Abstract

The human neocortex is essential for advanced cognitive abilities like language, complex thought, and social interaction. This review summarizes the genetic and developmental factors that have driven the human neocortex to reach its current state and how rapidly emerging genetic engineering techniques promise to provide new insights into its evolutionary process. CRISPR-Cas9 allows for the precise manipulation of DNA, making it possible to examine how evolutionary changes may have contributed to the complexity of the human brain at the genetic level. When integrated with CRISPR, cerebral organoids have provided a novel system to observe how these genetic factors influence brain development across species. However, despite these advances, key questions remain about how these genetic aspects have interacted with environmental and social pressures to shape human cognitive evolution. Additionally, current models have limitations in fully replicating the complexity of the human brain. This review synthesizes the latest research on these technologies and outlines directions for future research. Using these technologies, scientists can gain a deeper understanding of how the human neocortex evolved to support the cognitive and social abilities that define humans.

Keywords: Cerebral organoids, CRISPR-Cas9, neocortex, evolution, gene editing, NOTCH2NL, ARHGAP11B, single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

Introduction

What genetic changes enabled the human brain to surpass that of other primates in complexity and function? Scientists believe that the answer may lie within the evolutionary adaptations of the neocortex, a region of the brain that processes sensory information and is in charge of complex behaviors. The neocortex is responsible for traits such as language, sensory reasoning, and complex thought, all of which help distinguish humans from other primates1. These unique cognitive abilities stem largely from evolutionary changes in the neocortex, with recent technological advancements such as Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-Cas9 (CRISPR-Cas9), a gene-editing tool using a guide RNA for precise DNA cleavage, and cerebral organoids (3D tissue models mimicking key brain features) having provided unprecedented opportunities for scientists to explore human neocortical evolution and study the genetic and developmental differences among primates.

The evolutionary development of the human neocortex is particularly fascinating due to its correlation with the cognitive abilities that underpin human social and intellectual complexity2. Studies comparing the structure of human and non-human primate brains suggest that the human neocortex attained greater complexity and functionality than other primates through a series of genetic and developmental adaptations3. Human cognitive capabilities emerged largely from the expansion and prolonged development of the neocortex4 in combination with environmental and social pressures. While certain features, such as sensory processing regions, are shared with other primates, humans also exhibit unique traits, including increased cellular diversity, prolonged cortical development, and higher neuronal density5.

Several human-specific genes have been identified as critical contributors to these neocortical advancements. ARHGAP11B and NOTCH2NL are some of the most studied. Due to their significance in human neocortical evolution, this review will primarily focus on these two human-specific genes, with others also mentioned. Outlining how these genes work, ARHGAP11B and NOTCH2NL are directly involved in neurogenesis and cortical expansion, processes critical for developing human cognitive abilities. In one study, ARHGAP11B (expressed in neural progenitors of the fetal human neocortex) promoted basal progenitor cell proliferation3, a mechanism essential for increasing cortical surface area and neuron count. Similarly, NOTCH2NL (part of the NOTCH pathway, which helps facilitate cell-to-cell communication in humans) enhanced neurogenesis in humans as found in a study by Fiddes and colleagues6‘7. Observing this, readers can see how subtle genetic changes can lead to dramatic differences in brain function. However, while these genes have been linked to cortical expansion, their exact roles in cortical organization and neuronal differentiation are not fully understood. Due to a myriad of ethical and technical limitations involved in the use of in vivo models, scientists have begun to opt for using in vitro models.

One in vitro model used to combat these challenges is cerebral organoids (CBOs), a promising application for studying human brain evolution. Introduced by Lancaster and colleagues8, these 3D, stem cell-derived models mimic many features of the developing human neocortex, including its layered architecture and neurogenesis. By creating a controlled environment for studying brain development, organoids have become key tools for investigating how specific genes influence the neocortex. An added benefit of CBOs is that they are not limited to humans; they can model various species, allowing cross-species comparison8. Despite these advancements, CBOs face limitations, including the absence of interaction with other bodily systems and a lack of long-term development9.

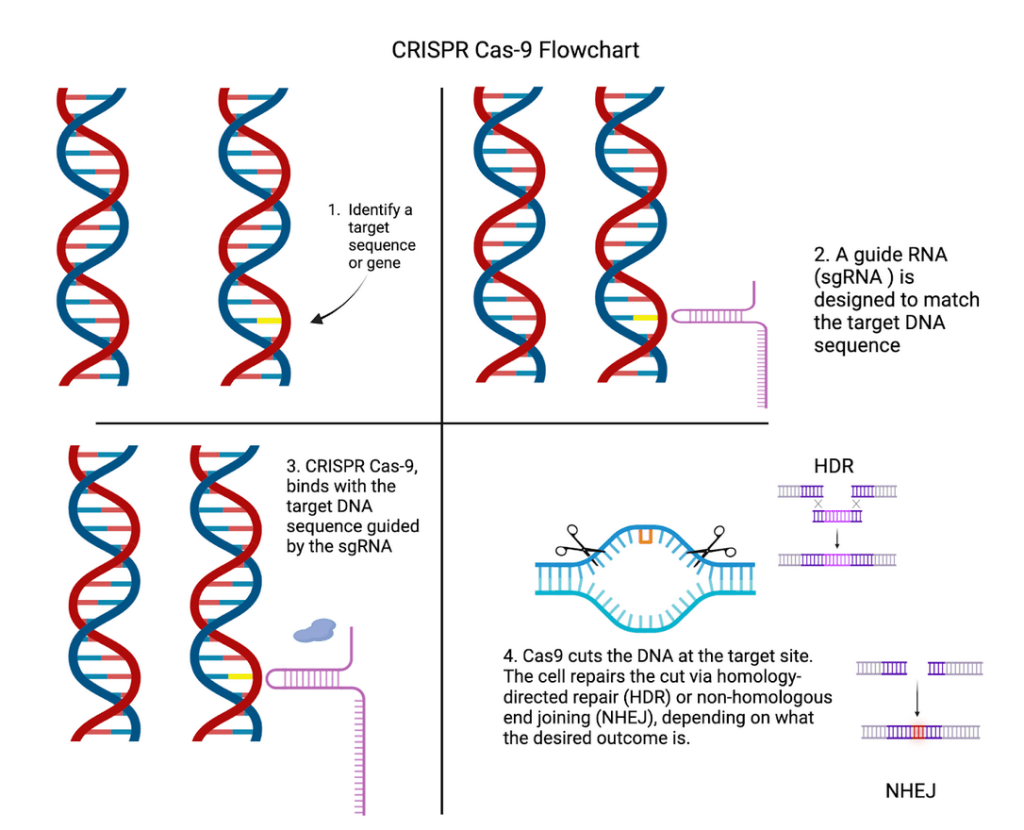

While CBOs provide a valuable platform for studying neocortical development, their capabilities are enhanced significantly when using CRISPR-Cas9. Doudna and Charpentier emphasize CRISPR’s groundbreaking potential for genome editing10; allowing for targeted manipulation of genes with unprecedented specificity. Building on CRISPR’s general capabilities, CRISPR also has several unique applications in neuroscience, with its cleaving mechanism allowing researchers to develop Alzheimer’s treatments all the way to mapping human evolution11. Figure 1 shows the key steps involved in the CRISPR-Cas9 process, from identifying the target gene to repairing the cut DNA.

