Abstract

Visual Studio Code (VS Code) extensions enhance productivity but pose serious security risks by inheriting full IDE privileges, including access to the file system, network, and system processes. We present the first automated solution that profiles, sandboxes, and enforces least-privilege execution policies for VS Code extensions at runtime. The system begins with a multi-layered static risk assessment that combines metadata inspection, supply chain auditing, AST-based code analysis, and LLM inference to identify sensitive behaviors and assign a risk category: reject, unrestricted, or sandbox. For sandboxed extensions, it generates fine-grained policies by mapping required Node.js APIs and dynamically constructed resources such as paths, endpoints, and shell commands. A combination of static analysis and dynamic runtime behavior offer a complete view of extension’s behavior. Enforcement is handled via a custom in-process sandbox that isolates extension behavior using dynamic require patching and proxy-based wrappers, without modifying VS Code’s core or affecting other extensions running within the same Extension Host. In a study of 377 extensions, 26.5% were high-risk, reinforcing the need for sandboxing. To evaluate the methodology described in the paper, the top 25 trending extensions were evaluated through static and dynamic analysis: 64% ran successfully while enforcing the sandbox policies generated through static analysis only, while 100% of them worked while enforcing the policy generated through a combination of static and dynamic analysis. Static analysis captured 95.9% of permissions required for an extension to function; dynamic monitoring covered the rest, ensuring that extensions do not break during use.

Keywords: VS Code extension, sandboxing, AST, static analysis, threat modeling, LLM, software supply chain, dynamic behavior modeling

Introduction

Visual Studio Code (VS Code) is a lightweight, open-source code editor developed by Microsoft that has become one of the most popular development environments worldwide due to its speed and customizability. Its power is significantly amplified by a vast ecosystem of extensions. However, this extensibility introduces a critical security challenge: VS Code extensions typically inherit the full privileges of the IDE. This unrestricted access allows extensions to interact with the file system, network, and system processes, meaning a single compromised extension can jeopardize the entire development environment. Several studies have confirmed that malicious VS Code extensions can exfiltrate credentials, modify files, and act as spyware by abusing trusted APIs1‘2 VS Code’s security team has also been removing malicious extensions they have found on the marketplace; however, by the time the extensions are removed, they have already had the opportunity to do harm3.

The core problem, identified by multiple security analyses, is VS Code’s lack of granular security controls for extensions. This paper addresses an important question: how can developers safely leverage VS Code extensions without unacceptable security exposure? Our solution enables secure execution by first rigorously assessing an extension’s risk profile. Malicious extensions are identified for rejection. For those deemed highly vulnerable but not malicious, our solution focuses on auto-generating precise sandboxing policies which can then be enforced during runtime, protecting the developer from vulnerable actions. This is achieved by identifying data sinks–extensions’ interactions with the file system, network, and data.

The Security Challenge and Need for Automated Extension Risk Management

VS Code extensions are implemented as Node.js applications, primarily written in JavaScript or TypeScript. As such, they inherit the full capabilities of the Node.js runtime; including access to the filesystem, network, and OS-level processes; without sandboxing or permission enforcement. This execution model exposes the IDE to severe security risks. A compromised extension can act with full local privileges compromising the entire local system. A systematic analysis revealed that 8.5% of 27,261 analyzed real-world VS Code extensions expose sensitive developer data, such as access tokens and configuration files4.

Extensions operate with unrestricted access to VS Code’s runtime environment. This allows a single malicious extension to exfiltrate data, modify user files, or establish persistence. Supply chain attacks through nested npm dependencies often go undetected, and developers lack tools to inspect or reason about extension behavior. Existing endpoint or antivirus tools are insufficient5‘6, as they do not account for the unique structure and privilege model of IDE-based plugins or too much trust is given to VS Code’s system.

Manual security auditing of the tens of thousands of VS Code extensions is impractical. The rapid pace of extension updates and the complexity of modern JavaScript/TypeScript codebases make human-only analysis insufficient.

An automated system addresses these challenges by enabling scalable and real-time analysis. Such a system can apply uniform criteria across the ecosystem, quickly triage new submissions, and detect security vulnerabilities introduced in updates. Beyond simple detection, automation enables the enforcement of fine-grained, least-privilege sandboxing policies. These policies can be informed by both static and dynamic analysis, offering a nuanced alternative to the current all-or-nothing trust model.

This approach transforms the security model from all-or-nothing to nuanced risk management. Researchers have expressed concern over the fact that extensions execute with the same privileges as the host IDE, without sandboxing or visibility7. Automated risk profiling enables a shift from binary trust models to nuanced, policy-driven enforcement. Developers can safely adopt powerful extensions under enforceable constraints. Extension authors receive actionable feedback, improving ecosystem hygiene. This architecture provides a scalable path to securing VS Code without sacrificing extensibility or productivity.

The Three-Step Solution

Our proposed solution for securing VS Code extensions is structured as a three-stage pipeline. Each stage builds upon the preceding one, enabling the system to move from coarse-grained risk identification to precise behavior confinement.

Methodology

High Level Overview of the Three Step Solution

Step 1: Extension Evaluation and Risk Profiling

The first stage of the pipeline conducts a multi-layered risk assessment that incorporates metadata, supply chain dependencies, and static code analysis. The initial screening examines the extension’s publisher profile and declared metadata, using indicators such as publisher reputation, install base, and frequency of updates. In documented cases, attackers have published look alike extensions that mimicked trusted tools to carry out credential theft8. Reviewing the publisher profile helps detect such impersonation attacks.

Next, the solution evaluates the extension’s dependency tree to identify vulnerable or suspicious packages. This includes scanning for known CVEs, unmaintained modules, and indicators of malicious installation behavior, such as post-install scripts or unexpected network requests.

Finally, a deep static analysis phase is performed on the extension’s JavaScript or TypeScript code using an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) based engine augmented by Large Language Models (LLMs). This analysis maps sensitive operations such as filesystem interactions, process invocations, and network communications into a behavioral profile. Based on this composite view, the system categorizes the extension into one of three buckets: rejected (if malicious), unrestricted (if clearly benign), or sandboxing candidate (if highly vulnerable).

Step 2: Automated Sandbox Policy Generation

For extensions deemed suitable for sandboxing, the solution proceeds to automatically generate fine-grained, least-privilege sandboxing policies. This begins with the construction of a complete dependency graph, mapping all direct and transitive imports used throughout the extension’s codebase. This graph allows the system to determine exactly which Node.js core modules and APIs are required for execution.

Function-level analysis is then conducted using AST traversal techniques. The engine identifies the precise functions invoked within sensitive modules, such as fs.readFile, child_process.exec, or http.request. This produces a whitelist of API calls that constitute the extension’s behavior.

LLMs9‘10 have been shown to demonstrate impressive reasoning abilities in natural and programming languages tasks via fewshot11 and chain-of-thought12 prompting. Utilizing this ability, in order to resolve dynamic runtime targets such as file paths assembled from user input or URLs constructed through template strings, the system invokes an LLM through a refined prompt. The model analyzes the first-party code (excluding third-party dependencies) and produces a structured output describing all accessed resources, which includes justification for each resolution.

The system then transitions to dynamic monitoring. In this mode, the extension is observed in a non-enforcing sandbox for a limited period (e.g. 7 day period). All files accessed, commands executed, and network endpoints contacted are logged, forming an empirical baseline. This hybrid model of using static analysis and observing dynamic behavior ensures coverage across all extension functionality. This is similar to Chestnut13, which generates per-app seccomp policies for native OS applications via a compiler pass, then optionally refining them with dynamic tracing.

Step 3: Runtime Policy Enforcement

The final stage of this solution involves runtime enforcement of the generated policies. This is accomplished via a custom sandboxing architecture implemented directly within the VS Code Extension Host process. While Microsoft has implemented VS Code process sandboxing14, this paper extends the principles to extensions, ensuring compatibility across platforms and not requiring changes to the VS Code core.

