Abstract

Filamentous fungi express complex behaviors, such as adaptive foraging, decision making, and memory-like phenomena. The complex behavior demonstrated by fungi suggests the existence of basal cognitive abilities in fungal mycelial networks; however, there is very little work providing insights into the underpinning mechanisms behind the basal cognition exhibited by fungi in the scientific literature. This comprehensive review aims to connect basal cognition in fungal networks to the electrophysiology of fungi. First, we outlined the electrophysiological underpinnings behind fungal excitability and reviewed how the frequency of the action potentials produced by some fungi can be increased with stimulation. We compared and reviewed electrophysiological data from multiple studies by pointing out what they have in common and identifying the sources of variability between them. Then, we reviewed how fungi exhibit a network intelligence through adapting their behavior according to their environment and proposed that this behavior is mediated by bioelectric signals communicated by the fungus.

Keywords: Basal cognition, Fungi, Action potentials, Network intelligence

Introduction

The scientific community has failed to agree upon an unambiguous definition for cognition; thus, a strong, biologically grounded definition is effectively nonexistent. However, an adapted quote taken from Lyon et al. provides the best insights into the issue: “A state of affairs is information for an organism if it triggers a change in physiology or behavior relative to that state of affairs. Whatever state of affairs induces a change in physiology or interactive potential in an organism is information for that organism”1. The properties of cognition, like acquiring information, integrating that information, using it to gain understanding, reacting to that information, and finally remembering that information, have helped organisms track and respond to their environments since the emergence of complex life. It will continue to support and enable complex life for millions, if not billions of years. Basal cognition refers to the ability of organisms lacking central nervous systems to cognize using a decentralized information processing system. Here, we examine fungi, more specifically mycelial networks, as biological systems capable of basal cognition.

Fungi are ubiquitously present in nearly every ecosystem on earth, and their presence is imperative to the survival of these ecosystems2. Of the estimated 5.1 million fungal species3, 40,000-50,000 of these fungi form mycorrhizal connections with plants and thus exist in the soil for long periods of time4. Fungi exist in aquatic ecosystems5, in urban environments6, in deserts7, in the snow of Antarctica8, from the Mariana Trench9, to Mount Everest10. Unlike other microbiota which also persist in these environments, such as bacteria and yeasts, filamentous fungi form sizable networks which exist in their environments for sustained periods of time.

The cells of filamentous fungi grow in threads, called hyphae, that range from 1-20 microns in diameter11. The hyphal tips extend via the internal hydrostatic pressure of the hypha, which pushes the cell wall outward and facilitates hyphal expansion12. As the hyphal tips extend, new hyphae branch from the original ones, which then branch again, rebranch, then fuse with one another. This creates a highly complex network that, with the right resources, can persist and expand indefinitely. The network generated from fungi, called a mycelium, grows underground and in the bodies of dead and dying organisms. They link the roots of 91% of all terrestrial plants13, which may use the mycelium as a medium of communication, and grow to become so dense that in a single gram of soil, there may exist many hundreds of meters of hyphae14. A single mycelium can weigh several tons and cover many hundreds of hectares15, creating an entangled net of mycelium that envelops the world. With fungi existing everywhere and growing to become some of the largest organisms on earth, fungi may represent one of the largest electrically communicating biological systems on our planet.

Action potential-like activity in Neurospora crassa was first reported by Slayman et al. (1976)16; the membrane potential of N. crassa repeatedly depolarized and then returned to its resting electronegative potential under a variable frequency. Then, fungi had not been examined as systems capable of basal cognition-like behaviors. It wasn’t until recent years that fungi were examined as biological networks capable of altering their physiology and growth according to their environments, speculatively exhibiting “decision-like” adaptive behaviors throughout their growth17. The finding that the electrical activity of soil-dwelling fungi is sensitive to stimulation18 was perhaps the first piece of evidence for the existence of an adaptive electrical signaling mechanism in mycelial networks. Instead of a network stochastically firing spontaneous action potentials that don’t adjust according to their environments or local stimuli, fungal networks can effectively adapt their electrophysiological activity to their environments, a phenomenon that could enable them to communicate their local state of affairs to distal parts of the network.