When applied to CBOs, key genes that play a role in brain development and function can be investigated, thus helping to better understand what effect genetic contributions had on neocortical-developmental differences amongst primates.

The unmatched precision of CRISPR for gene-editing allows scientists to modify or knock out specific genes within organoids, revealing their roles in neocortical evolution. For example, Fiddes’s study where he found that introducing NOTCH2NL in organoids led to increased neuronal production, would not have been possible without CRISPR’s precise mechanism6. Similarly, mutations introduced in ARHGAP11B have recently only been possible due to the conception of CRISPR, giving scientists clarity on how this gene drives cortical expansion. Moreover, CRISPR enables the investigation of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), which are variations at a single DNA base pair that can influence gene expression and protein function12.

Depending on where they occur in the genome, SNPs can influence human traits and evolution in different ways. When located within coding regions of a gene, SNPs can alter the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein, potentially changing its structure or function. In contrast, SNPs in non-coding regulatory elements (segments that only control gene activity), such as promoters, enhancers, and untranslated regions, do not directly alter protein structure but can modify when, where, and how much a gene is expressed.

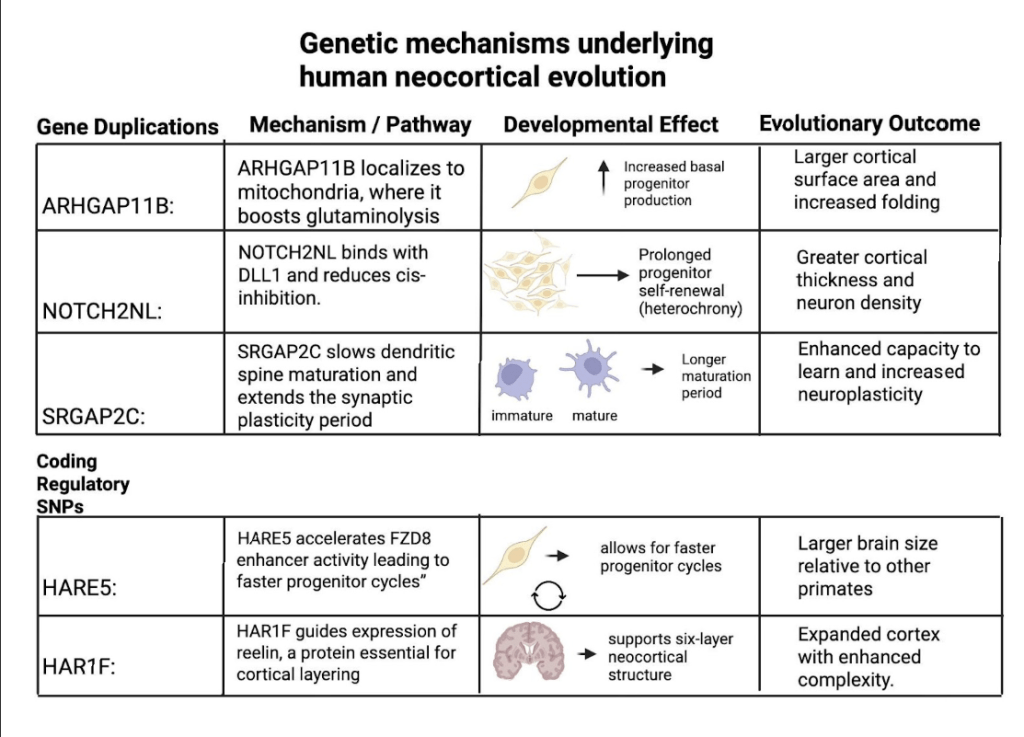

One such non-coding regulatory element is HARE5 ( a stretch of DNA especially accelerated in humans), an enhancer located near the frizzled gene FZD8, which regulates brain growth during development. In 2015, Boyd and colleagues showed that the human version of HARE5 drives earlier and stronger FZD8 expression than its chimpanzee counterpart13. Another one of these human-accelerated regions, HAR1F (a long non-coding RNA expressed during cortical development), has been implicated in neuron layering and cortical expansion, further illustrating the key role of non-coding elements in human brain evolution14. Because HARE5 and HAR1F both contain SNPs that alter their regulatory activity and due to CRISPR’s amenability to SNPs, scientists are able to precisely introduce or revert SNP gene variants between humans and primates using CRISPR techniques, enabling direct tests of genetic effects on neurodevelopment. Examining these timing and expression shifts during neurodevelopment exemplifies heterochrony(evolutionary changes in the timing or rate of an organism’s development relative to its ancestor) that have been central to human neocortical expansion and complexity14. However, although SNPs in small non-coding elements can only subtly modulate neurodevelopmental gene activity, large-scale changes like the emergence of human-specific genes can introduce entirely new functional capacities.

Closely linked to SNPs is a method introduced by Komor and colleagues, base editing, a CRISPR-based method that enables the precise conversion of individual DNA without inducing double-strand breaks; ideal for helping researchers understand how minor genetic variations influence uniquely human traits15.The promise of SNPs and base editing highlights the potential of CRISPR and organoids to uncover the genetic mechanisms behind human brain evolution.

Despite these advances, several questions remain. It is key to further progress to find beyond human-specific genes, what other genetic, environmental, and social factors contributed to the structural and functional complexity of the human neocortex. Moreover, finding out how environmental pressures and social behaviors interact with these genetic changes to shape evolutionary outcomes is necessary. Furthermore, understanding the extent to which SNPs can explain subtle variations in connectivity and development between humans and other primates will be vital. Addressing these questions will require integrating insights from genetic studies, organoid models, and evolutionary neuroscience.

This review will synthesize current research on neocortical evolution, with a focus on how the application of CRISPR to 3-dimensional tissue models such as CBOs can be used to explore how human-specific genes function. The present work will also highlight areas for future research, such as identifying and understanding the key mechanisms and genes that underlie the unique structure of the human neocortex. By integrating studies on key evolutionary genes, CBOs, and advanced gene-editing techniques such as CRISPR, this paper will highlight the evolutionary mechanisms that may have shaped the human neocortex. Ultimately, this literature review holds potential for revealing how human-specific genes and developmental processes contributed to the evolution of the brain.