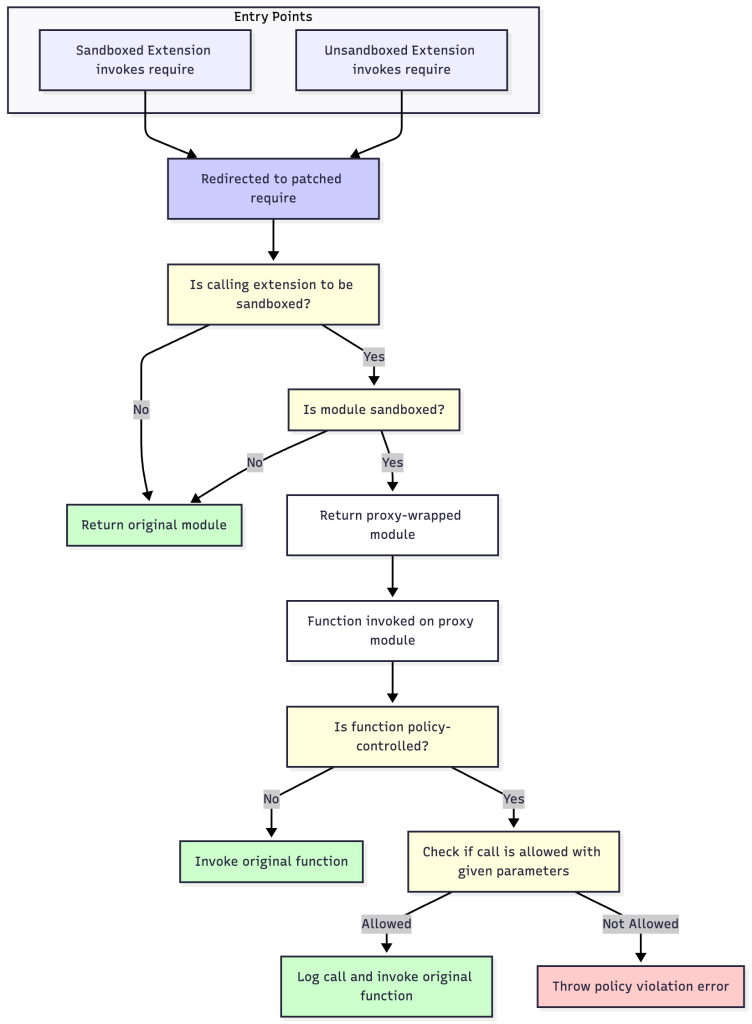

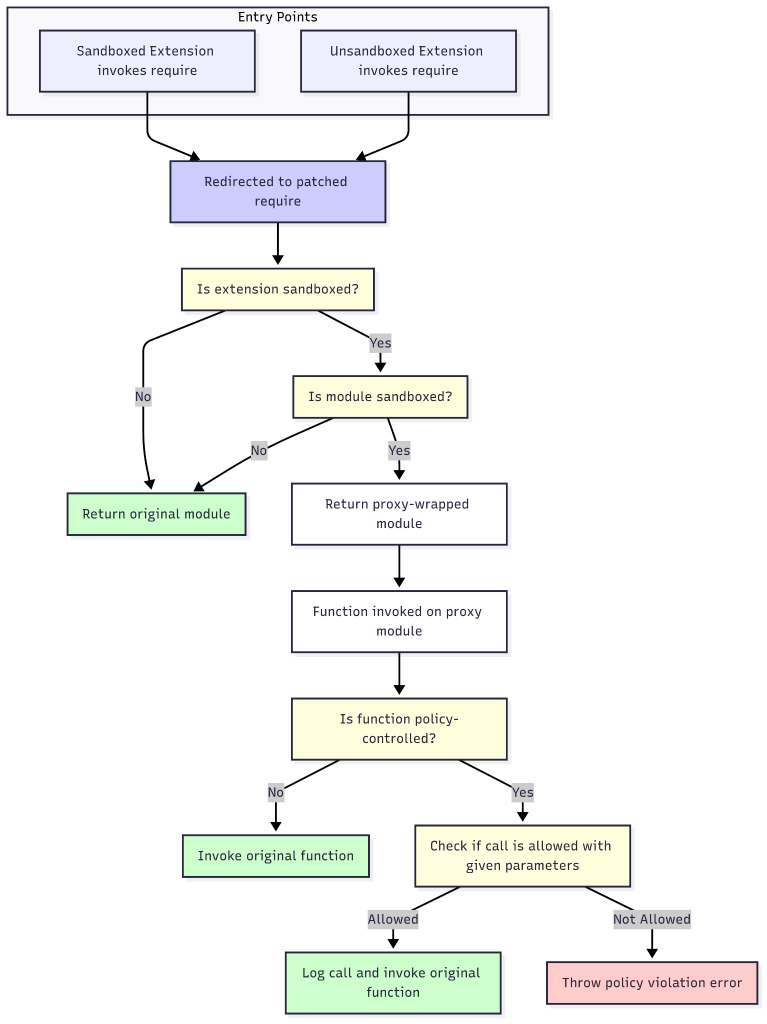

The enforcement layer operates by intercepting Node.js’s module loading system using dynamic require patching. When an extension attempts to load a module, the system verifies whether it is operating within a sandboxed context. If so, it provides a proxy-wrapped version of the module that enforces resource access policies at the function level.

From this point onwards, the extension runs under an explicit allow-list (“default-deny”) runtime policy. All operations that are explicitly permitted by the policy execute; any operation not explicitly listed is blocked and an error is logged.

The enforcement is restricted to the specific extension under evaluation. This prevents interference with other extensions. This enforcement structure ensures seamless integration that doesn’t affect other extension’s functionality.

In-Depth Extension Evaluation and Risk Profiling

Our extension evaluation system employs a multi-layered, automated approach, with each layer providing increasingly detailed risk assessment data. This is accomplished through a suite of analysis services that examine the extension’s metadata, supply chain, and code, resulting in a granular risk score.

Layer 1: Metadata and Publisher Analysis

This initial screening provides a rapid risk assessment based on observable characteristics, viz the metadata and permissions required by the extension.

Publisher and Marketplace analysis: This analysis uses data from extension-info.json file, which contains marketplace data. It assesses publisher reputation by checking for domain verification and analyzes community engagement through metrics like install counts and average ratings. A low install count (<500) combined with a low rating count (<10) is flagged as a low-popularity risk factor, suggesting limited community scrutiny. The analysis also checks for outdated extensions, flagging any that have not been updated in over two years as a medium risk. As AquaSec has shown8, masquerading popular extensions is a known attack vector, and this analysis intends to shed light on such extensions.

Declared Intent and Permissions analysis:

The Permission analysis statically analyzes the package.json manifest to evaluate an extension’s requested permissions and capabilities. This information is explicitly defined in the extension manifest15:

Activation Events: This analysis identifies the use of broad activation events like * or onStartupFinished, which causes an extension to load early or be persistently active. This is flagged as a medium risk because it unnecessarily increases the extension’s exposure.

Sensitive Contributions: The manifest’s contributes section is scanned for high-risk contribution points. For instance, contributing debuggers, terminal profiles, or taskDefinitions are considered medium risk as these capabilities can execute arbitrary code. Contributing authentication providers are also flagged as medium risk because it involves handling credentials.

Layer 2: Supply Chain Security Assessment

The solution also performs a deep dive into the software supply chain.

Known Vulnerability Detection:

Dependency Auditing: The Dependency analysis executes npm audit16 on the extension’s package.json. If a package-lock.json file is present, it is used for the most accurate audit. If not, the service creates a temporary directory, runs npm install, and then performs the audit. Vulnerabilities are mapped from npm’s severity levels (moderate, high, critical) to our internal risk scores. As Node.js packages operate with high privileges ensuring that specific versions of the packages being used don’t have vulnerabilities is essential17.

OSSF Scorecard analysis: The OSSF Score18 analysis provides a security health check for the project’s repository and its direct dependencies. It automatically discovers the repository URL by first parsing the VSIX extension.vsixmanifest file for source code links and falls back to the repository field in package.json. The OpenSSF Scorecard tool assesses the repository on various security checks, including code review practices, vulnerability disclosure policies, and testing. A score below 3 is considered high risk, while a score between 3 and 6 is medium risk. This score is a key indicator of the project’s overall security maturity. However, it is important to note that the OSSF Scorecard analysis is more effective for Github workflows and thus non-Github workflows may receive a lower score19.

Malicious Behavior and Sensitive Data Detection:

Malware Scanning: We use VirusTotal20 service, an enterprise grade service from Google, to scan the extension package (.vsix) by first calculating its SHA256 hash and checking for existing reports. If no report is found, the file is uploaded for analysis. The risk is assessed based on the detection ratio from about 70 antivirus engines, which keeps the false negatives low. Moreover, we apply a threshold (e.g., requiring more than one engine to flag the extension as malicioius) before treating an extension as malicious, which helps keep false positives low.

Sensitive Information Leakage: The Sensitive Info analysis uses the ggshield21 command-line tool to perform a recursive scan of the extension’s source code. It executes ggshield secret scan path –recursive –json and processes the JSON output to identify hardcoded secrets like API keys, private credentials, and tokens. Each finding is categorized, and its value is redacted for safe reporting. These publicly-available secrets are vulnerabilities which potential attackers can use to get access to sensitive information or key operations.

Code Obfuscation: The Obfuscation detection analyzes the code for signs of intentional obfuscation, to expose malicious extensions that use obfuscated code to bypass review processes. It calculates the Shannon entropy22 of files to detect packed or encrypted data, identifies the use of hexadecimal or Unicode encoding, and flags the presence of long, minified lines of code. For smaller files, it performs a full AST analysis to detect techniques like control-flow flattening.

Network Communication Anomalies: The Network Endpoint analysis parses the AST to extract all domain names and IP addresses. It validates domains via DNS checks and then uses the VirusTotal API to check the reputation of all public endpoints. This is to make sure that the extensions aren’t sending or obtaining data from any dangerous network endpoints.

Layer 3: Deep Code Analysis and Behavioral Profiling

The AST analysis is the core of this layer, performing static analysis of the code’s behavior, similar to ODGen23, however optimized for speed by incorporating some of the concepts from GraphJS24 and FAST25. It parses all JavaScript/TypeScript files into Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs) using @babel/traverse library which utilizes a depth-first traversal algorithm. In order to ensure that AST isn’t built repeatedly, care is taken that when each node is visited during the traversal, multiple rules based scans are done where each scan is highly specialized and looking for a single-purpose vulnerability/threat. It then uses LLMs to adjudicate the findings to reduce the number of false positives, inspired in large part by research into using LLMs to adjudicate static-analysis alerts26.