The capacity for a mycelial network to retain information regarding the locations of previously formed mycelial cords (thick, rope-like bundles of hyphae) or the locations of major resources would be advantageous in the case that a mycelial network becomes damaged and needs to be reformed. Fukasawa et al. (2019) observed this behavior in a cord-forming network by allowing the fungus to find the location of a resource, removing the network, and then observing polarized growth in the direction of the former resource. The authors interpreted this as a form of structural “memory” within the network, while also acknowledging that it could be a form of chemical or physical “memory” as well19.

In this review, we aim to outline the various characteristics of the action potential-like activity of fungi and compare them with neuron electrophysiology. We will review the electrogenic pump responsible for generating a resting membrane potential and the specific ion channels involved in initiating action potentials in fungi. The main issue that this paper addresses is the connection between basal cognitive behavior demonstrated by fungi, like the ability to solve problems, learn, and hold memories, with the endogenous electrical activity of fungi.

Methods

Relevant literature was identified using Google Scholar and PubMed under the key terms H+ATPase, Pma1, Fungal Hv1, Basal cognition, Fungal memory, Electrical activity, and Action potential. Studies showing relevance to the topic, such as studies presenting quantifiable electrophysiological data or fungal behavior potentially linked to bioelectric signaling. Only peer-reviewed studies published in English were selected for this study. Electrophysiological parameters, such as the resting membrane potentials of various fungi, voltage thresholds, I-V plots, pH dependencies of activation for Hv1 channels, and the frequency, magnitude, and timescale of action potentials, were extracted either from data tables or direct statements provided in the studies found. Broader concepts, like the adaptive foraging of fungi, the memory-like phenomena of fungi, and the mechanisms fungi use to manipulate hosts, were extracted as key concepts from relevant studies. Thematic analysis was used to identify a recurring pattern seen across studies, such as the commonality between various reported resting membrane potentials described for Neurospora crassa. Studies presenting results lacking in repeatability or interpretable data were, for the most part, excluded from the present study; however, some of these results were kept as “proof of concepts” to further solidify claims and to hopefully instigate further research.

Results

Spontaneous, Non-stimulable Action Potential-like Activity in Neurospora crassa

The electrical activity of fungi which most resembles that of neurons was first described by Slayman et al. (1976) in Neurospora crassa16. The electrical potential of the plasma membrane of N. crassa shifted towards a conspicuously positive potential, shifted back towards its electronegative resting state, hyperpolarized, and then, after a short-lived refractory period, returned to the resting membrane potential, close to perfectly resembling the action potentials generated by the neurons of animals. The authors found that N. crassa had a resting membrane potential of -180 mV, which shifts to approximately -40 mV during the peak of an “action potential.” The action potentials were long lasting, 1-2 minutes in length, accompanied by a 2- to 8-fold increase in membrane conductance during fast depolarization and a slight decrease in membrane conductance during slow depolarization.

The action potentials occurred spontaneously, without stimulation, at a considerably low frequency. The authors found that the frequency of action potentials could not be increased with stimulation and were not sensitive to injecting a current. Although the frequency of the action potentials produced by N. crassa was not sensitive to being stimulated, the action potentials produced by other soil-dwelling fungi were stimulable and will be further discussed in a later section.

Ion Gradients and Proton Dynamics in Fungal Action Potentials

The fungal Plasma Membrane H+-ATPase 1 (Pma1) is the main electrogenic pump responsible for moving protons out of the cell and was found to be responsible for polarizing the membrane potential of Neurospora crassa to the observed potential of -174 mV20. Inhibition of Pma1 results in the depolarization of the plasma membrane to the range of -40 mV to -70 mV.

