Abstract

Genomic variations play a crucial role in determining disease susceptibility, and even small mutations can alter protein structure and cellular function. Unlike traditional experimental methods, this study uses an innovative computational approach to investigate genetic variants from human exome sequencing data, focusing on the HNF1A gene mutation associated with maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY3). Using data from the 1,000 Genomes Project (sample SRR701471), we aligned sequences with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA), performed genotyping with SAMtools mpileup, and annotated variants using ANNOVAR, all on Midway3, a supercomputer at the University of Chicago. From over 112,000 high-quality variants, we identified 15 disease-annotated mutations, including a missense variant in HNF1A (serine to glycine). Protein modeling with AlphaFold and visualization in Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) revealed that this substitution causes a structural displacement of 18.34 Å between α-helices. This study demonstrates a computational workflow for variant identification and structural modeling, while highlighting the critical need for database validation. The HNF1A variant identified (rs1169305) was subsequently confirmed as a common benign polymorphism, underscoring that computational predictions must be validated against clinical databases before drawing pathogenicity conclusions. Although the computational confidence of this study is moderate, this approach highlights the power of genomic annotation and protein modeling in understanding disease mechanisms and guiding personalized treatment strategies for MODY3.

Keywords: computational genomics, HNF1A mutation, MODY3, exome sequencing, variant annotation, protein modeling, personalized medicine

Introduction

In cellular regulation, form is essential. Cellular regulation ensures that a cell maintains its proper form and function; shifts undetectable even by the world’s most powerful microscopes in proteins, signaling pathways, or gene expression can disrupt this balance, ultimately leading to disease. Traditional biological experiments, such as gene cloning, PCR, Western blotting, and X-ray crystallography, are time-consuming, expensive, and limited in scale, making them unsuitable for analyzing the vast datasets generated by modern high-throughput sequencing. By integrating computer science, mathematics, and statistics, computational biology has become a powerful tool that has transformed our understanding of biology and disease. This study applies a computational approach to investigating a human’s genomic information and their genetic diseases. Our approach exemplifies the revolutionary concept of personal genomics, which involves analyzing an individual’s genetic makeup to gain a deeper understanding of their health and potential risks. We employed exome sequencing techniques1, which provide confident data by targeting protein-coding regions. This technique uses new sequence technology that chooses DNA fragments complementary to known exonic sequences and focuses on the 1%–2% of the genome where 85% of disease-causing mutations occur.

The sample analyzed (SRR701471) is from the 1,000 Genomes Project2’3, a population genetics resource containing healthy individuals from diverse ethnic backgrounds. The provided patient exhibits 120,000 raw variations in their entire genome, and we chose to investigate one variation for in-depth analysis. This paper focuses on the mutation in the HNF1A gene4, a transcription factor that is crucial for pancreatic β-cell function. Mutations in HNF1A are known to cause maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 (MODY3)5’6, a disease sensitive to sulfonylureas. We investigated this gene through alignment, genotyping, and annotation to determine how the gene functions, to identify the mutation, and to understand its impact on individuals. It is essential to note that the presence of an HNF1A variant in population databases does not confirm disease expression. The individual sequenced (SRR701471) is from a healthy population cohort and may not exhibit MODY3 phenotype.

Methodology

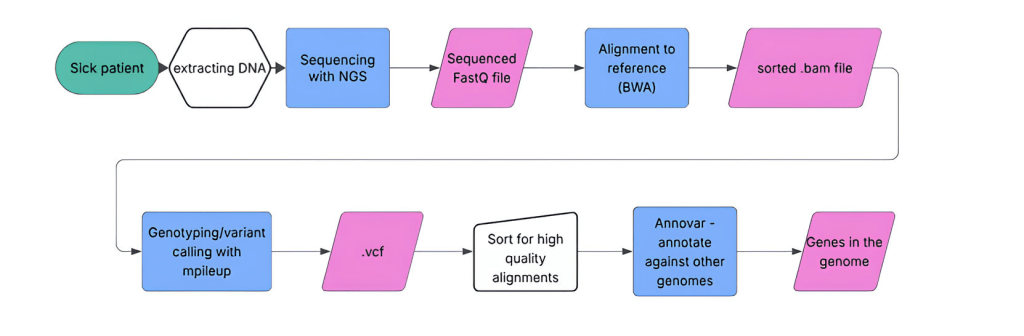

We analyzed genomic sequencing data from sample SRR701471, a healthy control individual from the 1,000 Genomes Project, on a high-performance computing cluster (Midway3)7 hosted by the UChicago Research Computing Center (RCC). We applied the following steps in our research:

- Obtain Data

- FASTQ files are typically used to store raw sequencing reads, and they contain both the nucleotide sequences and the quality scores that indicate the confidence of each base. The genome was delegated to us as two FASTQ8 files (SRR701471_1.fastq and SRR701471_2.fastq). SRR701471_1.fastq contained the forward read, while SRR701471_2.fastq contained the reverse read.