Code Execution and Injection:

Command Injection: This phase tracks the usage of the child_process module. It flags any use of exec or spawn where the command argument is constructed dynamically (e.g., through string concatenation or template literals), as this is a classic command injection method. The rules also check if the shell: true option is used, which is a high-risk practice. Unsafe Code Patterns: This rule set detects the use of eval(), new Function(), and setTimeout with string arguments, all of which can fetch and execute code during runtime bypassing any static security analysis.

Filesystem and Data Security:

Sensitive Path Access: This rule set checks for filesystem operations that interact with sensitive file locations. It uses a predefined list of high-risk path patterns, which includes browser profiles, SSH keys (~/.ssh), and cloud credentials (~/.aws/credentials). Extensions accessing sensitive paths are more risky for developers to utilize. Cryptographic Weaknesses: This rule set identifies the use of weak hashing algorithms (MD5, SHA1), insecure ciphers (DES, RC4), the use of static or hardcoded initialization vectors (IVs), and insufficient iteration counts in PBKDF2. Prototype Pollution: This rule set detects common prototype pollution patterns27, such as direct assignment to __proto__ or unsafe object merging with functions like Object.assign.

Risk Scoring and Aggregation

Our solution employs a quantitative risk scoring system to provide a consistent and objective assessment, similar to UntrustIDE, which labeled over 700 extensions by exploitability and behavior1. Each finding from the analysis services is assigned a risk level–low, medium, high, or critical. These levels are mapped to numerical values for aggregation: low = 0, medium = 1, high = 2, and critical = 3.

The overallRisk for a given analysis module (e.g., dependencies, metadata) is determined by the highest risk score found within that module. For example, the Dependency analysis assigns an initial risk of low to each dependency and then updates it based on the highest severity vulnerability found by npm audit. Similarly, the Permission analysis aggregates risk factors from the manifest; a single high risk factor will elevate the module’s overall risk to high.

Finally, these risk scores are aggregated to produce a comprehensive risk profile for the extension. This informs the decision to accept, reject, or sandbox it. This granular, bottom-up approach to scoring ensures that even a single critical issue in one area is not overlooked.

| Analysis Module | Sub-Component / Check | Risk Score / Severity Logic | Notes |

| Publisher and Marketplace | Low Install Count & Ratings | installCount < 500 AND ratingCount < 10 -> Medium | |

| Unverified Publisher | isVerified: false -> Medium | ||

| Outdated ( > 2 years) | lastUpdated is over 2 years ago -> Medium | ||

| Intent and Permissions | Activation Events | Presence of one or more following: Broad Activation (*) onStartupFinished -> Medium | |

| Sensitive Contributions | Presence of one or more following: Task definitions Terminal profiles Debugger Contribution -> Medium | ||

| Dependency auditing | npm audit Vulnerabilities | Direct mapping from npm audit severity (medium -> Medium, etc.) | Severity is dependent on the specific CVE found. |

| OSSF Scorecard | Repository score of each dependency | score <= 3.0 -> High score <= 6.0 -> Medium | |

| Malware Scanning | Malicious Detections | 2+ marked malicious -> Critical 1 marked malicious and 1+ marked suspicious -> High | Based on ratings of about 70 antivirus engines from VirusTotal. |

| Suspicious Detections | 2+ marked suspicious -> Medium | ||

| Sensitive Information leakage | Hardcoded Secrets (ggshield) | Any validated secret finding is assigned High risk. | LLM is used to filter false positives |

| Code Obfuscation | Unicode or Hexadecimal Encoding | Presence maps to Medium | |

| Long, Minified Lines | Presence maps to Medium | ||

| Control-Flow Flattening | Presence maps to High | e.g. detects while(true){switch(…)} evasion pattern | |

| High File Entropy | High Shannon entropy score indicates packed/encrypted code -> Medium | ||

| Network Communication Anomalies | Malicious Endpoint as per Virus Total | 2+ marked malicious -> Critical 1 marked malicious and 1+ marked suspicious -> High | LLM is used to filter out bogus endpoints before checking. |

| Suspicious Endpoint as per Virus Total | 2+ marked suspicious -> Medium | ||

| AST: Code Execution | Dynamic child_process | Presence maps to Critical | exec(variable) or spawn(variable) |

| Dynamic eval / Function | Presence maps to Critical | eval(variable) or new Function(variable) | |

| AST: Filesystem | Access to Sensitive Paths | Presence maps to High | e.g., fs.readFile(‘~/.ssh/id_rsa’) |

| AST: Webview XSS | innerHTML Assignment | Presence maps to High | e.g. element.innerHTML = variable |

| AST: Crypto | Hardcoded Encryption Key | Presence maps to High | e.g. createCipheriv(…, ‘static_key’,…) |

| Weak Cipher (e.g., DES) | Presence maps to High | e.g. createCipher(‘des’,…) |

In-Depth Automated Sandbox Policy Generation

The cornerstone of our solution is the automated generation of an accurate and least-privilege sandboxing policy. This is achieved through a hybrid analysis pipeline that combines high-speed code analysis with advanced semantic reasoning powered by LLMs.

Novel Methodology Overview

Our approach goes beyond traditional static analysis by combining four distinct components. Deterministic code analysis is used to systematically map function calls through AST traversal. This initial analysis is inspired by the HODOR system which constructs call graphs to record required system calls for Node.js applications28. Semantic understanding is incorporated via Large Language Models (LLMs), enabling the resolution of dynamically constructed behavior not easily captured by static techniques. The technique of combining AST-based resolution with LLM-driven reasoning has also shown to be effective in IRIS for inferring dynamic behaviors29. The pipeline also optimizes for context window constraints by minimizing irrelevant input and ensuring scalability to large codebases. The results are then refined with dynamic monitoring of extensions to get complete coverage. Finally, the results of all analyses are merged into enforceable sandbox rules without requiring manual intervention.

Step 1: Comprehensive Entrypoint Identification and Dependency Graphing

The analysis begins by identifying the extension’s primary and secondary entry points. This includes determining the main script from the package.json manifest30, inferring secondary entrypoints through activation events, and enumerating user-triggered commands and WebView or worker thread initializers.

A bundler, such as esbuild31, is then employed to construct a full dependency graph. The system is configured to perform a comprehensive analysis by starting at the extension’s main entry points and recursively following all import and require statements. This graph captures both first-party and third-party modules, as well as conditional and dynamic imports, resulting in a detailed metafile that enumerates every required Node.js core module and external dependency. In the rare case that the esbuild-based static pass fails or cannot produce a graph, the system emits an empty allow-list policy (i.e., no static grants). Execution then relies entirely on the dynamic analysis.

Step 2: Coarse-Grained Module Restriction with Security Baseline

To establish an initial security boundary, we first classify Node.js modules based on their inherent risk. Sensitive modules such as fs, http, and child_process are flagged due to their potential to perform input/ output, networking, or command execution.

In particular, we keep track of core Node.js modules based on their functionality. For file access, we keep track of the modules fs, fs/promises, path, and stream. For network access we keep track of http, https, http2, net, dgram, tls, dns, and url. For process execution we keep track of child_process and process. We also keep track of os which is in its own miscellaneous category. We choose to only keep track of the core Node.js modules for sensitive operations, as any third-party module that also executes such sensitive operations will eventually in its own source code use one of the core Node.js modules to perform the operation. Thus, protecting against the core Node.js modules is enough to protect against all modules including third-party ones. The modules detailed above aren’t a comprehensive list of the core Node.js modules that can perform the sensitive operations.

Any module not present in the extension’s dependency graph is disabled entirely in the generated sandbox policy. This approach reduces the attack surface, avoids false positives, and eliminates unnecessary runtime checks, therefore improving both security and performance.

Step 3: Fine-Grained Function Whitelisting via Advanced AST Analysis

To determine exactly which functions an extension uses within sensitive modules, we parse its codebase into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) using a tool such as Babel. The AST allows systematic traversal to identify all CallExpression nodes, enabling us to extract function usage patterns at a granular level.

Our analysis supports a variety of JavaScript ways of doing the same thing. It detects direct calls like fs.readFile(), as well as destructured assignments such as const { readFile } = require(‘fs’); readFile(). It also handles aliased references (const myRead = fs.readFile; myRead()) and method chaining patterns, including require(‘fs’).promises.readFile().

Dynamic property access, such as fs[method]() is also considered. If the method name can be resolved statically, it is included in the sandbox policy; otherwise, it is flagged for dynamic verification. Conditional imports, like const fs = condition ? require(‘fs’) : require(‘fs/promises’), are also fully analyzed to ensure coverage of all code paths.

The result is a whitelist of only those sensitive functions the extension actually uses. This whitelist is directly translated into enforcement rules, blocking access to any function not explicitly observed, while ensuring essential functionality is preserved.