Methods

This study is a literature review synthesizing current knowledge on human neocortical evolution, cerebral organoid modeling, and CRISPR-based genetic analysis. This review was conducted by searching an online database of journal articles for relevant material spanning from 2009 to 2021 and analyzing them accordingly within the scope of CRISPR-Cas9 and CBOs. While researching, multiple academic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, were searched using combinations of topics such as human neocortical evolution, cerebral organoids, human-specific genes, CRISPR, and comparative primate brain development. Key details were collated using reference management software (Mendeley, v2.128) and Microsoft Excel. Analysis was done based on certain inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for papers included the number of citations, Journal Impact Factor (JIF), whether or not the study was peer-reviewed, correspondence with the key ideas of the review: genetic mechanisms underlying neocortical evolution, CRISPR, or CBOs, and finally, whether the papers were available in English with full-text access. This review looked for agreements between papers and critically evaluated contradictions in order to validate findings. Exclusion criteria included articles lacking clear methodological descriptions and review papers that omitted original findings. Key data points extracted from the selected studies included authors and publication year, study objectives pertaining to neocortical development, and findings on the potential role of CRISPR-Cas9 and models like CBOs in mapping human evolution. Forward/backward citation tracking was used to identify additional relevant studies not retrieved in the initial search. When multiple papers covered similar material, the most recent and comprehensive study was prioritized. This review did not include in vivo or lab data; it was limited by the availability of open-access articles.

Literature Review

General Background on the Development of the Neocortex

The neocortex, a key structure stemming from mammalian evolution, is central to the functions that distinguish humans from other primates. This six-layered brain structure is composed of specialized regions that process sensory information, direct motor commands, and enable higher cognitive functions such as reasoning and language1. Understanding its evolutionary expansion and increased complexity is key to comprehending the emergence of human-specific qualities.

The neocortex originates from the neural tube, the structure that goes on to form the brain and spinal cord in an embryo by producing radial glial cells (RGCs). RGCs are progenitors (cells that divide and differentiate). A subset of RGCs, basal progenitors, are especially present in humans, contributing to neuronal proliferation and the expansion of cortical surface area3 This expanded cortical surface area leads to dense neuronal networks that support the human brain’s higher cognitive capabilities compared to other primates.

Differences Between Human and Non-Human Primate Neocortices

Evolutionary studies have shown that although non-human primates also possess a well-developed neocortex, human neocortical expansion is unparalleled in terms of complexity. Studies comparing brain size and neuron counts show that humans have approximately 16 billion cortical neurons, compared to ~ 6 billion in chimpanzees2. How are humans able to facilitate this increased density?

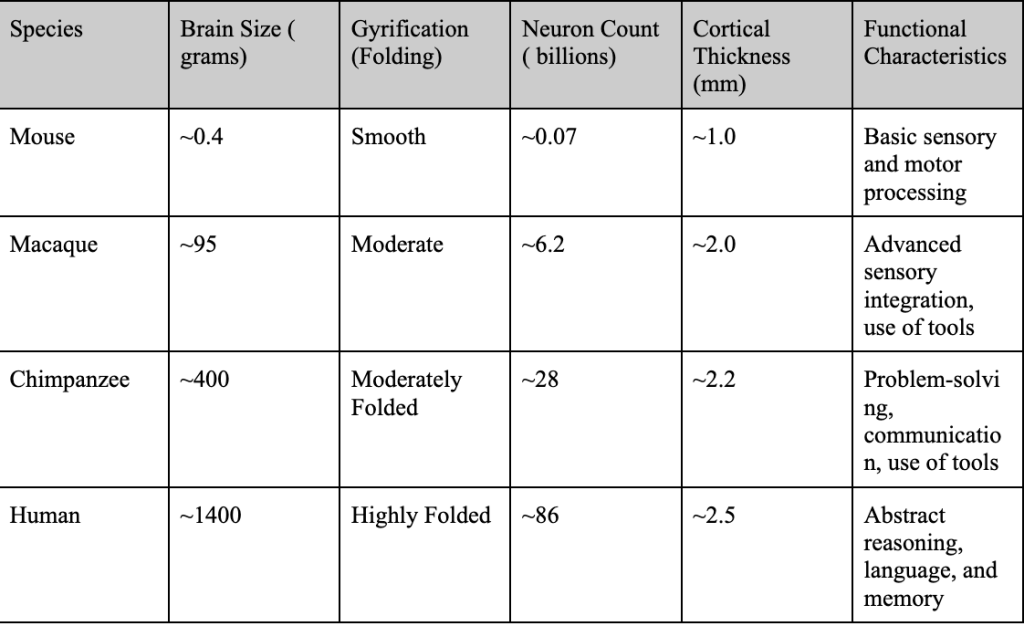

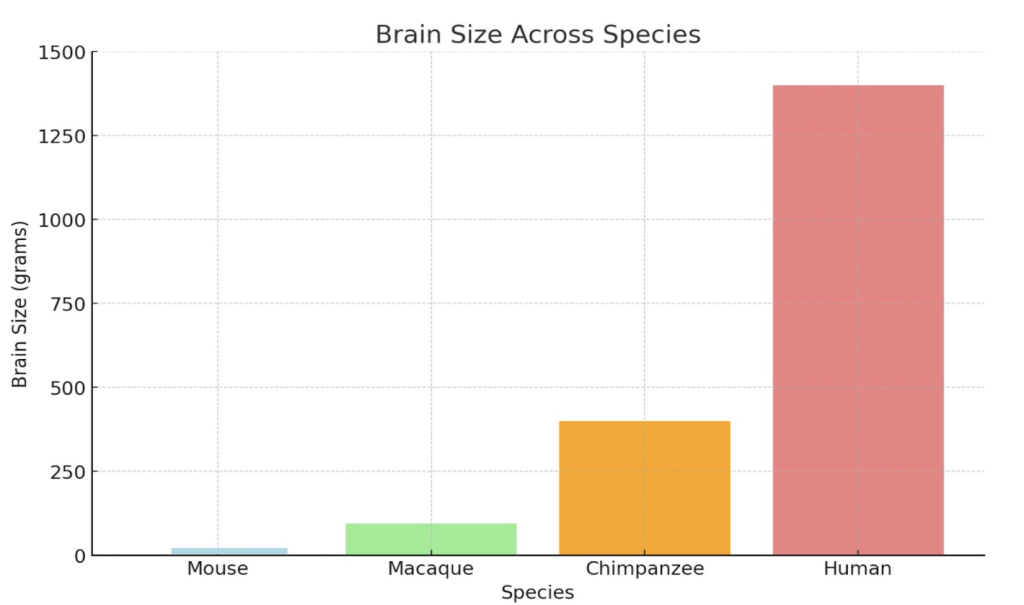

Structurally, the human neocortex is larger, more complex, and more heavily folded than other primates, with a higher surface area relative to brain volume. This increased folding is due to a process known as gyrification, which allows for more neurons to be fitted into a smaller place (more neuronal density), enhancing cognitive power and information processing2. Figure 2 compares the brain structures of various species, highlighting the traits that led to the increased complexity of the human brain.