The initiation of action potentials in fungi would not be possible without voltage-gated ion channels. The specific ion channels responsible for the generation of action potentials in N. crassa have been variably described between different studies, with one study reporting that chloride and potassium ion channels provide the greatest amount of voltage-dependent ion flux, with proton channels providing only a small amount of voltage-independent ion flux21, with another study reporting that voltage-gated proton channels provide the bulk amount of voltage-gated ion flux during the fungal action potential22. The discrepancies between these studies likely stem from variation in their experimental approaches, biological variability, or even subtle differences in variables such as pH or nutrient availability.

The finding that Pma1, which only moves H+, causes the plasma membrane to depolarize to the previously reported membrane potential of approximately -180 mV20‘16 suggests that hydrogen ions indeed provide the bulk of the ion influx involved in the generation of action potentials. The electrochemical gradient of H+, generated by Pma1, is what generates the high membrane potential20, meaning that protons experience a greater driving force than other ions, such as Na+, K+, Cl-, Ca2+, at the resting membrane potential. During the inhibition of Pma1, the membrane potential depolarizes to the same point that the membrane potential exists as during the peak of an action potential. It must be noted, however, that this is based on an approximation of electrophysiological data and that other ions may also play roles in establishing the resting membrane potential.

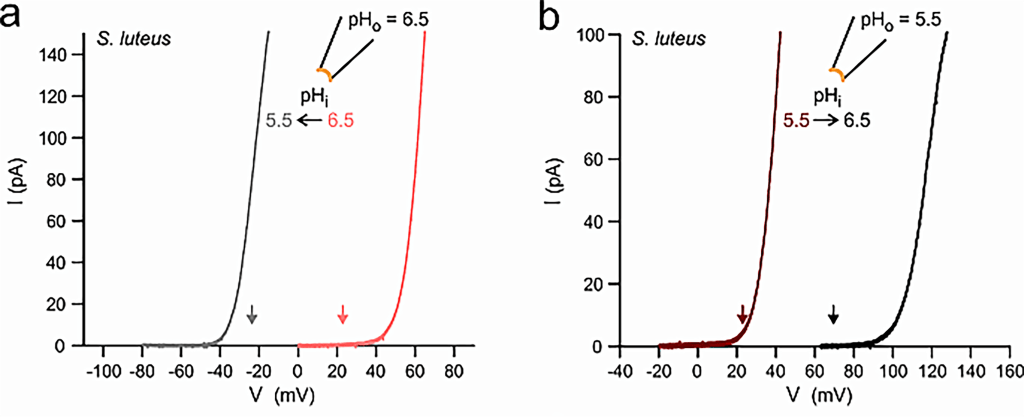

Fungal voltage-gated proton channels (Hvs) were first discovered and characterized by Zhao and Tombola, 202122. The authors found Hv1 homologs in species across all 5 five major fungal divisions, suggesting a broad conservation of Hv1 across the fungal kingdom. However, the authors focused on Hvs from two species: Suillus luteus (denoted as SIHv1) and Aspergillus oryzae (AoHv1), which shared a 25% sequence identity with one another.

eproduced from C. Zhao, F. Tombola. Voltage-gated proton channels from fungi highlight the role of peripheral regions in channel activation. Commun Biol. 4, 261 (2021). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Fungal Action Potentials are Sensitive to Stimulation: Armillaria bulbosa vs. Neurospora crassa

The action potential-like activity in mycelia is sensitive to various kinds of stimulation18. Olsson and Hansson found that the resting membrane potential of Armillaria bulbosa was between -70 to -100 mV, with action potentials having amplitudes of 5-50 mV, with a duration varying between 20 ms and 500 ms. Spontaneous action potentials, as described by Slayman et al. (1976) in N. crassa, occurred at frequencies between 0.5 to 5 Hz in A. bulbosa.