Step 4: Hybrid Runtime Target Resolution: Large Language Models and Dynamic Profiling

The next aspect of our pipeline is resolving dynamic runtime behavior that traditional AST analysis cannot determine. To ensure comprehensive coverage for all extensions, we employ a dual-approach strategy.

LLM-Based Resolution

We use Large Language Models (LLMs) to perform semantic analysis that complements AST-based static techniques. For the majority of extensions, whose bundled first-party code is 2 megabytes or less, the bundled file is directly given to the LLM. For larger extensions, the code is broken up into 2 megabyte chunks so as to not surpass the LLM’s context window. Each of the chunks are treated to the following process and results are compiled at the end.

To reduce token usage and focus the model on core logic, we construct a lean version of the extension by stripping all third-party code under node_modules, preserving only the extension’s own source files.

This lean bundle is provided to the LLM with a structured prompt instructing it to act as a security auditor. The model is tasked with identifying sensitive runtime behaviors, including file system paths, network endpoints, and shell commands, especially those constructed dynamically. It returns these results in a structured JSON format, along with reasons that explain how each target was inferred from code context.

There are cases where the LLM fails due to being busy/unavailable. In all such cases, exponential backoff is used to retry the LLM requests. This allows the request to eventually go through. If there is total failure in LLM analysis, it isn’t fatal as the dynamic analysis follows and generates a sandboxing policy.

The LLM excels at resolving patterns traditionally hidden from static tools. It can infer configuration-based paths built from variables, constants, or user settings (e.g., path.join(os.homedir(), ‘.config’, extensionName)), reconstruct URLs composed from template literals or conditional logic, and identify command strings assembled from multiple sources. Additionally, it handles runtime branching logic, such as conditional execution paths or ternary expressions, and can trace deeply nested variable assignments or cross-function data flow. Studies confirm that advanced LLM models can analyze code and generate correct and detailed explanations to a reasonable accuracy as long as the code isn’t overly obfuscated32.

Beyond primitive resolution, the LLM also supports enhanced function-level analysis. In cases where static traversal cannot definitively resolve which sensitive functions are invoked due to aliasing, dynamic imports, or abstraction through utility layers, the LLM can inspect broader context and trace indirect references. For example, it can recognize that a function passed to executeShellCommand() eventually resolves to a call to child_process.exec(), even if obscured by layers of indirection or callback wrapping.

By incorporating this semantically-aware reasoning, the system can generate more complete and accurate whitelists of accessed resources and called operations. This reduces false negatives during enforcement and eliminates the need for overly permissive fallback policies. The LLM’s analysis thus plays a critical role in ensuring the sandbox enforces strict boundaries without disrupting legitimate functionality.

Dynamic Behavioral Baselining for All Extensions

To complement our AST and LLM based static analysis, and to account for limitations of AST and LLMs ability to accurately generate data flow graphs33, we implement a dynamic monitoring system for all extensions, regardless of their size. For all extensions, this dynamic baselining serves as a verification layer to confirm static analysis findings.

This process leverages the same in-process sandboxing architecture detailed in Section 4. However, during an initial monitoring period, the sandbox is configured for observation rather than enforcement. Instead of blocking operations, the proxy-based interception layer meticulously logs all interactions with sensitive Node.js modules.

Our system goes beyond simply recording that a function was called. By inspecting the parameters passed to each function at runtime, we can capture detailed operational data as specified below:

File System Access: We record the full paths of all files and directories the extension attempts to read, write, or modify.

Network Communication: We log the specific URLs and IP addresses of all outgoing network requests.

Process Execution: We capture the exact commands and arguments the extension attempts to execute.

This rich log of runtime behavior creates an empirical baseline of the extension’s behavior. After the monitoring period, this data is analyzed to automatically synthesize a precise, least-privilege sandbox policy. The sandbox then transitions to auto-enforcement mode where any action that falls outside the observed baseline is blocked by default. This ensures that even the largest and most complex extensions can be securely managed, providing a practical and robust solution.

Step 5: Intelligent Policy Synthesis

The final step in our solution is the intelligent synthesis of a comprehensive and enforceable sandbox policy, which is achieved by combining the findings from both our static and dynamic analyses. While each approach provides valuable insights individually, they work best together to create a sandbox policy that is both secure and functional.

This hybrid approach ensures maximum coverage and accuracy.

Dynamic analysis is crucial for capturing the core, day-to-day functionality of the extension. By monitoring the extension’s behavior during the observation period, we ensure that the functions and resources essential to the user’s typical workflow are permitted. This guarantees that the user’s experience is not interrupted by overly restrictive rules.

Static analysis, however, addresses an important gap left by dynamic monitoring as is similarly addressed in the Confine system34. A user is unlikely to access every single feature of an extension within the monitoring period. Static analysis examines the entire codebase, accounting for rarely accessed functionalities like annual update checking or obscure import/export features. By including these legitimate but infrequently used code paths in the sandbox policy, static analysis prevents them from being incorrectly blocked later, ensuring the extension remains fully functional in the long term.

The combined data from these two ways of analysis is then used for sandbox policy structure generation. The findings–the list of used modules, the whitelist of functions from both static and dynamic checks, and the LLM-resolved or dynamically observed paths and URLs–are merged into a single, structured sandbox policy file, typically in JSON format. This final policy document serves as a complete sandboxing policy file for the extension. It contains metadata about the analysis, rules to enable or disable entire modules, a granular list of permitted functions, and precise access control rules for file paths, network endpoints, and commands. This comprehensive sandbox policy becomes the rulebook for the sandboxing enforcement layer.

The generated sandbox policies support several advanced enforcement features to accommodate real-world extension behavior. These include pattern-based rules, allowing the specification of file paths and URLs using glob patterns or regular expressions for flexible yet bounded access control.

This automated, dual-analysis process results in policies that are both precisely tailored to the extension’s legitimate needs and maximally restrictive of potentially malicious behavior.

In-Depth Policy Enforcement Implementation

The enforcement of our auto-generated policies requires a sophisticated sandboxing architecture that operates within VS Code’s unique extension execution environment while maintaining compatibility and performance.

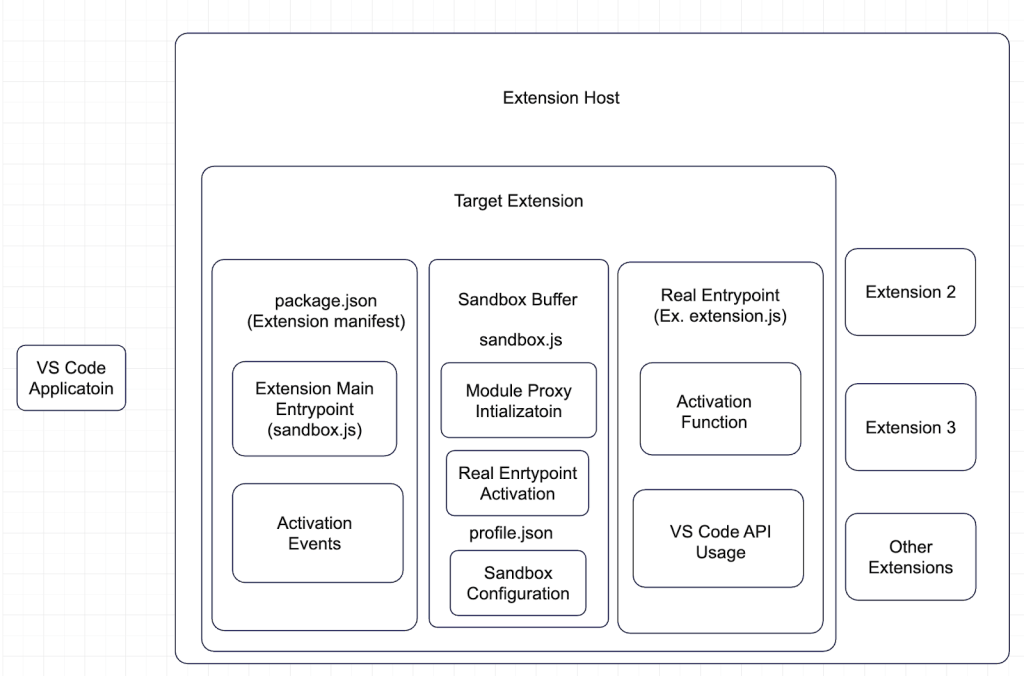

Understanding VS Code’s Extension Host Architecture

Below, we describe three core components that shape the constraints and affordances of any security mechanism implemented within this environment.

Extension Host Process:

VS Code runs extensions inside one or more dedicated Extension Host processes15, which are separate from the core renderer and main processes. Each Extension Host is an isolated Node.js runtime, responsible for executing extension code and facilitating communication with the main editor process via a JSON-RPC-like protocol. All extensions within the same host process share the same memory space and Node.js global state.

Extension Lifecycle:

The lifecycle of a Visual Studio Code extension begins with the loading of its manifest file (package.json), which declares metadata, activation events, and the entry point script. Upon meeting a specified activation condition–such as opening a file of a particular type, or executing a registered command–the Extension Host process instantiates the extension by importing its main module. This triggers execution of the extension’s activate() function, which registers all relevant commands, providers, and event handlers with the editor environment. From this point onward, the extension operates with full access to the Node.js runtime and its global APIs.