Figure 2 | Comparative Cognitive and Structural Traits Across Species – (A) Table highlighting brain size (grams), gyrification (folding), neuron count (billions), cortical thickness (mm), and functional characteristics of mice, macaques, chimpanzees, and humans. (B) Cross-sectional image comparing the brain structures of a mouse, chimpanzee, and human, scaled to 10 cm. Adapted from DeFelipe16. (C) Bar graph illustrating brain size (grams) across mice, macaques, chimpanzees, and humans, emphasizing the significant increase in human brain complexity.

Observing Figure 2, humans have increased neuronal density and output compared to their primate counterparts. This is due to a delayed neuronal proliferation period during development4. The prolonged cortical development humans experience extends the period for synaptic refinement and complex neural circuit formation, leading to higher neuronal density. The higher neuronal output and density also allows for increased connectivity amongst neurons and improved synaptic pruning ( usage-dependent synapse loss ). In addition, delayed maturation and cortical folding allow for the formation of more complex circuits and the fostering of advanced abilities such as abstract reasoning and language4. These traits, combined with structural features, set humans apart from non-human primates both structurally and functionally. Figure 3 quantifies structural differences, comparing neuronal density and cortical surface area across species.

These structural traits imply not only more neurons but also the need for early support structures that coordinate and support inter-neuronal communication during development. One such structure is the subplate (a fetal layer that is largely expanded in primates, especially humans)4. During the middle of the gestation period (when humans are in the womb), the subplate functions as a temporary relay and information hub: thalamo-cortical and early cortico-cortical axons pause and synapse within the subplate before entering the cortical plate4‘8, while subplate neurons generate electrical activity and molecular cues that refine brain topography and establish routes between areas17. The greater thickness and persistence of the human subplate relative to non-human primates likely support our prolonged developmental timeline and expanded cortical networks4.

Table 2 in the section (CBOs in Cross-Species Modeling) synthesizes these species-specific features and illustrates how well organoids recapitulate them.

Genetic and Cellular Aspects of Human Neocortical Evolution

Understanding the genetic groundwork for the evolutionary leap from other primates to humans has become a key question in neuroscience. Human-specific genes such as NOTCH2NL and ARHGAP11B have been shown to aid in enhancing neurogenesis and increasing neocortical complexity367. These genes aid processes such as basal progenitor amplification and extend the period of progenitor maintenance, illustrating how subtle genetic improvements can yield major structural and functional differences across species.

Mechanistically speaking, both ARHGAP11B and NOTCH2NL function in different ways. What ARHGAP11B does first is localize to mitochondria, where it boosts glutaminolysis (a process that converts glutamine into energy). Allowing for glutaminolysis makes it so that basal progenitor cells can divide more times than they normally would, and produce more neurons3. In contrast, NOTCH2NL fine-tunes the Notch signaling pathway, a system that decides whether progenitors keep dividing (giving them more time to mature) or just become neurons. Normally, Delta-like 1 (DLL1) ligands on the same cell can block their own Notch receptors (a process called cis-inhibition), but NOTCH2NL interferes with this block (reducing cis-inhibition), which allows neighboring cells’ DLL1 ligands to activate Notch receptors instead (called trans-activation). This makes it so progenitors delay their differentiation, and ultimately gives rise to a greater number of neurons during cortical development6‘7.

Human-specific genes such as ARHGAP11B and NOTCH2NL are so important that when knocked out, severe neurological implications can occur. For example, when ARHGAP11B is knocked out in human organoids, an early neurogenic switch is triggered, which creates a microcephaly-like phenotype17. Additionally, copy-number variations or expression imbalances of NOTCH2NL genes (where an abnormal number of gene copies alters gene expression) within the 1q21.1 chromosome (a region prone to microdeletions or microduplications) are linked to several neurodevelopmental outcomes, including autism spectrum disorders as well as microcephaly in humans6‘7.The fact that these disorders form when these genes are absent underscores just how important these human-specific genes are in ensuring normal cortical size and function.

However, human evolution is not limited to just NOTCH2NL and ARHGAP11B. Other key human-specific genes include SRGAP2, which enhances neuronal plasticity by delaying neuron maturation18, FOXP2, which may have contributed to speech and language advantages in humans19, and TBC1D3, which is linked to neuronal progenitor expansion20. Collectively, these genetic adaptations reveal some of the possible drivers of human neocortical evolution.

Building on this, these evolutionary adaptations of the human neocortex are linked to behaviors that define human uniqueness, such as advanced problem-solving and high-level language. As previously mentioned, genes attributed to human evolution, such as SRGAP2 and NOTCH2NL, allow for a prolonged period of neuronal development6‘7‘17. However, there are variations of these genes. For example, SRGAP2 has a variant called SRGAP2C, which is a human-specific truncated copy of SRGAP2. It interferes with the full-length SRGAP2 protein and slows dendritic spine maturation, which extends the period of synaptic plasticity in developing neurons18. The heightened connectivity between neural networks and delayed development caused by these genes aids in the development of advanced behaviors, such as multitasking, creative thinking, high-level language, abstract reasoning, increased learning and adaptability, all of which are not found in other primates2. Knowing how these genes correlate with behaviors that are underdeveloped in non-human primates, readers can observe how genetics played a role in human evolution. This link between genetic changes and advanced human behaviors highlights how important genetics may be to the evolution of the neocortex and differentiating human thinking and social abilities from other evolutionary ancestors.

However, it is important to note that these human-specific genes did not originate from SNP changes but rather from segmental gene duplications that created novel paralogs ( pairs of related genes created through duplication events) with distinct functions. For example, ARHGAP11B arose from a partial duplication of ARHGAP11A that introduced a novel protein sequence boosting basal progenitor proliferation3. Similarly, NOTCH2NL emerged from duplications of NOTCH2(a receptor protein from the NOTCH pathway) that amplify Notch signaling and prolong cortical stem-cell renewal6‘7. SRGAP2C, in contrast, resulted from a truncated duplication of SRGAP2 that interferes with its parental SRGAP2 protein18. While duplications were the ones that created these unique genes, SNPs in regulatory elements such as HARE5 near FZD8 or HAR1F still play a role in fine-tuning the timing and expression of the processes of neurodevelopment. Here is Figure 4 to integrate both gene duplications and regulatory elements into a cohesive table, highlighting their mechanisms, developmental effects, and evolutionary outcomes.

Beyond changes to the genes themselves, epigenetic and regulatory factors likely boost the impact of these genes. Small changes in regulatory DNA (enhancers, human-accelerated regions) and in epigenetic marks (DNA methylation, histone states), plus non-coding RNAs, can change when and how strongly key pathways (Notch, WNT, FGF, BMP) are turned on21. In humans, this too tends to keep neuronal progenitors dividing longer and slows down heterochrony22. Environmental cues (e.g., metabolic or oxygen state) act through the same regulatory layers. However, regardless of their different individual functions, these human-specific genes converge in their overall outcome, which is to prolong neocortical development and to increase neuronal output in the developing cortex23.