Olsson and Hansson found that the frequency of the action potentials decreased by injecting a negative current and increased by injecting a positive current through a microelectrode, suggesting that the ions involved in producing the action potentials have a positive charge. The authors also found that by adding a drop of sulfuric acid onto the mycelium 1-2 cm from the measurement electrode, the frequency of action potentials increased after approximately 30 s, suggesting that the signals propagated at a speed close to 0.5 mm/s. The most important finding, however, was that the frequency of action potentials also increased after placing a small wood block on the A. bulbosa mycelium 1-2 cm away from the electrode, but they did not increase after placing a block of perspex plastic of equal size and weight. The absence of a viable, modern replication of the Olsson and Hansson experiment is not due to a lack of interest but a lack of the use of advanced electrophysiological techniques capable of capturing fast and minuscule electrophysiological events. Authors such as Adamatzky et al. or Fukasawa et al. provided studies investigating stimuli-dependent bioelectric activity; however, their studies only showed extracellular recordings sampled at 1 hz, a frequency insufficient to resolve singular action potentials in fungal tissues. Using relatively large, subdermal microelectrodes in fungal tissues will only record a “spatial summation” of all the action potentials flowing through the hyphae at a given time, and not the action potentials flowing through individual hyphae. Changes in bioelectric activity as a result of other kinds of stimulation, like chemicals23, temperature24, or humidity24, have been described in the past; however, studies describing this behavior did not present results with parsable data or repeatability, leaving the original Olsson and Hansson experiment as the most reliable experimental evidence in this case.

The electrical activity described in N. crassa was not sensitive to stimulation in the way that the activity of A. bulbosa was16. The absence of stimulability in the action potentials of N. crassa means that the fungus cannot adapt its electrophysiological activity to its environment, but the presence of stimulability in other soil-dwelling species means that they can, in fact, adapt their electrical activity to their environments and implies not only a primitive form of sensory perception but a prerequisite for basal cognitive processes.

Mechanosensitive ion channels have been described in fungi in the past, but have primarily focused on Ca2+ and K+ channels25‘26. Further investigation of the possible presence and importance of mechanosensitive and chemosensitive H+ channels in fungi can further solidify the theory that fungi use bioelectric signals to communicate sensory information to other parts of the network, and that mechanical, chemical, and other kinds of stimulation can elicit bioelectric responses in fungal cells.

| Resting membrane potential | Duration | Amplitude | Resting frequency | Stimulability by current injection | |

| N. crassa | -170 – 200 mV | 1 – 2 min | ~ 140 mV | N/A | No |

| A. bulbosa | -70 – 100 mV | 20 – 500 ms | 5 – 50 mV | 0.5 – 5 Hz | Yes |

| Human | -70 mV | 1 – 2 ms | ~100 mV | 0.1 – 0.2 Hz; variable dependent on neuron class | Yes |

Action Potential-mediated “Memory” Behavior in Fungi

The ability of cord-forming fungi to “remember” the locations of resources and the locations of their own mycelial cords is likely advantageous in the case that the network becomes damaged and needs to be restored. It has been shown that upon “discovering” (foraging mycelia coming into contact with a resource) a new resource (such as a block of wood), cord-forming fungi redistribute their biomass in the direction of the food resource29, which is accompanied by a thickening of the cord connecting the original mycelial source and the new resource. When the network becomes damaged and all of the cords, along with the bait, are removed, the fungus “remembers” the location of the resource, demonstrated by sending more biomass in the direction in which the resource used to be19, even without the new fungal growth being in contact with the wood.

It is a possibility that the fungus’ apparent “awareness” of the resource, (demonstrated by a polarized growth towards a food resource upon foraging mycelia coming into contact with the resource), is initiated, or “signaled,” by an increase in the frequency of action potentials flowing from the foraging mycelia towards the center of the network, a phenomenon demonstrated by Olsson and Hansson, 199518. And, thus, the memory of polarized growth towards the resource after the network’s removal is initiated in the same way, and then is possibly stored in the bioelectric network that remains untouched in the source block of mycelium30.