- DNA and RNA Sequences Alignment

We utilized Burrows-Wheeler Aligner version 0.7.17-r1188 (BWA)9, a software package for aligning short DNA and RNA sequences10, to map sequencing reads to a reference genome database, such as the Human Genome Project reference. This software first creates an FM-index of the reference genome, which is based on the Burrows-Wheeler Transform, and then uses this index to map the reads quickly and efficiently. BWA has three main algorithms: BWA-backtrack, BWA-SW, and BWA-MEM. We used BWA-backtrack to identify the optimal placement of each read and to account for matches, mismatches, and gaps relative to the reference genome, reflecting the standard pipeline used for short-read data in the 1000 Genomes Project. The primary output of the BWA is a file in the Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) format. - Variant Identification and Genotyping

We employed mpileup version 1.611 for genotyping, which generates base-level quality scores for each nucleotide in the sequence. This tool assesses the sequence alignment data file, evaluates the sequencing coverage at every base position, and calculates Phred quality scores12’13, which quantify the probability that a given base is incorrectly called. Higher Phred scores correspond to greater confidence in the accuracy of the base call. These scores assess whether a particular nucleotide is reliable for downstream analyses, such as variant identification and genotyping. The outputs are variant call format (VCF) files used in genomics to store genetic variation data. - Variant Quality Control and Filtering

Following alignment with BWA-backtrack and variant calling with SAMtools mpileup, we applied quality filtering based on Phred scores. Variants with Phred quality scores >50 were retained, corresponding to >99.999% base-calling confidence because we chose to prioritize specificity (confidence) over sensitivity (variant yield), since 3D protein modeling of HNF1A required exceptionally accurate variant identification. This filtering reduced 156,432 raw variant calls to 112,076 high-confidence variants. Subsequent ANNOVAR annotation identified 14,719 variants in exonic regions. We did not apply any other filtering methods since the high Phred threshold already ensured exceptional base-calling quality, and visual inspection of coverage in IGV confirmed adequate depth across analyzed regions. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing was not applicable as this analysis examined a single individual rather than a population.

- Sequence Annotation

Genetic variant annotation (ANNOVAR)14, downloaded March 2023,was used to process the variant call format (VCF) files. ANNOVAR is an efficient software tool that functionally annotates genetic variants from significant amounts of sequencing data produced from high-throughput sequencing platforms. This tool converts the VCF file into ANNOVAR’s input format and annotates the variants using multiple reference databases. Annotations include known variants, allele frequency information, and pathogenic mutations. Figure 1 offers a concise overview of our workflow that we utilized to analyze this person’s genome.

