 78% of respondents consuming fruit regularly, eating about 1-2 cups of fruits daily (58.1%), and the most popular fruits being Apple (71.1%), Banana (77.1%), and Berries (65,3%). Regarding drinking consumption, 71% drank coffee, and 51.1% drank 1-2 cups of black coffee daily. 62% drink tea, and 43.8% of those who drink tea drink 1-2 cups of Chai (with sugar and milk). The majority of respondents drink alcohol, with 34% drinking 1-2 drinks a week, 20% drinking 2-5 cups a week, and 2% drinking 5-10 drinks a week.

Discussion

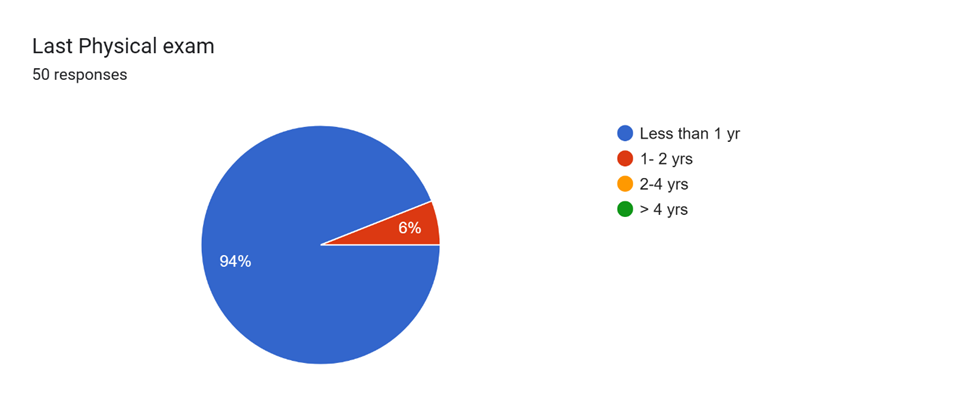

Overall, the results of this study provide a deep understanding of the health patterns and risk factors for prediabetes and diabetes within the Indian and Nepali community living NC and Virginia in the US. In the population studied , people of Indian and Nepali origin have a lower risk of DM which can be explained by diet and frequent exercise patterns, as well as regular visits to their primary care physicians (94% met primary care physicians within a year, 100% within 2 years). This can be supported in the overall sampled population through Cholesterol, Hemoglobin, LDL, and HDL levels for the majority being in a healthy range.

Indians and Nepali’s living in NC and Virginia have adapted to different lifestyle and health pattern where they are eating lot of healthier food and more balance diet . In South Asia diets are high in white rice and refined wheat such as Maida which can affect blood sugar, In the US, they switch to healthier alternatives like brown rice or quinoa instead. In addition, South Asians may shift away from using heavy oils and switch to healthier ones such as olive oil, air frying, and baking. When in the US, they also have more diverse diet options, most of them have a combination of different diets vs strictly following the Indian diet, this clearly reflects in the responses.

Interestingly the data also suggests there are significant reasons why diabetes is still prevalent. For starters, many people fall into the overweight and obese categories. In addition, many had elevated levels of Hba1c, which measures average blood sugar and is a good indicator for the diagnoses of diabetes and prediabetes, suggesting that diet plays a big role in diabetes prevalence. When looking more in-depth, the majority of those who were overweight ate an Indian Diet or a Western Diet. An Indian Diet is primarily composed of Carbohydrates such as Grains (lentils, roti, rice) and Starch Vegetables (potatoes) as well as Fats such as Ghee (clarified butter) and Milk. The Western Diet is also high in refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and sugary drinks which contribute to pre-diabetes and diabetes.

The overall lifestyle of respondents also significantly impacts the chances of diabetes. When looking at exercise from respondents, about 30% reported less than 1 hour of exercise per week, when the average amount of exercise for an adult should be 2.5 hours per week at minimum7onli. This lack of exercise can contribute to Insulin Resistance. Regular physical activity helps your body use insulin effectively, which lowers blood sugar levels, when you don’t exercise, the body struggles to move glucose from the bloodstream into the cells for energy. This can contribute to weight gain and increase the chances of developing diabetes. Alcohol consumption also seemed to be an issue, particularly among men. With 56% of respondents consuming alcohol, they are increasing their risk for hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, which are contributors to diabetes.

When comparing Gender discrepancies, women tended to be healthier than men. When looking at cholesterol levels, for example, women were more likely to have cholesterol levels under 200 mg/dL, while men exhibited higher rates of elevated cholesterol. In addition, more men are overweight (50% of men) than women (37.5% of females). When looking at trends in diet, however, both women and men who followed the Indian diet were more likely to be of a higher weight and cholesterol. With Lifestyle, men typically maintained a healthier lifestyle than women. For example, women who engaged in more than an hour of exercise per week (58.3%) were less than men who did the same (80.8%). Despite this, women were more likely to have higher HbA1c levels (58.8% had less than 5.7%) than men (38.5% had less than 5.7%).

One limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size of 50 people, which is not completely representative of the entire South Asian population in the USA. In addition, this study relies on self-reported data on diet, exercise, and health history which could result in response bias. This study does not account for any longitudinal trend changes in South Asian diets and health over time; these levels can continue to change. Finally, many respondents were from the age group 38-50 (90%), making the results less accurate to all age groups of South Asians in the USA.

Conclusion

This study highlights that people of Indian and Nepali origin who live in the US seem to have a healthier lifestyle resulting is comparatively lower risk of DM. This can be attributed to their dietary and exercise routines, as well as regular visits to primary care physicians for routine health check-ups and monitoring of vital signs. While family history shows higher chances of DM possible, through increased exercise, and a healthier diet, the chances of diabetes are reduced. Despite the study’s limitations such as a small sample size and reliance on self-reported data, the results provide valuable insight into health patterns within the Indian and Nepali community living in NC and Virginia. To further explore long-term trends and interventions, further experimental study and research with larger and more diverse patterns would need to be done.

Appendix A

- Country of Origin

- Years in USA

- Gender

- Age

- Weight

- Height

- BMI

- Personal Health History

- DM

- HTN

- Dyslipidemia

- Stroke

- Heart Disease

- Family Health History – DM, HTN, Dyslipidemia , Stroke, Health Disease

- Last Physical Exam

- Medication taken

- Medium to Rigorous exercise per week

- Smoking

- Alcohol Consumption

- Lab work

- Fasting Glocose level

- Hba1c

- HDL

- LDL

- Total choloestrol

- Hemoglobin

- Dietary Habits

- Type of Daily diet followed

- Weekend stable diet

- Weekday stable diet

- Any fasting followed

- Food Intake details

- Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages, like soda etc.

- Consumption of Coffee

- Consumption of Tea

- Consumption of Nuts

Appendix B

Results Charts and Graphs

References

- Gujral, Unjali P., and Alka M. Kanaya. “Epidemiology of Diabetes among South Asians in the United States: Lessons from the MASALA Study.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1495, no. 1, 1 July 2021, pp. 24–39, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33216378/, https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14530. [↩]

- Been, Latonya F., et al. “Variants in KCNQ1 Increase Type II Diabetes Susceptibility in South Asians: A Study of 3,120 Subjects from India and the US.” BMC Medical Genetics, vol. 12, 24 Jan 2011, p. 18, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.gov/21261977/, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2350-12-18 [↩]

- Bruin, Jennifer and Lahari Basu. “Why South Asians Are at Increased Risk for Diabetes: A Complex Interplay of Genetics, Diet, and History.” The Conversation, 14 Nov. 2022, theconversation.com/why-south-asians-are-at-increased-risk-for-diabetes-a-complex-interplay-of-genetics-diet-and-history-193613. [↩]

- Narayan, K. M. Venkat, and Alk M. Lanaya. “Why Are South Asians Prone to Type 2 Diabetes? A Hypothesis Based on Underexplored Pathways” Diabetologia, vol. 63, no. 6, 31 Mar. 2020, pp. 1103-1109, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05132-5. [↩]

- Gullapalli, Asha. “South Asian Diets.” The Johns Hopkins Patient Guide to Diabetes, 31 Jan. 2020, hopkinsdiabetesinfo.org/south-asian-diets. [↩]

- Kanaya, Alka M. “Diabetes in South Asians: Uncovering Novel Risk Factors with Longitudinal Epidemiologic Data: Kelly West Award Lecture 2023.” Diabetes Care, vol. 47, no. 1, 20 Dec. 2023, pp. 7–16, diabetesjournals.org/care/article/47/1/7/154008/Diabetes-in-South-Asians-Uncovering-Novel-Risk, https://doi.org/10.2337/dci23-0068. [↩]

- CDC. “Physical Activity for Adults: An Overview.” Physical Activity Basics, 20 Dec. 2023, www.cdc.gov/physical-activity-basics/guidelines/adults.html. [↩] [↩]

- Misra, A., et al. “Diabetes in South Asians.” Diabetic Medicine, vol. 31, no. 10, 16 Sept. 2014, pp. 1153–1162, https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12540. [↩]

- Mayo Clinic. “Arteriosclerosis / Atherosclerosis – Symptoms and Causes.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Clinic Staff, 20 Sept. 2024, www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arteriosclerosis-atherosclerosis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350569. [↩]

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. “Diabetes, Heart Disease, and Stroke | NIDDK.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Apr. 2021, www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/preventing-problems/heart-disease-stroke. [↩]