Shared Runtime Challenges:

VS Code’s extension architecture presents significant challenges for runtime isolation due to its shared execution model. All extensions within a single Extension Host process operate in the same Node.js runtime, sharing the global object space, module cache, and core API surface. The require() function and its associated module resolution cache are common across all extensions, which means that any modification to a core module, intentional or accidental, can affect every other extension loaded in the same process. Furthermore, global Node.js APIs such as fs, http, and child_process are not compartmentalized per extension and can be monkey-patched or proxied by any extension in the same Extension Host. This lack of strict module and global object isolation complicates the implementation of security boundaries, as extensions can potentially tamper with or eavesdrop on the behavior of others. Consequently, any sandboxing mechanism must not only confine a target extension’s access to sensitive resources but also defend against cross-extension influence within the shared runtime environment.

Extension-Scoped Sandboxing Requirements

Effective sandboxing within the VS Code Extension Host requires extension-scoped enforcement that confines only the target extension without impacting others. The system must apply restrictions selectively, allowing trusted extensions to operate normally while preventing sandboxed ones from bypassing controls via shared globals or indirect invocation. It must maintain runtime transparency, requiring no code changes by extension authors, and preserve compatibility with VS Code APIs and expected workflows. Security isolation must be robust, blocking unauthorized access to resources and preventing extensions from using others as proxies to circumvent restrictions. These constraints necessitate a finely scoped, low-overhead enforcement mechanism that integrates seamlessly with the shared Node.js runtime.

Our Novel In-Process Sandboxing Method

We implement a custom sandboxing architecture that operates entirely within the Node.js runtime. A foundational step in this process is the preemptive caching of pristine, original Node.js modules. Before any sandboxing hooks are installed, the sandbox loader script explicitly loads all sensitive modules (e.g., fs, https, child_process) and stores them in a private, static cache. This “clean cache” ensures that the sandbox’s enforcement layer always has a secure reference to the untampered, original module functionality, preventing any possibility of a sandboxed extension poisoning the module cache for other extensions or the sandbox itself.

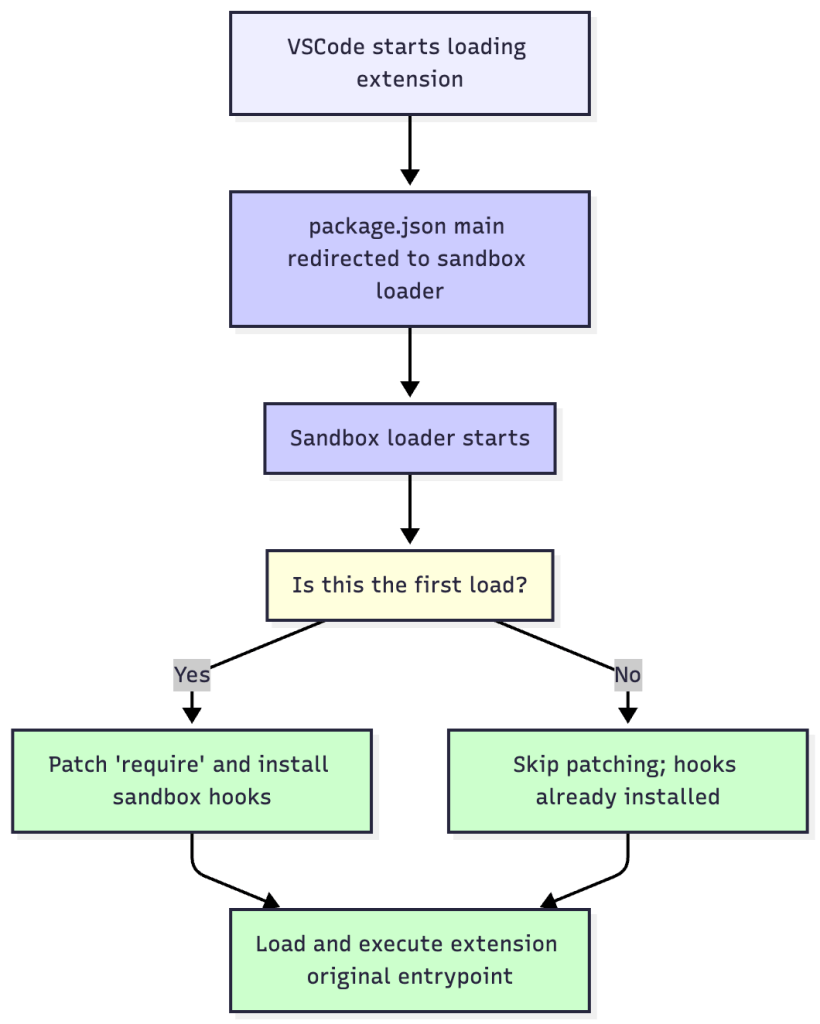

Extension Entry Point Redirection

The enforcement mechanism is initiated by cleanly redirecting how VS Code starts the extension. This involves programmatically modifying the extension’s package.json manifest file. The ‘main’ property, which normally points to the extension’s startup script, is changed to point to our custom sandbox loader script (sandbox.js). This loader becomes the first code to run when the extension is activated. Its job is to (1) access the clean cache of original modules, (2) install all necessary sandboxing hooks and patch require, and then (3) load and execute the extension’s original startup script, identified by a ‘realEntryPoint’ property we add to the manifest. This ensures the extension runs within the secured, policy-controlled environment from its first moment of execution. However, as other extensions in the Extension Host may have already been sandboxed, step (2) first checks whether the necessary hooks and patches have already been completed by another extension. If it has been, this step is skipped. This ensures there is no unnecessary duplication of hooks.

Dynamic Require Patching with Caller Verification

The core of the sandbox relies on a technique called dynamic require patching. The system intercepts Node.js’s fundamental require() function by overwriting Module.prototype.require. The custom interception logic is designed to be extension-scoped, which is achieved through a caller verification check. For every require() call, the function inspects the this.filename property available within the require function’s execution context. This property contains the absolute path of the script file making the call. The sandbox compares this callerPath against the sandboxed extension’s root directory path. If the caller is not within the extension’s directory, the call is considered to be from an external source (another extension or VS Code itself), and our hook immediately invokes the original, cached require() function, ensuring zero performance impact or interference. If the caller is verified to be part of the target extension, the policy enforcement logic proceeds. It first checks whether the module being invoked is a sensitive Node.js module that we want to control (ex. fs or https). If not, the original, cached module is returned. If yes, then the further logic proceeds.

Advanced Module Wrapping with Proxy-Based Interception

When a sandboxed extension’s require() call is granted access to a sensitive module, it does not receive the raw module from the clean cache. Instead, it is given a JavaScript Proxy object that acts as a secure intermediary. We utilize a generic proxy factory function which is configured with data-driven operation mappings. These mappings link specific function names (e.g., fs.readFile) to generalized operation categories (e.g., ‘file-read’). This allows for flexible and maintainable policy rules. This proxy-based wrapping is the mechanism that allows for function-level interception and argument inspection.

Resource-Specific Policy Enforcement

The policy enforcement logic implements a nuanced, two-tiered permission model. When an intercepted function is called (from an enforced extension as checked by this.filename), the system verifies whether the function call is allowed against the extension-specific sandboxing policy file (profile.json). It loads the policy file and then proceeds to the checks. The system first checks for highly specific action rules in the policy that match the operation category (e.g., an ‘allow’ rule for the ‘file-read’ operation). These rules can have filters that specify granular conditions, such as matching a path prefix. The system is designed to resolve dynamic, environment-specific paths by handling special filter types like extension-root (the absolute path to the extension) and home-relative (a path relative to the user’s home directory). If a matching action rule is found, its decision is final. If no specific action rule applies, the system falls back to the general module-config rule to determine if the entire module (e.g., fs) is enabled. This layered model provides both fine-grained control and broad, simple restrictions.

(when sandboxing technology is active in Extension Host)

Advanced Pattern Matching and Evasion Prevention

The system is secured with mechanisms to prevent extensions from bypassing the sandbox. This includes robust pattern matching that supports wildcards (glob patterns), allowing for flexible yet precise rules (e.g., allowing access to /workspace/project/*.json). Furthermore, it actively blocks common evasion tactics. For example, it overrides dangerous functions like eval(), which can execute arbitrary code, preventing them from being used within the sandboxed extension. It also intercepts other ways of accessing Node.js internals, such as module.createRequire, to ensure the extension cannot obtain an “un-proxied,” unsecured version of a sensitive module. A specific check is also included to deny the loading of native .node addons unless explicitly permitted by the sandboxing policy file, closing another potential vector for abuse.

Advantages of Our Implementation

Cross-Platform Compatibility: The sandboxing system is fully compatible with Windows, macOS, and Linux. It relies solely on Node.js runtime instrumentation, avoiding OS-specific sandbox primitives and ensuring consistent behavior across platforms and Node.js versions.

Fine-Grained Control: Enforcement operates at the function level rather than coarse module scopes. Policies support granular resource constraints, including per-file path and per-URL access controls, and can enforce context-aware rules based on usage patterns.