Results

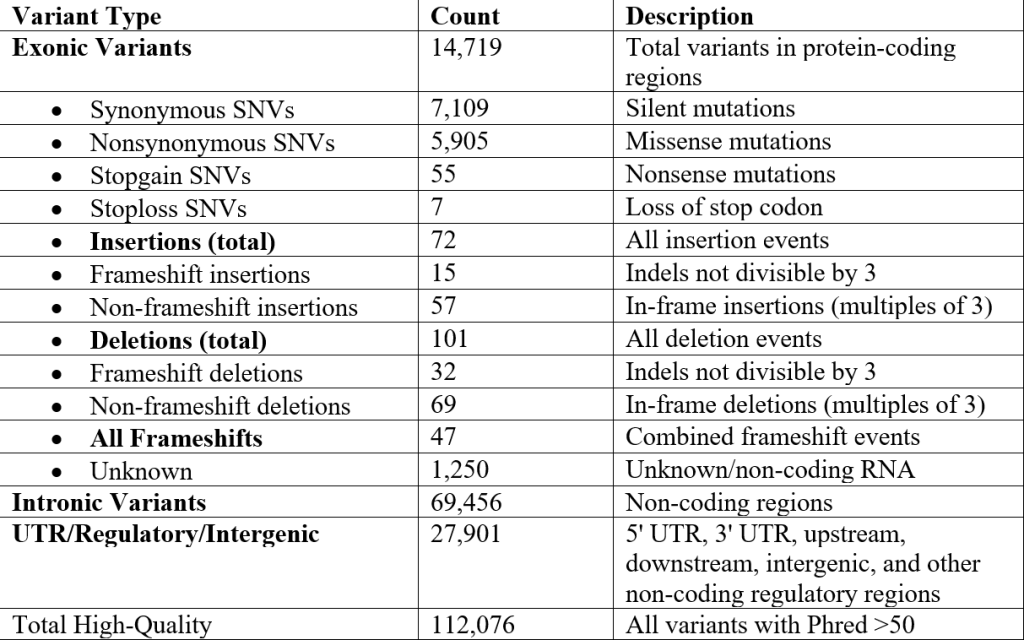

From our alignment, we identified 112,076 high-quality variants (Phred Quality Score > 50) in our sequence. The genome contained 14,719 exonic variants and 174 indel variants, resulting from those high-quality mutations. Out of the exonic mutations, we identified 7,109 synonymous variants, 5,905 nonsynonymous variants, 47 frameshift variants, 72 insertion variants, 15 frameshift insertions, 57 non-frameshift insertions, 101 deletion variants, 32 frameshift deletions, and 69 non-frameshift deletions, displayed in Table 1 below:

A Phred Quality Score is a measure of the accuracy of base calls made during DNA sequencing. A score of 50 or higher represents 99.999% accuracy or 1 base in 100,000 has an error during sequencing.

Each high-quality variant had a quality score greater than 50, which ensures a low chance of mismatches. We then selected 15 specific variations in the genome to focus on, as presented in Table 2. These 15 variations were nonsynonymous SNVs or indels in exonic regions, documented in at least one disease, and noted as pathogenic in the annotation.

Each high-quality variant had a quality score greater than 50, which ensures a low chance of mismatches. We then selected 15 specific variations in the genome to focus on, as presented in Table 2. These 15 variations were nonsynonymous SNVs or indels in exonic regions, documented in at least one disease, and noted as pathogenic in the annotation.

From these 15 mutations, we then selected three particularly intriguing ones to research their implications and diseases further, using their Reference SNP2 (rs) Report15. We ensured that each mutation was on varying chromosomes. Table 3 introduces our findings.

A genetics database for human single nucleotide variations that tracks frequency across populations and effects.