Still, despite all of the unique genetic, structural, and developmental differences between humans and other primates, there are several unique cellular features of the human neocortex. The discovery of human-specific cell types highlights some of these features. One of these cell types is rosehip neurons, a neuron found exclusively in humans24. These neurons have a distinct shape that forms specific synaptic connections found only in humans. They are thought to play a role in fine-tuning circuits in the neocortex and modulating neural activity. The absence of these neurons in other primates may suggest that these cells evolved to support uniquely human brain functions. Additionally, human neocortical development is supported by unique human-specific progenitor types. One of these cells is Outer radial glial cells (oRGs), a subset of basal progenitors that are more present in humans than in non-human primates. These cells play a crucial role in expanding cortical surface area and generating neurons and facilitating brain folding. They are found especially in the outer subventricular zone (oSVZ), a region that expanded further in humans than in their primate counterparts. The presence of these cell types shows the drastic cognitive differences between humans and other primates. Despite these insights, our understanding of neocortical differences in primates is constrained by limitations in existing research models.

Current Limitations of Models

Traditional models for studying brain development and evolution, while useful, face significant limitations. Mouse models, although widely used in genetic experiments for their ease of use, fail to replicate key aspects of human brain development. Structurally, the mouse neocortex exhibits lissencephaly, meaning it lacks the folding (structures known as gyri and sulci) that increases cortical surface area in human brains, likely contributing to lower cognitive ability. Furthermore, the mouse brain lacks an expanded oSVZ, a feature essential for human cortical expansion25. These structural differences between mice and humans during development and in gene expression limit the application of neocortical findings in mice to humans.

2D cell cultures and induced neurons provide a more human-specific perspective to map this, but remain overly reductive. These models lack the 3D architecture and the cellular diversity of the neocortex, reducing their capability to simulate human-developmental processes accurately8.

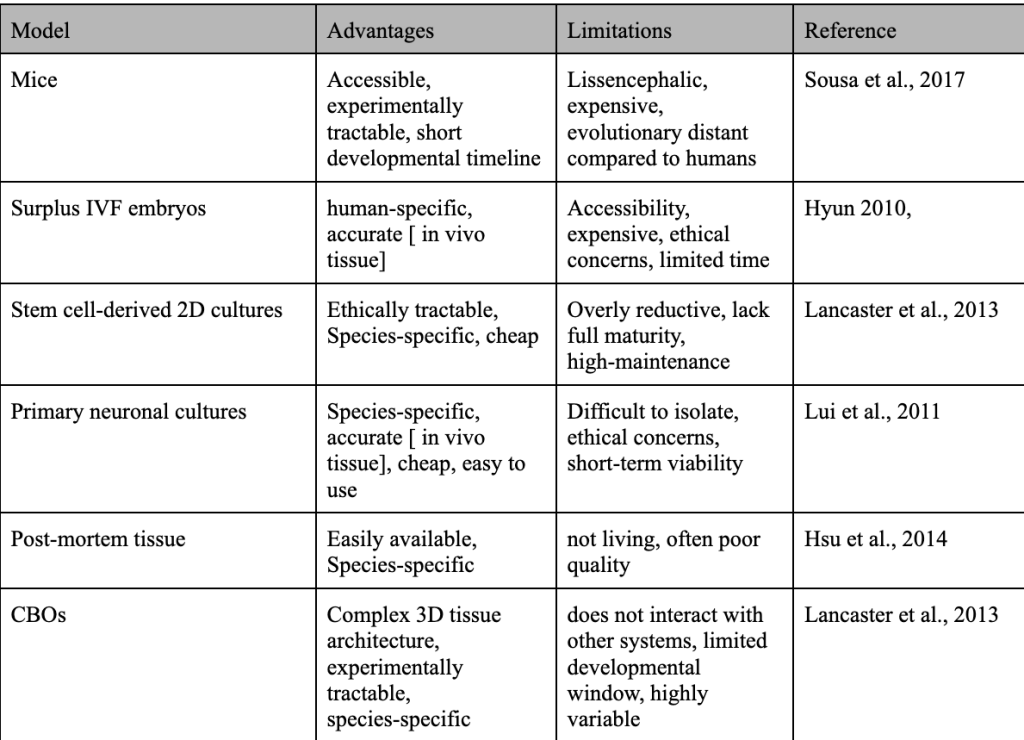

Ethical and logistical challenges further restrict access to in vivo human models. Studies involving human fetal tissue are limited by their availability and ethical concerns regarding obtaining them and consent issues. Models like surplus IVF embryos, on the other hand, raise questions about accessibility and morality; when do scientists classify them as living? These constraints shed light on the difficulties of exploring and modeling human-specific traits and neocortical development12‘26. Table 2 lists differences between various commonly used models for modeling human brains.

As a result, there is a pressing need for models that bridge these gaps. CBOs have emerged as a promising model to address these issues.

CBOs in Modeling Human Brain Development

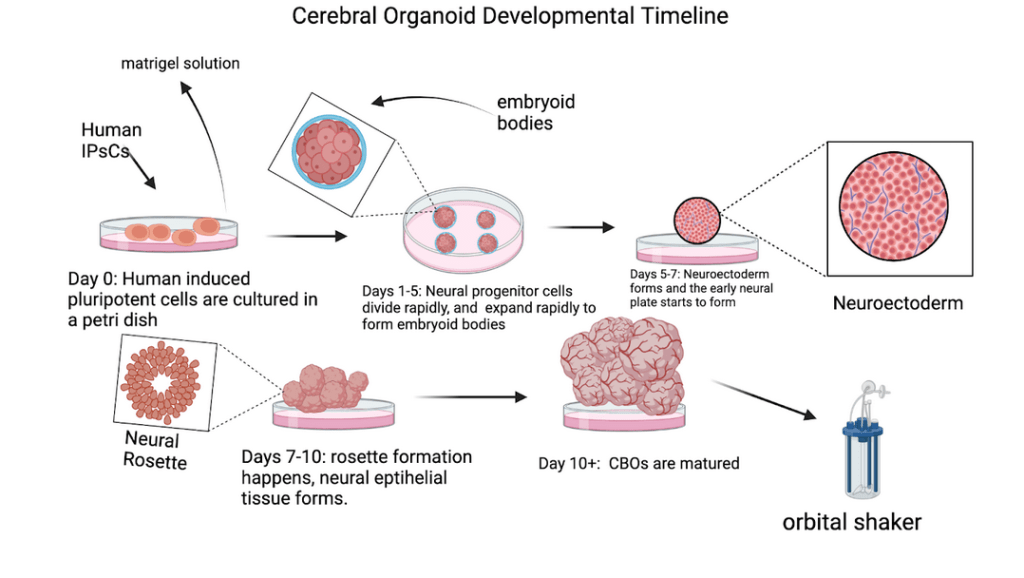

CBOs are stem cell-derived 3D models that replicate aspects of early brain development. Introduced by Lancaster and colleagues8‘ these organoids are grown in a 3D culture system, allowing them to form structures resembling the cortical plates and ventricular zones of the developing human brain. Figure 5 outlines the timeline of cerebral organoid development, from initial stem cell cultures to mature organoids. This innovation enables researchers to study and model human brain development and evolutionary traits with unprecedented accuracy.