These hypotheses are admittedly speculative, as the memory-like behavior showcased in fungi from the study mentioned above could have emerged from possible biochemical residues left on the growth medium, or the simple fact that more fungal biomass was located in the direction of food recourse, as mentioned by the authors of this study. The observed memory behavior in fungi suggests a role in bioelectric signaling, but the direct connection between fungal memory and action potentials remains highly speculative. Future experiments could consolidate this link, such as utilizing multi-electrode arrays to map action potential propagation during memory-forming tasks, or seeing if H+ flux inhibition could suppress fungi’s ability to form memories. Further study could distinguish between chemical and electric memory in fungal networks by identifying chemical residues left over by the mycelial network and testing to see if those chemicals could be used to influence or direct the growth of new mycelial cords.

The same electrophysiological mechanisms that enable basal cognition in single mycelial networks may also allow information sharing throughout multiple fungal colonies as long as they are connected through hyphae. A study done in 202431 showed that “Spatial resource arrangement influences network structures of mycelia” and demonstrated that multiple mycelial colonies can encounter each other, fuse, and then share information and resources. The growth polarity of mycelial colonies can be described as acropetal, meaning that they grow from the center outwards. The mycelia initially grew radially, starting at the blocks and growing outwards, until coming into contact with the mycelium from the other blocks, where they then fused to generate one large mycelium. After fusion, the topology of the colonies changed drastically, forming thickened chords between each of the starting blocks and creating a dense network of chords that resembled the shape targeted in the experiment. Oscillations in electrical activity and nutrient transfer normally existing in mycelia32‘33 began to coincide with one another following fusion, suggesting that “Fungal mycelia may be capable of processing information about spatial locations within their networks and adaptively altering their behavior” as a singular large mycelium rather than multiple individuals.

While this review has focused on internal electrical communication in fungi, some fungal species may engage in electrophysiological interactions with other organisms. Ophiocordyceps unilateralis sensu lato, for example, is well known to cause the ‘zombie ant’ phenomenon by manipulating the behavior of its host insects34. The mechanisms of host manipulation are widely considered to be facilitated by chemical secretions by the fungus; however, the fungus also invades host tissue and inserts hyphal projections directly into the host muscle fibers35, raising the question of whether or not fungal action potentials could play a role in infected muscle contraction. Testing whether the electrical activity of Ophiocordyceps and the movement of infected muscles coordinate with each other and seeing whether inhibiting Ophiocordyceps Hvs also silences the fungus’s control over the insect are good ways to test the possible role of bioelectricity in host manipulation.

The hypothetical existence of electrically communicated signals being conveyed by individual Ophiocordyceps colonies, linked through hyphae, during an active infection may yield the collective network of mycelia throughout the insect’s body with the ability to “learn” its host’s anatomy. Whether the host specificity of Ophiocordyceps is attributable to its cuticle sensitivity, enzyme specificity, or anatomical specificity is unknown, but if control over the host’s anatomy is indeed a learned behavior by the fungus, and not the consequence of a kind of “somatic memory,” then information extension between fungal colonies during the infection is crucial and suppressing it would be detrimental to the fungus’ control.

Discussion

Pma1 is a transmembrane enzyme that utilizes active transport to move H+ out of the fungal cell and generate a concentration gradient for H+. The voltage generated by the concentration gradient of H+, or the resting membrane potential, is species-specific. In N. crassa, it was approximately -180 mV and in A. bulbosa, it was between -70 and -100 mV. A fungal voltage-gated proton channel, Hv1, was found to exist in broad conservation throughout the fungal kingdom in sequences from each major division of fungi, and the I-V plots, reversal potentials, and pH dependencies of activation were all different for each species’ Hv1. It must be noted, however, that studies show that other ions, such as potassium or chloride ions, provide the primary currents involved in action potentials, and this must be studied further to ascertain which ions provide the greatest flux.