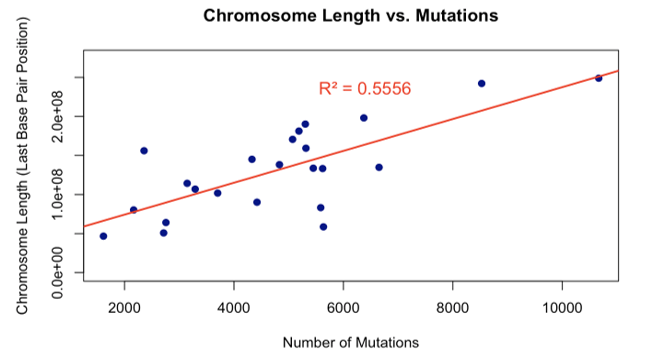

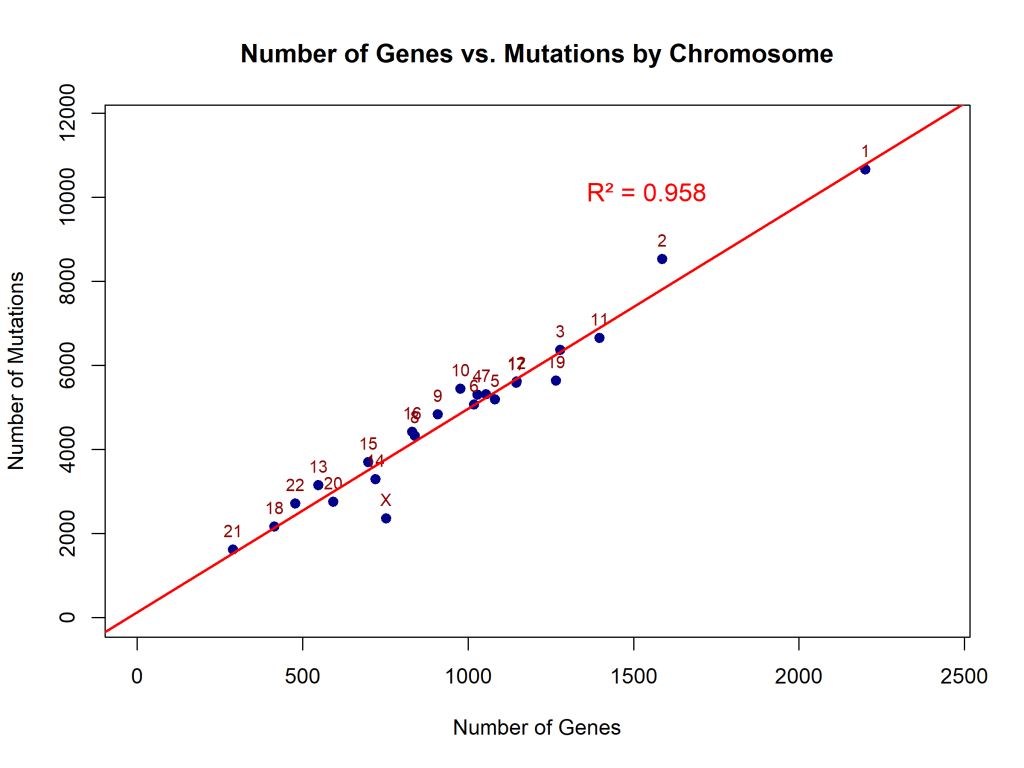

Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate that the number of genes and the length of a chromosome are directly proportional to the number of mutations, since more nucleotide bases have a possibility of changing or mutating. Linear regression analysis demonstrated that mutation count scales proportionally with chromosome length (slope (β₁) = 20,399 bp per mutation, 95% confidence interval(CI): 12,120–28,679, R² = 0.56, p < 0.0001). This indicates that mutations are distributed across the genome in proportion to chromosome size, with chromosome length explaining 56% of the variance in mutation counts (Figure 2). The number of mutations per chromosome also increased linearly with gene count (β₁ = 4.84 mutations per gene, 95% CI: 4.38–5.30, R² = 0.96, p < 0.0001), suggesting that genomic regions with higher gene density accumulate proportionally more variants (Figure 3).