Performance Optimization: For unrestricted extensions, sandbox logic is bypassed entirely via caller verification. Policy checks use lazy evaluation, minimizing overhead. Enforcement hooks are applied only where needed, avoiding global performance penalties.

Developer-Friendly: Policy violations trigger clear, actionable error messages. Detailed logs are emitted to aid debugging. Extension authors can refine or override policies without modifying extension code, streamlining secure development workflows.

Security Robustness: The system defends against common evasion techniques, including eval(), module.createRequire, and native .node addon loading. Clean module caching prevents cross-extension tampering. Enforcement is resilient within a shared runtime, maintaining isolation boundaries under adversarial conditions.

This implementation successfully addresses the unique challenges of sandboxing extensions within VS Code’s shared runtime while maintaining the flexibility and precision required for practical deployment.

Specific Implementation Details

The code for the full implementation of risk profiling (step 1) can be found at: github.com/Shadow-Ninja1/Risk-Profiling-Extensions

The following section details the methodology for policy generation and enforcement in our sandboxing system (steps 2 and 3). At a high level, the system constructs two JavaScript bundles and a build graph, infers reachable platform capabilities, maps concrete function calls, augments static findings with large language model (LLM) analysis, and finally assembles a policy that combines global options, category grants, and explicit per-function allowances.

Policy Generation

The process begins by locating the extension’s entry point (main) from package.json and producing two esbuild artifacts alongside a build metadata file. We invoke esbuild to generate a “full” bundle that preserves Node.js dependencies while excluding the VS Code host APIs (npx esbuild “<entry>” –bundle –platform=node –metafile=”meta.json” –outfile=”full-bundle.js” –external:vscode –sourcemap) and a “short” bundle that aggressively externalizes all imports (npx esbuild “<entry>” –bundle –platform=node –outfile=”short-bundle.js” –external:’*’ –sourcemap). The esbuild meta.json file captures a comprehensive build graph that is subsequently parsed to recover import relationships.

To identify which Node.js core modules are actually reachable from the extension, we parse meta.json and inspect meta.outputs[*].imports[*], collecting the path of each import (for example, fs, fs/promises, or http) while also recording whether esbuild marked it as external. We normalize any node:-prefixed specifiers (for example, node:fs to fs) and form the union of import specifiers across all outputs. Intersecting this set with a fixed allowlist of core modules–namely fs, fs/promises, path, stream, os, process, http, https, net, dgram, tls, dns, and child_process–filters out host APIs such as vscode (which are also externalized) and all third-party packages. The resulting inventory constitutes a baseline of reachable built-ins that seeds the module-level portion of the sandbox policy; a later pass refines this baseline at the function level.

We next construct a static call map over the bundles using @babel/parser and @babel/traverse. Parsing the emitted code enables us to enumerate concrete invocations such as fs.readFileSync or child_process.spawn, including three common patterns: member calls on module aliases (e.g., const cp = require(‘child_process’); cp.spawn(…)), direct calls to destructured imports (e.g., const { spawn } = require(‘child_process’); spawn(…)), and namespace member calls (e.g., fs.readFileSync(…)). For each occurrence we record a mapping of the form { “<module>.<function>”: [lineNumbers…] }. This call map is later used to emit explicit function-level allowances in cases where coarse-grained category permissions are too broad or inapplicable.

We complement static analysis with LLM-based inference over a compact bundle. When the bundle exceeds 2 MB, it is partitioned into contiguous chunks of at most 2 MB; each chunk is analyzed independently and the results are merged. The analysis prompt positions the model as “an expert security agent performing static analysis for sandbox policy generation” and directs it to track usage of key modules (fs, http, https, child_process, net, dns, os) as well as high-risk VS Code APIs (e.g., workspace.fs.writeFile, tasks.executeTask, window.createTerminal, env.openExternal, commands.executeCommand, and env.clipboard.*). The model is asked to return a strictly structured JSON containing (i) moduleUsage: a per-module list of functions and observed parameter structures, including a vscode section for editor APIs; (ii) filePaths: paths rooted in home, workspace, install, temporary, or OS root directories; (iii) networkPaths: URLs or socket endpoints; and (iv) processes: stringified command lines. Merging follows a conservative union strategy: arrays such as filePaths, networkPaths, and processes are de-duplicated and concatenated, while moduleUsage is merged by module name with lists appended.

Then we conduct dynamic analysis over the dynamic monitoring period. Dynamic analysis is performed in the same way as the sandboxing enforcement detailed in 5.3, except all function calls are allowed to pass through regardless of the policy. Instead, the calls and their parameters are logged in a .txt file in the local extension directory. This allows all function calls to be recorded as well as all the file paths, network endpoint, and process executions which are parameters of a limited set of function calls.

Finally, we assemble a profile.json policy by combining the static call map, the LLM outputs, and the logging from the dynamic monitoring. The resulting profile encodes global options, per-module entries, and category-level grants with filters (e.g., restricting file access to observed directories or network access to enumerated domains). Where category grants would be overly permissive, the system emits explicit function allowances derived from the static call map (e.g., authorizing child_process.spawn without enabling unrelated child_process capabilities). This layered construction yields a principle-of-least-privilege policy that is specific enough to reduce attack surface while remaining faithful to the extension’s observed behavior.

Our implementation targets a Node.js runtime and depends on a set of tooling installed at the project root: esbuild, prettier, @babel/parser, @babel/traverse, source-map, @anthropic-ai/sdk (~ 0.22.0), axios (~ 1.7.2) with axios-retry (~ 4.4.0), dotenv (~ 16.4.5), fs-extra (~ 11.2.0), pino (~ 9.2.0) with pino-pretty (~ 11.2.1), unzipper (~ 0.11.6), and yargs (~ 17.7.2). For LLM inference we employ Gemini-2.5-flash and Anthropic Claude 3.5 Sonnet (claude-3-5-sonnet-20240620). These components collectively support reproducible builds, precise static analysis, robust result merging, and deterministic policy synthesis.

Policy Assembly

Policies are serialized to profile.json that has the following example format:

| { { “type”: “option”, “name”: “log-level”, “value”: “verbose” }, { “type”: “action”, “action”: “allow”, “operation”: “file-read”, “filters”: [ { “type”: “path-prefix”, “value”: { “type”: “extension-root” } }, { “type”: “path-prefix”, “value”: { “type”: “home-relative”, “path”: “.gitconfig” } } ] }, { “type”: “action”, “action”: “allow”, “operation”: “file-write”, “filters”: [ { “type”: “path-prefix”, “value”: { “type”: “home-relative”, “path”: “.dev-assistant/cache/” } } ] }, { “type”: “action”, “action”: “allow”, “operation”: “network-outbound”, “filters”: [ { “type”: “remote-host”, “value”: “api.github.com” } ] }, { “type”: “action”, “action”: “allow”, “operation”: “dns-resolve”, “filters”: [ { “type”: “remote-host”, “value”: “api.github.com” } ] }, { “type”: “action”, “action”: “allow”, “operation”: “process-exec”, “filters”: [ { “type”: “process-name”, “value”: “git” } ] }, { “type”: “module-config”, “module”: “dgram”, “enabled”: false }, { “type”: “module-config”, “module”: “http2”, “enabled”: false }, { “type”: “action”, “action”: “deny”, “operation”: “load-native-addon” }, { “type”: “function”, “name”: “fs.readFileSync”, “allow”: false }, { “type”: “function”, “name”: “fs.writeFileSync”, “allow”: false } } |

Sandbox Enforcement

Bootstrapping and Scope

At startup, the extension’s package.json is rewritten so that “main” points to a loader, sandbox.js. The loader preserves the original entry point in realEntryPoint, reads the sandbox configuration from profile.json, installs the runtime interception hooks, and only then invokes the original program by issuing require(realEntryPoint). Scope is enforced by resolving the caller’s filename at each require() and checking whether it lies under the extension root–concretely, via this.filename.startsWith(extensionRoot). Only modules whose load site originates within the extension’s own directory tree (including its co-located node_modules/) are subject to sandboxing. Loads initiated outside this tree–e.g., by external tools or parent processes–bypass the sandbox, ensuring that the enforcement domain is limited to the extension and its private dependency closure.

Hooking Coverage

The system wraps Module.prototype.require so that lookups for covered modules return Proxy objects that mediate sensitive operations; unrecognized modules defer to the original resolver and execute unmodified. Coverage explicitly includes the Node.js core surfaces fs, fs/promises, http, https, http2, net, tls, dns, path, os, process, and readline, and additionally inspects attempts to load native add-ons (.node binaries).

Operations are mapped as follows. File system calls–across both fs and fs/promises–are classified as file-read or file-write, extracting the target path by applying path.resolve(args[0]). Outbound HTTP(S) activity (http, https) is mapped to network-outbound, with the destination host derived from either a URL string or an options object’s {hostname|host} field. Socket-level activity via net and tls is mapped to both network-outbound (client) and network-inbound (server), again extracting {host|hostname} as the peer identifier. Name-resolution via dns yields dns-resolve for lookup, the resolve* family, and reverse. Process creation via child_process is normalized to process-exec across spawn, exec, fork, and related APIs, recording the executable name from the first argument. By contrast, http2, path, os, process, and readline are proxied without an intrinsic operation label; access control for these modules is governed exclusively by function-specific, module-level, or global rules. Loading native add-ons is denied by default and succeeds only if the policy explicitly grants load-native-addon.