Under normal conditions, where the fungi were not being stimulated, the action potentials occurred at a low, consistent frequency. The frequency of the action potentials could be increased by injecting a positive current, which aligns with the finding that cations (possibly H+) are the ions involved in the generation of action potentials. The frequency could also be increased by damaging the hyphae with HCl or by stimulating them with a food resource, like placing a wood block on the mycelium. The frequency did not increase after placing a plastic block of equal size and weight, which suggests that the fungus was not stimulated by physical pressure but rather the wood itself.

The flow of action potentials being sent by the hyphal tips (that eventually reach the center of the network) may represent a mechanism of communicating the location of a resource; the network responds to the electrical stimulus by reallocating biomass to increase the degree of connection between the network and the resource, thus, increasing the efficiency of nutrient transfer. When the hyphae of multiple colonies fuse, they synchronize their individual oscillations in electrical activity and gain the ability to share the locations of known resources. Then, they can work together to process spatial information, recognize shapes, and coordinate growth and nutrient transfer across the collective network. After the fungal biomass is removed, leaving only the source block of mycelium, the colony regenerates with a polarized growth in the direction of the former resource, exhibiting a memory behavior that may be retained in the bioelectric state of residual mycelium. Action potentials may serve as the physiological basis for a primitive version of sensory perception, information integration, and reacting to that information through differentiated growth patterns.

Future research on this topic should pertain to studying the pattern and frequency of action potentials involved in signaling various kinds of stimulation in the fungus. The Olsson and Hansson experiment should be repeated by stimulating the tips of foraging hyphae and placing a multi-electrode array down the mycelial cords preceding the hyphal tips to measure the flow and direction of action potentials and determine where the fungus directs the action potentials towards. Mapping the propagation of action potentials through mycelial networks as they process various kinds of sensory information or perform memory-forming tasks would provide insights into how exactly they process this information and may further link the bioelectricity of fungi with basal cognition.

Looking for and describing variations of Pma1 and Hv1 across the fungal kingdom in as many different species as possible is advantageous for further documenting the electrophysiology of fungi. A model species of fungi displaying action potentials with a sensitivity to stimuli (as seen in A. bulbosa) with known Pma1 and Hv1 kinematics would provide deeper insight into the electrophysiology of fungi, how it compares with the electrophysiology of the neurons of animals, and the greater implications of fungal electrophysiology, such as cognition and extending their bioelectric authority onto other organisms. Seeing how inhibiting Pma1 and Hv1 in fungi affects their ability to generate action potentials would further confirm the roles of Pma1 and Hv1 in action potential generation and studying how Pma1 and Hv1 inhibition affects Ophiocordyceps’ and other species’ ability to manipulate their hosts would provide insight into the role of bioelectricity in host manipulation. Further study of the “memory-like” behavior expressed in cord-forming networks could distinguish between chemical and electric memory by identifying chemical residues left over by the mycelial network and testing to see if those chemicals could be used to influence the growth of mycelial cords.

Testing the role of bioelectric activity in Ophiocordyceps’ manipulative authority over its hosts would link bioelectricity in fungi with a complex, observable behavior elicited by the Ophiocordyceps-controlled insect. If host manipulation is indeed bioelectric in nature, then removing the gene encoding Ophiocordyceps’ Hv1 channel or inhibiting the Hv1 channel should suppress the ability of the fungus to control its host insects.

In closing, the electrophysiology of fungal hyphae exhibits striking similarities to that of animal neurons, like the mechanisms of signal transduction, having a resting membrane potential generated by positive ions, spontaneously producing a stream of action potentials to be prepared for stimuli, and the ability to be stimulated to increase their frequency of action potentials. Fungi can utilize their bioelectric networks to give themselves basal cognitive capabilities, like taking in sensory information, integrating that information, reacting to that information, and storing that non-genetic information in their networks as “memories.” Fungal networks are ubiquitously present on our planet, often existing as interconnected collective networks, potentially making them some of the largest electrically communicating biological systems on earth.