Comparative organoid studies also provide correspondence to the many unique aspects that human organoids exhibit. They have helped support many distinct qualities that differentiate humans from other species: a prolonged progenitor cell cycle and extended neurogenic period, producing more upper-layer neurons3‘27; delayed neuronal maturation and synaptogenesis, yielding a longer “immature” window for cells to develop1‘18‘28; and novel transcriptional profiles (snapshots of RNA at a given point) of human-specific genes (e.g., NOTCH2NL, ARHGAP11B, SRGAP2) as well as regulatory RNAs3‘6‘7‘18. CBO studies also support metabolic and epigenetic states consistent with prolonged stem cell renewal21‘27; and subtle differences in cell-type proportions and timing, such as later development of the brain and spine27‘29. These evolutionary differences, which increased neuron number and circuit complexity in the human neocortex, would have been impossible to realize without CBOs22‘25.

The versatility of CBOs has been demonstrated across various fields. They have been used to model neurodevelopmental disorders, such as microcephaly, and investigate the effects of diseases such as the Zika virus infection7. In the context of neocortical evolution, CBOs have enabled studies on human-specific genes, offering insights into how genetic changes drive structural and functional differences.

Additionally, CBOs address many limitations of traditional models. Their unguided developmental program allows for a wide array of cells to be present in them, including neurons, glial cells, and progenitor subtypes, while mimicking the layered 3D organization of neocortical tissue8.

Limitations of CBOs

Despite their promise, CBOs face several limitations that restrict their ability to fully model human neocortical development. While CBOs have demonstrated the ability to generate oscillatory electrical activity (synchronized rhythmic patterns produced by neurons), these signals do not reflect the complexity of mature brain networks. Instead, their activity more closely resembles the rather uncoordinated patterns observed in fetal brain development28‘30. CBOs notably lack postnatal features critical for cortical maturation, including synaptic development, neuroplasticity, myelination, and the formation of proper axonal projections8‘23.

Another major issue of organoids is their lack of vascularization and a blood-brain barrier, which restricts oxygen and makes it difficult for nutrients to diffuse to the interior regions of the organoid. This can lead to cell death and low-oxygen conditions, negatively impacting neurodevelopmental outcomes31. Additionally, organoids lack a functional immune system, making it difficult to partake in the homeostatic regulation of the developing brain. Moreover, CBOs are devoid of key cell types, namely microglia, which are necessary for processes such as synaptic pruning31.

CBOs also fail to replicate inter-regional connectivity. While organoids can model specific brain regions in isolation, they lack the long-range connections seen in vivo unless combined into co-culture systems called assembloids, which fuse regions like the forebrain and midbrain23‘32. Moreover, organoids typically do not progress beyond early fetal developmental stages, as current protocols halt further progression. This limits their capacity to model later events such as synaptic integration, circuit refinement, and postnatal myelination29‘32.

Another important limitation involves the disproportionate representation of glial cells. Astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, which are critical for neurodevelopment, especially in astrocyte-neuron coupling and myelination, are often present in non-physiological ratios, affecting cellular interactions and cortical maturation32.

Furthermore, CBOs poorly recapitulate temporal dynamics and cortical arealization, both of which are key features of neocortical evolution. In vivo, the spatial and temporal development of cortical regions is guided by morphogen gradients, particularly those involving FGF8, WNT, and BMP signaling pathways13‘33. These cues help with molecular patterning, allowing them to guide cerebral cortex development. However, these gradients are not well-reproduced in standard organoid systems22.

CBOs in Cross-Species Modeling

Despite these limitations, organoids remain a powerful system for modeling early developmental stages of the neocortex34. A key advantage of CBOs is their utility in cross-species modeling. Kanton et al. demonstrated how organoids can reveal species-specific developmental differences, such as the prolonged neurogenesis and increased upper-layer neuron production unique to humans, by comparing human and non-human primate CBOs27.

Building on the species differences outlined thus far, including the expanded human subplate and human-specific genes, this review next compares how organoids model these developmental features across lineages. Table 3 provides a concise cross-species summary of the cortical development of humans, non-human primates, and mice, highlighting where organoids are able to reproduce early corticogenesis and where they fall short.

| Feature | Humans | Non-Human Primates | Mice | CBOs | Sources |

| Neurogenesis Duration | ~100 days | ~60–80 days | ~7–10 days | Modeled up to ~70–90 days | Kanton et al., 2019; Molnár et al., 2019 |

| Progenitor Types | aRG (apical radial glia – stem cells in the ventricular zone), oRGs, bIP (basal intermediate progenitors – transit amplifiers that generate neurons) | aRG, fewer oRGs | Mostly aRG, bIP | aRG, oRG (underrepresented), bIP | Espinós et al., 2022 |

| Neuronal Layering | 6 layers, distinct | 6 layers, thinner | 6 layers, compact | Partial lamination, often disorganized | Lancaster et al., 2013 |

| Cell Composition | Neurons, astrocytes (support synapses), oligodendrocytes (myelinate axons), microglia (immune cells) | Similar to humans | Low astrocyte:neuron ratio | Neurons predominant; astrocytes/oligos delayed; no microglia | Molnár et al., 2019 |

| Connectivity | Extensive long-range connections | Moderate | Minimal | Absent (except in assembloids) | Pollen et al., 2019 |

| Subplate Zone | Prominent, long-lasting (temporary relay for wiring) | Present, transient | Thin, transient | Poorly defined or absent | Molnár et al., 2019 |

| Key Pathways Active | WNT, BMP, FGF8, SHH, NOTCH | WNT, SHH, NOTCH | WNT, SHH, EGF | WNT, BMP (limited patterning) | Espinós et al., 2022 |

| Migration Dynamics | Extensive radial (via radial glia) and tangential (interneuron migration) | Similar | Mostly radial | Radial, incomplete; no interneuron migration | Pollen et al., 2019 |

| Synaptic Maturity | Postnatal pruning, myelination | Less prolonged | Early maturation | Fetal-like synapses; limited activity | Kanton et al., 2019 |

| Epigenetic/Transcriptomic Profile | HARs, lncRNAs, microRNAs | Conserved enhancers; fewer HARs | Distinct enhancers | Partial match to early human cortex | Kanton et al., 2019 |

Looking at the table, CBOs more accurately replicate early human neurodevelopment compared to other models like mouse models or 2D cultures29. This accuracy is due to them being derived from stem cells. Being stem-cell derived also allows them to model key human-specific features (such as prolonged neurogenesis and elevated neuronal output), making them especially valuable for evolutionary studies.