Policy Evaluation and Precendence

For each intercepted invocation, the proxy constructs a decision tuple (module, operation, details) and queries isAllowed(module, operation, details). Authorization proceeds in fail-close order. First, a hardcoded exception permits the extension to read and write its own files: if operation ∈ {file-read, file-write} and details.path is under extensionRoot, the call is allowed. Second, function-specific rules are consulted using exact descriptors (e.g., “fs.readFileSync”); an explicit allow or deny takes immediate effect. Third, category (operation) rules are evaluated–if the rule’s filters match (see 5.3.4), its configured allow/deny applies. Fourth, module-level rules of the form “type”:”module”,”descriptor”:”<name>” are applied. Fifth, global rules (“type”:”global”,”descriptor”:”system”) provide installation-wide defaults. If none of the above match, the system denies by default. Denials throw a namespaced error (e.g., Error(“SANDBOX: …”)); for Promise-based APIs such as fs/promises, the proxy rejects the Promise with the same error. Independently of access decisions, logging is controlled by a verbosity option (quiet or verbose) and emitted to logging.txt using the original fs bindings, ensuring that audit trails are never blocked by the sandbox.

Filter Semantics for Category Rules

Category rules may carry zero or more filters; when no filters are present, the rule applies unconditionally. If filters are specified, the system uses disjunctive (OR) semantics: any single matching filter is sufficient to trigger the rule. The following filter types are supported. A path-prefix filter may be a literal absolute string, matched via startsWith(resolvedValue), or a special path object. Special objects include { “type”: “extension-root” }, which resolves to extensionRoot, and { “type”: “home-relative”, “path”: “<suffix>” }, which resolves to path.join(os.homedir(), suffix). A remote-host filter performs an exact string comparison against details.host extracted from URLs or options; ports and subdomains are not pattern-matched. Finally, a process-name filter compares exactly against the executable name (e.g., “node”, “git”, “npm”). Together, these filters allow policies to express least-privilege constraints that are specific yet mechanically checkable at call time.

Results & Discussion

Real-World Application and Validation

To validate our solution’s effectiveness, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of the VS Code extension ecosystem and tested our sandboxing implementation across a diverse set of real-world extensions.

Current Security Landscape Analysis

To evaluate the effectiveness of our sandboxing solution, we performed a comprehensive empirical study across two axes: a large-scale analysis of the extension ecosystem and targeted deployment of our sandboxing system on high-risk extensions.

Ecosystem-Level Risk Profiling

From a sample of 1500 extensions, we determined the following characteristics about VS Code extensions in terms of the total Javascript/ Typescripts files sizes in an extension.

| Total Extension JS/TS File Size | Percent of Extensions |

| 0 megabytes | 22.19% |

| Between 0 and 2 megabytes | 61.99% |

| 2 or more megabytes | 15.82% |

This survey shows that a majority of the extensions can pass through the LLM portion of the static analysis with only one pass while 15.82% would require more than one pass. This validates that the 2 megabytes chunking restriction isn’t overly restrictive and is reasonable for the current state of VS Code extensions.

We analyzed 377 top trending VS Code extensions to assess publisher trustworthiness, permission exposure, dependency hygiene, and behavioral red flags. The trending criteria was utilized as it provided key benefits: the extensions analyzed were being used by the current VS Code population and the extensions had a wide range of popularity from tens of downloads to many thousands so our analysis is less biased towards popular/unpopular extensions.

| Category | Metric | Count (%) |

| Publisher Type | Verified Publishers | 26 (6.9%) |

| Unverified Publishers | 351 (93.1%) | |

| Maintenance Status | Active (updated <6 months) | 323 (85.7%) |

| Stale (6-24 months) | 10 (2.7%) | |

| Abandoned (>24 months) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Permission Usage | Broad File System Access | 330 (87.5%) |

| Network Communication | 17 (4.5%) | |

| Process Execution | 67 (17.8.5%) | |

| ≥2 High-Risk Permissions | 75 (19.9%) |

Supply Chain Security Findings

| Category | Metric | Value |

| Dependency Count | Total Unique Packages | 1,772 |

| Extensions with 0-5 Dependencies | 323 (85.7%) | |

| 6-20 Dependencies | 31 (8.2%) | |

| 21-50 Dependencies | 9 (2.4%) | |

| >50 Dependencies | 14 (3.7%) | |

| Vulnerabilities | Extensions with Known CVEs | 23 (6.1%) |

| High Severity CVEs | 10 | |

| Medium Severity CVEs | 15 | |

| Low Severity CVEs | 0 | |

| Outdated Dependencies (>2 years) | 45 (22.5%) | |

| Dependencies with Advisories | 23 (11.5%) |

Malicious Behavior Indicators

| Malicious Pattern | Count | Criteria Summary |

| Suspicious Network Activity | 17 (4.5%) | Undocumented API endpoints, Data transmission without user consent, Connections to suspicious domains |

| Obfuscated Code Pattern | 0 | Extreme minification beyond normal optimization, Dynamic code generation patterns, Anti-analysis techniques |

| Privilege Escalation Attempt | 14 (3.7%) | Unauthorized system configuration access, Attempts to modify VS Code’s internal files, Persistence mechanism establishment |

| Data Exfiltration Pattern | 19 (5%) | Environment variable harvesting, User credential collection attempts, Workspace content transmission |

Risk Classification Results

| Risk Tier | Count | Criteria Summary |

| Critical-Risk | 43 (11.4%) | Connections to malicious domains, flagged by VirusTotal as malware, or malicious patterns |

| Highly vulnerable, but not malicious | 100 (26.5%) | Broad permissions with legitimate use cases, vulnerable dependencies but core functionality valuable, suspicious patterns but unclear malicious intent |

| Medium-Risk | 234 (62.1%) | Limited permissions with some security concerns, outdated but not vulnerable dependencies |

| Low-Risk | 0 | Simple, well-scoped, and well-maintained |

These results are evidence of the scope of the problem as extensions with significant vulnerabilities and potential malicious activity are common. Sandboxing extensions during runtime will be important to ensuring users can code in a safe development environment.

Sandboxing Implementation Results

We analyzed the 25 most recent trending extensions and implemented our automated sandboxing system. In addition to this, we conducted dynamic analysis on all of them to understand how our static tests compared to the dynamic testing.

Policy Generation Success Rates

| Metric | Count | Percentage |

| Successful Automated Policies | 23 | 92.0% |

| Manual Refinement Required | 2 | 8.0% |

| Policy Generation Failures | 0 | 0.0% |

Note: Manual refinement was required due to esbuild bundling errors (not sandboxing limitations) which was resolved by explicitly externalizing certain third-party modules that esbuild could not resolve.

| Policy Complexity | # Extensions | Percentage |

| Simple (1-5 rules) | 9 | 36.0% |

| Medium (6-15 rules) | 9 | 36.0% |

| Complex (16+ rules) | 7 | 28.0% |

Comparative Analysis of Static vs. Dynamic Function Call Detection

To evaluate the effectiveness of static analysis in capturing extension behaviors, we conducted a controlled experiment comparing the function calls identified through our automated static pipeline (LLMs and ASTs) against those revealed via dynamic observation. All 25 extensions were installed in a logging-only sandbox mode. We manually interacted with each extension, exercising all available functionality through UI elements, registered commands, and context menu options. The system logged all function calls during this simulated usage session.

The results of this comparative analysis are summarized in the table below:

| Detection Method | Average % of Function Calls Identified |

| Detected by Both Methods | 44.97% |

| Static Analysis Only | 50.90% |

| Dynamic Analysis Only | 4.13% |

These findings demonstrate that static analysis alone captures the majority of required function calls, including many not exercised during typical manual usage. In contrast, dynamic analysis primarily identified function calls related to core functionality. However, it also revealed a small but critical set of behaviors (4.13%) that were absent from the static view. These typically involved runtime-dependent execution paths, such as delayed feature activation or conditional command execution.

The complementary nature of these techniques validates our hybrid approach. Static analysis ensures broad behavioral coverage, including edge cases and infrequently used paths, while dynamic analysis guarantees correctness for runtime-critical operations. The combined strategy results in policies that are both secure and functionally complete.

The following table provides a further breakdown of the capabilities of LLMs compared to ASTs in the function call detection:

| Detection Method | Average % of Function Calls Identified |

| Detected by Both Methods | 30.78% |

| AST Only | 20.26% |

| LLM Only | 48.96% |

This shows that LLMs and ASTs are both important when detecting the function calls an extension executes. However, LLM’s do detect a greater proportion of the function calls.

Sandboxing Enforcement Results

To evaluate runtime compatibility under enforcement, all 25 extensions were tested using the auto-generated sandbox policies. Each extension was adapted to log failures and then check the completeness of the statically created policy.