References

- P. Lyon, F. Keijzer, D. Arendt, M. Levin. Reframing cognition: getting down to biological basics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 376, (2021). [↩]

- M. Buckley. The fungal kingdom: diverse and essential roles in earth’s ecosystem. American Society of Microbiology. (2007). [↩]

- M. Blackwell. The fungi: 1, 2, 3 … 5.1 million species? American Journal of Botany. 93, 426-438 (2011). [↩]

- M. G. A. van der Heijden, F. M. Martin, M. A. Selosse, I. R. Sanders. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: the past, the present, and the future. New Phytol. 205, 1406-1423 (2015). [↩]

- H. P. Grossart, S. V. den Wyngaert, M. Kagami, C. Wurzbacher, M. Cunliffe, K. Rojas-Jimenez. Fungi in aquatic ecosystems. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 17, 339-354 (2019). [↩]

- M. Newbound, M. A. Mccarthy, T. Lebel. Fungi in the urban environment: a review. Landscape and Urban Planning. 96, 138-145 (2010). [↩]

- M. Murgia, M. Fiamma, A. Barac, M. Deligios, V. Mazzarello, B. Paglietti, P. Cappuccinelli, A. Al-Qahtani, A. Squartini, S. Rubino, M. N. Al-Ahdal. Biodiversity of fungi in hot desert sands. Microbiology Open. 8, (2019). [↩]

- G. C. de Menezes, S. S. Amorim, V. N. Goncalves, V. M. Godinho, J. C. Simoes, C. A. Rosa, L. H. Rosa. Diversity, distribution, and ecology of fungi in the seasonal snow of antarctica. Microorganisms. 7, 445 (2019). [↩]

- Z. Wang, Z. Liu, Y. Wang, W. Bi, L. Liu, H. Wang, Y. Zheng, L. Zhang, S. Hu, S. Xu, P. Zheng. Fungal community analysis in seawater of the Mariana Trench as estimated by Illumina HiSeq. RSC Advances, 9 6956-6964 (2019). [↩]

- M. C.W. Lim, A. Seimon, B. Nightingale, C. C.Y. Xu, S. R.P. Halloy, A. J. Solon, N. B. Dragone, S. K. Schmidt, A. Tait, S. Elvin, A. C. Elmore, T. A. Seimon. Estimating biodiversity across the tree of life on Mount Everest’s southern flank with environmental DNA. iScience. 25, (2022). [↩]

- R. A. Zabel, J. F. Morrel. Hypha- an overview. Wood Microbiology (Second Edition). 3, 55-98 (2020). [↩]

- N. P. Money. Insights on the mechanics of hyphal growth. Fungal Biology Reviews. 22, 71-76 (2008). [↩]

- H. Hawkins, R. I.M. Cargill, M. E. Van Nuland, S. C. Hagen, K. J. Field, M. Sheldrake, N. A. Soudzilovskaia, E. T. Kiers. Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Current Biology. 33, R560-R573 (2023). [↩]

- J. M. Lynch, E. Bragg. Microorganisms and soil aggregate stability. Advances in soil science. 2. 133-171 (1985). [↩]

- M. L. Smith, J. N. Bruhn, J. B. Anderson. The fungus Armillaria bulbosa is among the largest and oldest living organisms. Nature, 356, 428 (1992). [↩]

- C. L. Slayman, W. S. Long, D. Gradmann. “Action potentials” in Neurospora crassa, a mycelial fungus. Science. 192, pg. 264–267 (1976). [↩] [↩] [↩] [↩]

- N. P. Money. Hyphal and mycelial consciousness: the concept of the fungal mind. Fungal Biol. 123, 845-850 (2019). [↩]