Furthermore, they are highly scalable (able to be generated in large batches), ensuring consistency in experiment results. Also, being a scalable 3D system and having the ability to mimic human developmental characteristics leads to them being highly amenable to gene editing. CBOs are an ideal platform for integrating human-specific genes using gene-editing technology. By combining both technologies, researchers can bridge gaps in our understanding of neocortical evolution and uncover the mechanisms that underlie human brain evolution.

Gene Editing in Evolutionary Neuroscience

Gene editing, particularly through CRISPR-Cas9, has revolutionized evolutionary neuroscience. CRISPR-Cas9 uses guide RNAs to target specific DNA sequences, enabling precise gene editing with unmatched efficiency10. This technology has proven to be invaluable for investigating human-specific genes and finding their targeted roles in brain development.

CRISPR’s precision extends to base editing, in which single-nucleotide bases are modified without causing double-strand breaks. This approach enables the study of SNPs, which may have contributed to uniquely human traits16. Previous applications of CRISPR in evolutionary research include investigating Neanderthal alleles and reconstructing ancestral genetic changes, showcasing its potential to uncover the genetic basis of human brain evolution24. And although CRISPR is an effective technology for mapping human neocortical development, the ethical complexities of editing the human genome, as well as problems like off-target editing, remain as barriers to its broader application12‘35.

Despite these challenges, when integrated with CBOs, CRISPR has enabled experiments that were previously impossible. The integration of the two technologies allows researchers to manipulate human-specific genes in a biologically relevant 3D context. As demonstrated in the work of Florio et al. and Fiddes et al.3‘6, knocking out human-specific genes in CBOs using CRISPR reveals how subtle genetic improvements can influence neocortical development. Together, these technologies provide a powerful platform for scientists to look into the genetic mechanisms underlying human brain evolution.

Discussion

The data presented in this study highlights several unique features of human brain development and provides insights into human neocortical evolution. Humans are born with a neocortex that is disproportionately thicker and more neuron-dense compared to that of other primates3‘5. This finding suggests that it was evolutionary and genetic changes that helped accelerate cortical growth in the womb, providing for advanced cognitive abilities early in life. At the same time, the human brain’s prolonged development after birth and heavy reliance on social learning in childhood to refine its circuits indicate that cultural and environmental factors are strongly tied to cortical development22‘25. Together, these observations imply that both innate genetic changes and extended developmental plasticity contributed to the exceptional capabilities of the human brain. In addition, these features are consistent with extended neurogenic timing (heterochrony) and expanded oRG cell populations described in primate corticogenesis22.

Understanding the mechanistic basis of these human-specific features, however, is challenging due to limitations of current experimental models. Rodent brains, for example, lack many of the developmental programs and unique genes of human neocortical expansion. Ethical constraints have also made it difficult to engage in extensive experimentation on primates. Additionally, although CBOS show lots of promise to model human neural development and provide a form of genuine human neural tissue for experiments, they have significant shortcomings. CBOs typically resemble an early fetal brain and cannot develop the later-stage features (such as complex neuronal circuits or glial maturation) that arise in vivo. These limitations mean that current organoid models capture only a small portion of human brain development, which in turn limits the conclusions scientists can draw about uniquely human traits.

Despite these experimental challenges, through comparative developmental research, multiple human-specific genes such as ARHGAP11B and NOTCH2NL have been identified as key drivers of our species’ cortical expansion and increased neuron production3‘6‘7.These genes illustrate how genetic changes can have large effects on brain growth.

In addition to increasing neuron number, genetic human evolution also modified how neurons form connections and circuits. For example, the SRGAP2C variant of SRGAP2 altered how cortical neurons mature by extending the period during which neurons can form and adjust connections, which may contribute to humans’ superior learning capacity and cognitive flexibility. These uniquely human genes (such as ARHGAP11B, NOTCH2NL, SRGAP2C, and others) provide a molecular basis for the dramatic increase in cortical size and complexity seen in our species. They suggest that relatively small genomic changes (gene duplications or modifications unique to humans) had profound effects on brain development, helping to create the structural foundation for human intelligence.

Together, gene duplications (ARHGAP11B, NOTCH2NL, SRGAP2C) and fine-tuned regulatory changes (SNPs in enhancers like HARE5 and HAR1F) illustrate how different scales of genetic modification contributed to human brain evolution. Understanding these mechanisms not only clarifies our evolutionary past but also highlights the promise and limitations of current tools like CRISPR and cerebral organoids in modeling the unique complexity of humans.

Future Recommendations

Looking ahead, although CRISPR-Cas9 and CBOs have provided unprecedented tools for exploring neocortical evolution, developing a truly comprehensive understanding of how the human brain diverged from that of non-human primates requires a combination of several techniques to be used. This paper proposes the adoption of a multi-faceted strategy to map human brain evolution that combines comparative organoid modeling and studies on gene–environment interaction. Furthermore, using machine learning analysis to identify and test the mechanisms that underlie our unique human brain evolution will ultimately be necessary.

First, creating a comparative organoid model system using induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from various primates could be a solution scientists could employ. These organoids would be genetically manipulated using CRISPR-Cas9 to express or suppress human-specific genes such as NOTCH2NL, ARHGAP11B, and SRGAP2, which have already been used in organoids several times3‘6‘7‘17. By altering these genes and tracking changes in key traits such as neuronal proliferation, cortical folding, and synaptic connectivity, scientists could determine the functional roles of these genes across species. Comparative single-cell analyses already indicate prolonged neurogenic development and greater upper-layer neuron output in human organoids relative to non-human primates, aligning with species-biased progenitor dynamics17.

Second, researchers could incorporate environmental stressors into organoid cultures to simulate the same pressures humans faced throughout our evolution. It has been demonstrated that CBOs are suitable for studying developmental processes under controlled conditions13. Building on this, for instance, scientists could incorporate varying oxygen levels into organoids to mimic fluctuating climates over millennia, or they could add chemicals associated with social bonding and communication into organoids, which could possibly offer insights into how environmental and social factors influenced brain development. These experiments would help reveal how genetic adaptations have interacted with environmental conditions to drive neocortical complexity.

Finally, given the vast amounts of data generated through these experiments, leveraging advanced analysis techniques such as machine learning to identify patterns of interest present in the data could be a possible method. Machine-learning algorithms have been successfully applied to single-cell RNA-seq and live-imaging datasets to identify gene expression networks and cellular behaviors unique to human brain development32. These algorithms could help detect biological mechanisms that are beyond the grasp of human intuition, such as minor gene-expression patterns or minute cellular behaviors unique to human organoids. This approach of using machine learning would allow us to extrapolate potential ways humans evolved and predict how specific mutations or environmental factors might have shaped the human brain over time.