Out of the 25 extensions, 16 executed successfully without any modifications, indicating full compatibility with their statically generated policies. An additional 2 extensions required only minor policy adjustments, limited to modifying the list of permitted function calls (which is handled through dynamic monitoring). The remaining 7 extensions exhibited runtime failures due to incomplete policy coverage (also mitigated through dynamic monitoring).

A breakdown of the failure causes, is summarized in the following table:

| Failure Category | Number of Extensions |

| Insufficient Function Call Configuration | 7 |

| Insufficient File Path Configuration | 5 |

| Insufficient Network Configuration | 2 |

| Insufficient Process Configuration | 4 |

These categories are not mutually exclusive; some extensions have multiple causes of failure.

The detection of the file paths, networks , and processes in the table above were done solely through the use of LLMs, not ASTs or dynamic monitoring. Its analysis identified all file path accesses for 80% of extensions, all network connections for 92% of extensions, and all process executions for 84% of extensions. These numbers highlight the LLMs’ aptitude in these specific but crucial parts of extension sandboxing.

However, the fact remains that of the 25 tested extensions, 9 failed during runtime when enforced under statically derived policies, while 16 succeeded without modification. For example, one extension attempted to connect to www.google.com, but the connection was blocked due to a missing endpoint rule in the static policy.

Other observed failure modes included inadequate detection of child-process invocations—such as calls to “php,” “osascript,” and “which”—which impeded accurate coverage of process-execution behavior; omission of user-driven, custom network destinations and missed identification of connections to local ports, leading to either over-permissive or over-restrictive network controls; and inability to resolve salient file-path placeholders (for example, the Yarn directory), which produced mismatches between intended path-scoped permissions and their runtime evaluation. Collectively, these deficiencies reduced the precision of enforcement, increasing both false denials and unguarded behaviors.

These results reinforce the necessity of hybrid policy generation. The observe-only dynamic monitoring phase is specifically designed to address such deficiencies: extensions that fail under static policies can be monitored over a 7-day period to empirically capture and integrate missing behaviors into an updated, least-privilege policy. This ensures future enforcement will succeed without manual intervention. With the two approaches together, a comprehensive and reliable sandboxing configuration can be achieved for all extensions.

All compatibility issues observed were due to under-permissive policies–not problems with the architecture–confirming that the sandboxing system is both feasible and resilient when applied to real-world VS Code extensions.

In addition, there were no noticeable impacts or changes on the functionality of the extensions when the sandbox was implemented successfully. This means that the extensions can be used as normal and users do not need to worry about performance impacts in terms of additional time delay. This is essential as it highlights its non-intrusive behavior in a development environment which is important for an effective cybersecurity product.

Unique Contributions Revisited

This research delivers several distinct contributions to the field of VS Code extension security:

Novel Methodological Contributions

The core methodology contributed is a hybrid static–dynamic analysis pipeline that merges traditional AST traversal and LLM-powered analysis with dynamic behavioral monitoring. This approach allows the system to resolve all extension behavior, including behavior that rarely gets executed during extension usage, while still making sure all essential functionality stays intact.

Building on this foundation, the system also introduces an automated least-privilege policy generation mechanism. It transitions beyond conventional, coarse-grained permission models by inferring function-level access rules across file system, network, and subprocess domains. Once permissions are extracted using the static-dynamic module, they are formed into actionable sandboxing policies.

Technical Innovations

The enforcement layer presents a novel in-process, extension-scoped sandboxing model. Unlike traditional sandboxing systems that operate at the OS level, this design addresses the unique constraints of VS Code’s shared runtime by applying enforcement selectively at the extension level. It introduces a caller verification mechanism, preventing interference with other extensions in the same process.

To support threat triage, we also contribute a multi-layered risk assessment solution. This system combines metadata evaluation, supply chain analysis, and behavior heuristics to generate per-extension risk scores. Importantly, the solution incorporates malicious behavior patterns specifically for extensions, such as suspicious activation events or credential handling anomalies, and classifies extension risk in a way that informs policy enforcement later on.

Practical Impact

Our solution enables secure usage of powerful yet high-risk extensions that would otherwise be disallowed under binary allow/deny policies. By allowing sandboxed execution with fine-grained restrictions, organizations can adopt critical and helpful tooling without sacrificing security. Furthermore, developers gain visibility into their extension’s operational needs, encouraging adherence to least-privilege principles and reducing unneeded overreach.

From a professional work environment standpoint, this system addresses key hurdles for VS Code adoption in regulated environments. It offers centralized policy control and even potential customization of the policies–both essential for compliance with security measures by companies. The solution thus works at an organizational scale, enabling security teams to balance helpfulness with risk mitigation.

Limitations

While the proposed methods offer important advancements in securing the VS Code extension ecosystem, it is not without limitations. These fall into four primary categories: technical constraints, deployment challenges, scope limitations, and research boundaries.

Technical Limitations

Static analysis remains fundamentally constrained when analyzing extensions that rely heavily on runtime-generated code, or dynamic imports. These patterns obscure control flow and hinder accurate permission inference. Additionally, obfuscation techniques such as string encoding minification or domain-specific encryption layers can further limit the precision of AST-based analysis and LLM interpretation. Similarly, dynamically loaded dependencies that are not present in the bundle at analysis time may bypass inspection altogether.

The LLM-based system, while effective, introduces its own challenges. Its accuracy depends on the model’s capability to understand complex code structures that require context, which can vary across LLM versions. LLMs are also prone to recommending over-permissive policies if not tightly assessed. Moreover, token usage and thus cost scale with extension size, posing potential barriers for large extensions or frequent reanalysis.

During the dynamic monitoring phase, large extensions operate in a logging-only mode, without active enforcement. This introduces a time period during which malicious behavior could occur, though logging will still record such behavior.

At runtime, the sandbox cannot defend against all methods available in Node.js, especially those exploiting unpatched vulnerabilities/intentional bypasses available in the VS Code API (those however can be disabled if desired). Furthermore, for extensions that have very frequent functions called, the overhead from proxy-based enforcement may cause measurable performance degradation.

Deployment Challenges

While most extensions operate correctly under enforced policies, certain classes of extensions may require manual refinement. These typically include those that rely on undocumented APIs or have minified function calls or imports. In such cases, static policy generation may fail to capture full behavior coverage, resulting in compatibility issues.

As extensions evolve, their functionality may change, necessitating updates to the sandbox policy. This means maintenance is needed, especially in places where hundreds of extensions are in use.

Scope Limitations

The current implementation primarily targets extensions written in JavaScript or TypeScript and executed in the Node.js runtime. It does not yet support WebView-based extension components, which operate in separate browser contexts and follow different security models. WebView components embedded in extensions have had sandbox escapes and unauthorized access to the Node.js context in prior attacks35. The solution also does not address potential vulnerabilities or insecure defaults in VS Code’s core extension APIs themselves, focusing instead on extension behavior. Also, the system does not defend against attacks targeting VS Code IDE directly.

Research Limitations

The risk profiling evaluation conducted was limited to a sample set of 377 extensions, which–while representative of trending extensions at the time of the study–may not capture the full diversity of the ecosystem. For example, it may introduce bias towards extensions with more popular topics–these limitations can be addressed in the future by taking a larger random sample of extensions. Additionally, the test period was limited and may not reflect long-term usage patterns.

In addition, the full static and dynamic testing was conducted on a sample size of 25 extensions, which may be too small to fully evaluate the system’s effectiveness in policy generation and enforcement.

Future Directions

System Adaptability

During policy-enforcement mode, only operations allowed by the policy execute; all others are blocked and the denial is logged. As an enhancement, the system can prompt the developer asking whether they want to approve a blocked operation. It will include context on the command and its specific parameters. If approved, the system updates the policy to reflect the change. In addition to allowing developers to customize the system should they find the need, this allows the system to easily adapt to any update the extension receives during the enforcement period.

Currently the system focuses on the generation and enforcement of the sandboxing policy. The security analysis of the generated policy (e.g. developing heuristic rules for which file paths are safe vs unsafe and allowing the user to view, verify, and modify) can help verify malicious behavior is not permitted by the policy.

Enhanced Analysis Capabilities

Future work will improve static analysis precision through taint-sink tracking, which could be implemented through CodeQL rules. By identifying sensitive function calls as sinks and tracing their inputs to specific code slices (taints), we can reduce token usage in LLM prompts, improve analysis speed, and enhance policy accuracy. This enables handling of larger and more complex extensions efficiently.

References

- E. Lin, I. Koishybayev, T. Dunlap, W. Enck, A. Kapravelos. UntrustIDE: exploiting weaknesses in VS code extensions. https://www.ndss-symposium.org/wp-content/uploads/2024-73-paper.pdf (2024). [↩] [↩]

- S. Edirimannage, C. Elvitigala, A. K. K. Don, W. Daluwatta, P. Wijesekara, I. Khalil. Developers are victims too: a comprehensive analysis of the VS code extension ecosystem. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2411.07479v1 (2024). [↩]

- S. Iyer. Security and trust in visual studio marketplace. https://devblogs.microsoft.com/blog/security-and-trust-in-visual-studio-marketplace (2025). [↩]

- Y. Liu, C. Tantithamthavorn, L. Li. Protect your secrets: understanding and measuring data exposure in VSCode extensions. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2412.00707 (2024). [↩]