- S. Olsson, B. S. Hansson. Action potential-like activity found in fungal mycelia is sensitive to stimulation. Naturwissenschaften 82, 30–31 (1995). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Y. Fukasawa, M. Savoury, & L. Boddy. Ecological memory and relocation decisions in fungal mycelial networks: responses to quantity and location of new resources. ISME J 14, 380–388 (2020). [↩] [↩]

- D. Gradmann, U. P. Hansen, W. S. Long. Current-voltage relationships for the plasma membrane and its principal electrogenic pump in Neurospora crassa: I. Steady-state conditions. J Membr Biol. 39, 333–367 (1978). [↩] [↩] [↩]

- R. R. Lew. Ionic currents and ion fluxes in Neurospora crassa hyphae. Journal of experimental botany. 58, 3475-3481 (2007). [↩]

- C. Zhao, F. Tombola. Voltage-gated proton channels from fungi highlight the role of peripheral regions in channel activation. Commun Biol. 4, 261 (2021). [↩] [↩]

- A. Adamatzky, A. Gandia, A. Chiolerio. Fungal sensing skin. Fungal Biol Biotechnol. 8, 3 (2021). [↩]

- Y. Fukasawa, D. Akai, M. Ushio, T. Takehi. Electrical potentials in the ectomycorrhizal fungus Laccaria bicolor after a rainfall event. Fungal Ecol. 63, 101229 (2023). [↩] [↩]

- M. Zhou, Y. Wang, Y. Qi, X. Li, Y. Zhang. The Neurospora crassa homolog of bacterial mechanosensitive channels is required for hyphal morphogenesis and osmotic stress response. Fungal Genet Biol. 112, 43–51 (2018). [↩]

- B. M. Bönemann, A. Mayer, P. Kugler. The yeast vacuolar membrane TRP channel, TRPY1, is a mechanosensitive osmosensor. FEBS Lett. 586, 2995–2999 (2012). [↩]

- D. Purves, G. J. Augustine, D. Fitzpatrick, W. C. Hall, A.-S. LaMantia, R. D. Mooney, M. L. Platt, L. E. White. Neuroscience. 6th ed. Sinauer Associates (2018). [↩]

- R. Brette. Integrate-and-fire models. In: Encyclopedia of Computational Neuroscience. Springer, 1–9 (2015). [↩]

- L. Boddy, J Hynes, D. P. Bebber, M. D. Fricker. Saprotrophic cord systems: dispersal mechanisms in space and time. Mycoscience 50, 9-19 (2009). [↩]

- M. levin. Endogenous bioelectrical networks store non-genetic patterning information during development and regeneration. J Physiol. 592(11), 2295-2305 (2014). [↩]

- Y. Fukasawa, K. Hamano, K. Kaga, D. Akai, T. Takehi. Spatial resource arrangement influences both network structures and activity of fungal mycelia: a form of pattern recognition? Fungal Ecol. 72, 101387 (2024). [↩]

- M. D. Fricker, M. Tlalka, D. Bebber, S. Tagaki, S. C. Watkinson, P. R. Darrah. Fourier-based spatial mapping of oscillatory phenomena in fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 44, 1077–1084 (2007). [↩]

- Y. Fukasawa, D. Akai, T. Takehi, Y. Osada. Electrical integrity and week-long oscillation in fungal mycelia. Sci Rep. 14, 15601 (2024). [↩]

- H. C. Evans, S. L. Elliot, D. P. Hughes. Ophiocordyceps unilateralis: a keystone species for unraveling ecosystem functioning and biodiversity of fungi in tropical forests? Commun Integr Biol. 4, 598–602 (2011). [↩]

- C. A. Mangold, M. J. Ishler, R. G. Loreto, M. L. Hazen, D. P. Hughes. Zombie ant death grip due to hypercontracted mandibular muscles. J Exp Biol. 222, jeb200683 (2019). [↩]