Conclusion

The integration of CBO technology and CRISPR genome editing marks a major leap in studying human neocortical evolution. These tools provide an unparalleled platform for exploring human-specific genes and their roles in shaping the neocortex. By bridging gaps in traditional models, the approach of using these technologies in tandem advances our understanding of the genetic and developmental mechanisms that define the neocortical uniqueness of humans. However, to fully uncover the divergence of human cognition, this review suggests using an approach that leverages various innovative technologies and methods to help unravel the complexity of human neocortical evolution.

Finally, to address ethical concerns surrounding the development of more complex organoid models, it will be vital to develop ethical guidelines and transparency frameworks. As a part of these guidelines, protocols for monitoring the potential emergence of consciousness-like activity in organoids, such as those suggested by Giandomenico and Lancaster29 will be essential, ensuring that experiments remain within ethical boundaries. These ethical guidelines will be crucial in helping to regulate the ever-increasing level of sophistication in organoids.

This review integrates recent advancements in CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing with organoid modeling, providing a novel framework for studying the genetic basis of neocortical evolution. By highlighting the limitations of current models and proposing a novel approach leveraging these technologies for future research, this review lays the foundation for continued research in integrating gene-environment interactions with human brain evolution.

References

- Nieuwenhuys, R., & Broere, C. A. J. A map of the human neocortex showing the estimated overall myelin content of the individual architectonic areas based on the studies of Adolf Hopf. Brain Structure and Function 222, 379–389. (2017). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Herculano-Houzel, S. The human brain in numbers: A linearly scaled-up primate brain. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 3(31), 1–11. (2009). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Florio, M., et al. Human-specific gene ARHGAP11B promotes basal progenitor amplification and neocortex expansion. Science, 347(6229), 1465–1470. (2015). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Molnár, Z., & Pollen, A. How unique is the human neocortex? Development, 141, 11–16. (2014). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Azevedo, F. A. C., et al. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 513(5), 532–541. (2009). [↩] [↩]

- Fiddes, I. T., et al. Human-specific NOTCH2NL genes affect Notch signaling and cortical neurogenesis. Cell, 173, 1356–1369.e22. (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Suzuki, I. K., et al. Human-specific NOTCH2NL genes expand cortical neurogenesis through Delta/Notch regulation. Cell, 173, 1370–1384.e16. (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Lancaster, M. A., et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature, 501, 373–379. (2013). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Giandomenico, S. L., et al. Cerebral organoids at the air–liquid interface generate diverse nerve tracts with functional output. Nature Neuroscience, 22(4), 669–679. (2019). [↩]

- Doudna, J. A., & Charpentier, E. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science, 346, 1258096. (2014). [↩] [↩]

- Heidenreich, M., & Zhang, F. Applications of CRISPR-Cas systems in neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17(1), 36–44. (2016). [↩]

- Memi, F., Ntokou, A., & Papangeli, I. CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing: Research technologies, clinical applications and ethical considerations. Seminars in Perinatology, 42(8), 487–500. (2018). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Boyd, J. L., et al. Human-chimpanzee differences in a FZD8 enhancer alter cell-cycle dynamics in the developing neocortex. Current Biology, 25(6), 772–779. (2015). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Somel, M., Liu, X., & Khaitovich, P. Human brain evolution: Transcripts, metabolites and their regulators. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(2), 112–127. (2013). [↩] [↩]

- Komor, A. C., Kim, Y. B., Packer, M. S., Zuris, J. A., & Liu, D. R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature, 533(7603), 420–424. (2016). [↩]

- DeFelipe, J. The evolution of the brain, the human nature of cortical circuits, and intellectual creativity. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 5(29), 1–15. (2011). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Pollen, A. A., et al. Establishing cerebral organoids as models of human-specific brain evolution. Cell, 176, 743–756.e17. (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Charrier, C., et al. Inhibition of SRGAP2 function by its human-specific paralogs induces neoteny during spine maturation. Cell, 149, 923–935. (2012). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Enard, W., et al. Molecular evolution of FOXP2, a gene involved in speech and language. Nature, 418(6900), 869–872. (2002). [↩]

- Ju, X. C., et al. The hominoid-specific gene TBC1D3 promotes generation of basal neural progenitors and induces cortical folding in mice. eLife, 5, e18197. (2016). [↩]

- Espinós, A., Fernández-Ortuño, E., Negri, E., & Borrell, V. Evolution of genetic mechanisms regulating cortical neurogenesis. Developmental Neurobiology, 82(7), 428–453. (2022). [↩] [↩]

- Lui, J. H., Hansen, D. V., & Kriegstein, A. R. Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell, 146(1), 18–36. (2011). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Pașca, A. M., et al. Human 3D cellular model of hypoxic brain injury of prematurity. Nature Medicine, 25(8), 1164–1174. (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Boldog, E., et al. Transcriptomic and morphophysiological evidence for a specialized human cortical GABAergic cell type. Nature Neuroscience, 21(9), 1185–1195. (2018). [↩] [↩]

- Sousa, A. M. M., Meyer, K. A., Santpere, G., Gulden, F. O., & Sestan, N. Evolution of the human nervous system function, structure, and development. Cell, 170(2), 226–247. (2017). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Hyun, I. The bioethics of stem cell research and therapy. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 120(1), 71–75. (2010). [↩]

- Kanton, S., et al. Organoid single-cell genomic atlas uncovers human-specific features of brain development. Nature, 574, 418–422. (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Camp, J. G., et al. Human cerebral organoids recapitulate gene expression programs of fetal neocortex development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(51), 15672–15677. (2015). [↩] [↩]

- Giandomenico, S. L., & Lancaster, M. A. Probing human brain evolution and development in organoids. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 44, 36–43. (2017). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Quadrato, G., Brown, J., & Arlotta, P. The promises and challenges of human brain organoids as models of neuropsychiatric disease. Nature Medicine, 22(11), 1220–1228. (2016). [↩]

- Qian, X., Song, H., & Ming, G. L. Brain organoids: Advances, applications and challenges. Development, 146(8), dev166074. (2019). [↩] [↩]

- Velasco, S., et al. Individual brain organoids reproducibly form cell diversity of the human cerebral cortex. Nature, 570, 523–527. (2019). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Rakic, P. Evolution of the neocortex: A perspective from developmental biology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(10), 724–735. (2009). [↩]

- Kelava, I., & Lancaster, M. A. Stem cell models of human brain development. Cell Stem Cell, 18(6), 736–748. (2016). [↩]

- Dell’Amico, C., Tata, A., Pellegrino, E., Onorati, M., & Conti, L. Genome editing in stem cells for genetic neurodisorders. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 182(3), 403–438. (2021). [↩]