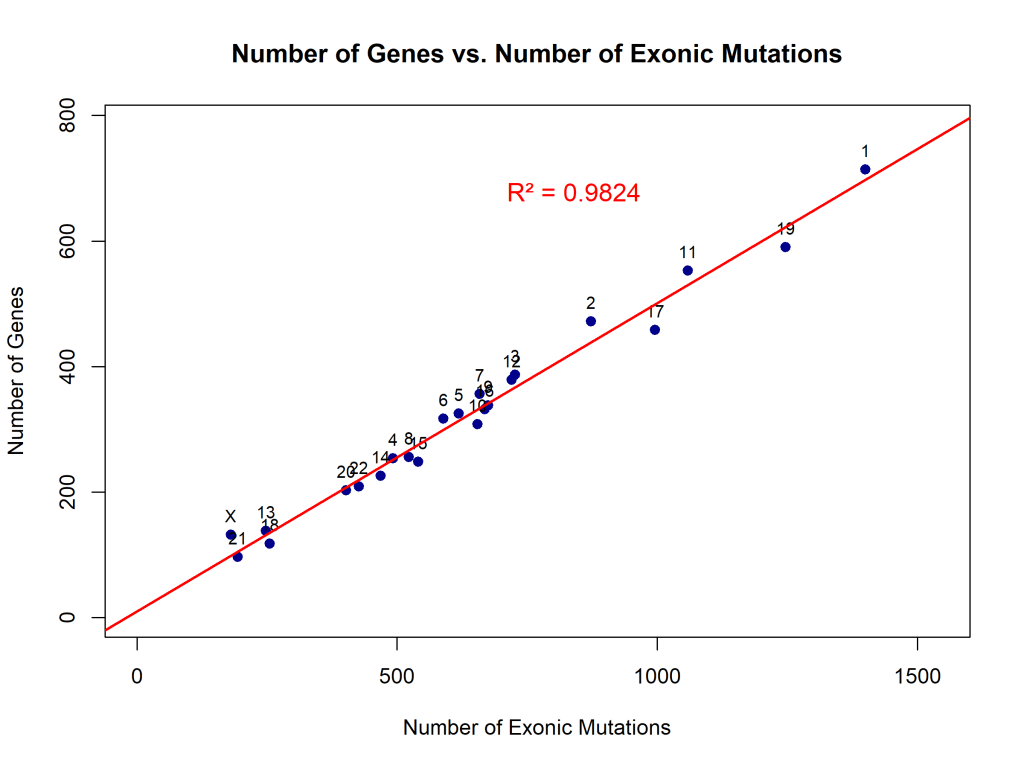

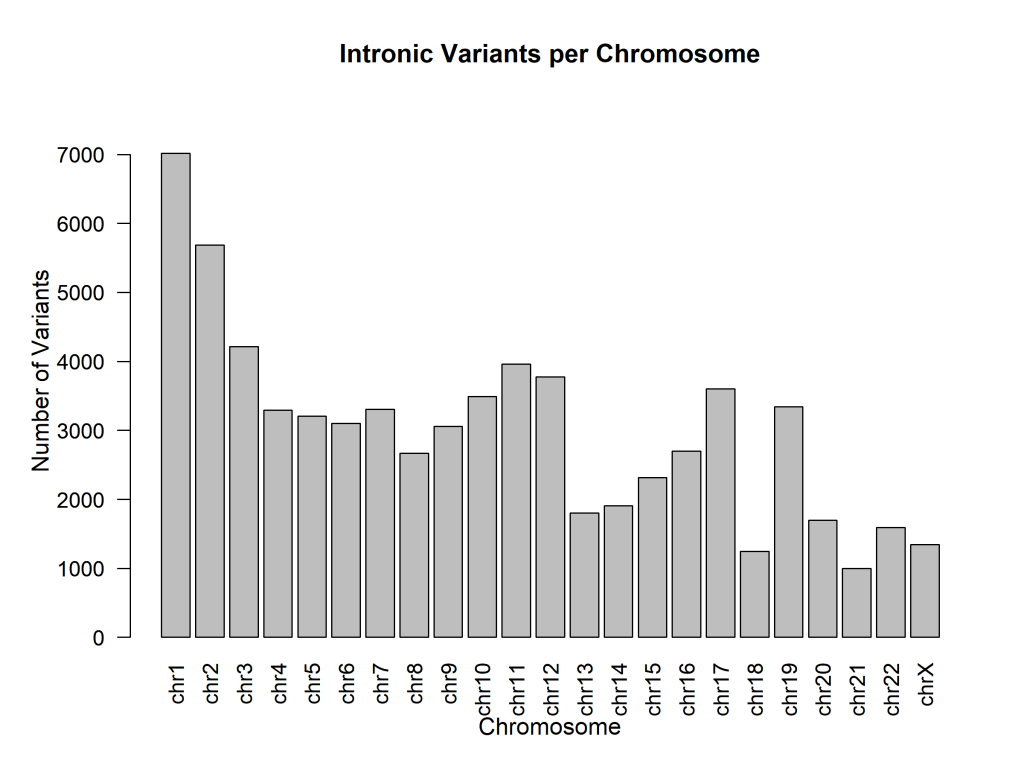

Figures 4, 5, 6, and 7 compare the number of exonic mutations versus intronic mutations for each chromosome and for each gene. Each chromosome presents more intronic variants than exonic variants, which is reasonable since intronic regions are more prevalent. The number of genes is also directly related to the number of intronic and exonic mutations, with a high coefficient of determination. Exonic mutations scaled strongly with the number of genes per chromosome (β₁ = 0.49 genes per exonic mutation, or equivalently, ~2.04 exonic mutations per gene, 95% CI: 0.46–0.52, R² = 0.98, p < 0.0001). The extremely high R² value (0.98) indicates that gene count is an excellent predictor of exonic variant burden (Figure 4). Intronic mutations also correlated with gene count (β₁ = 0.19 genes per intronic mutation, or equivalently, ~5.36 intronic mutations per gene, 95% CI: 0.17–0.21, R² = 0.95, p < 0.0001). The higher ratio of intronic to exonic mutations reflects the larger size of intronic regions in the human genome (Figure 5).

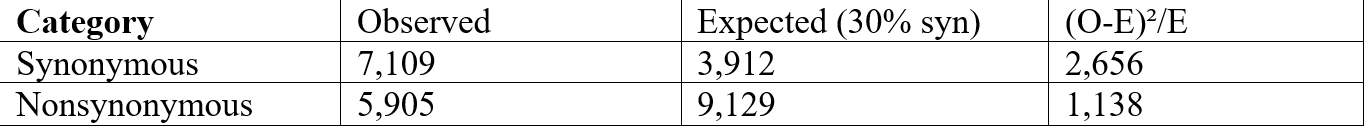

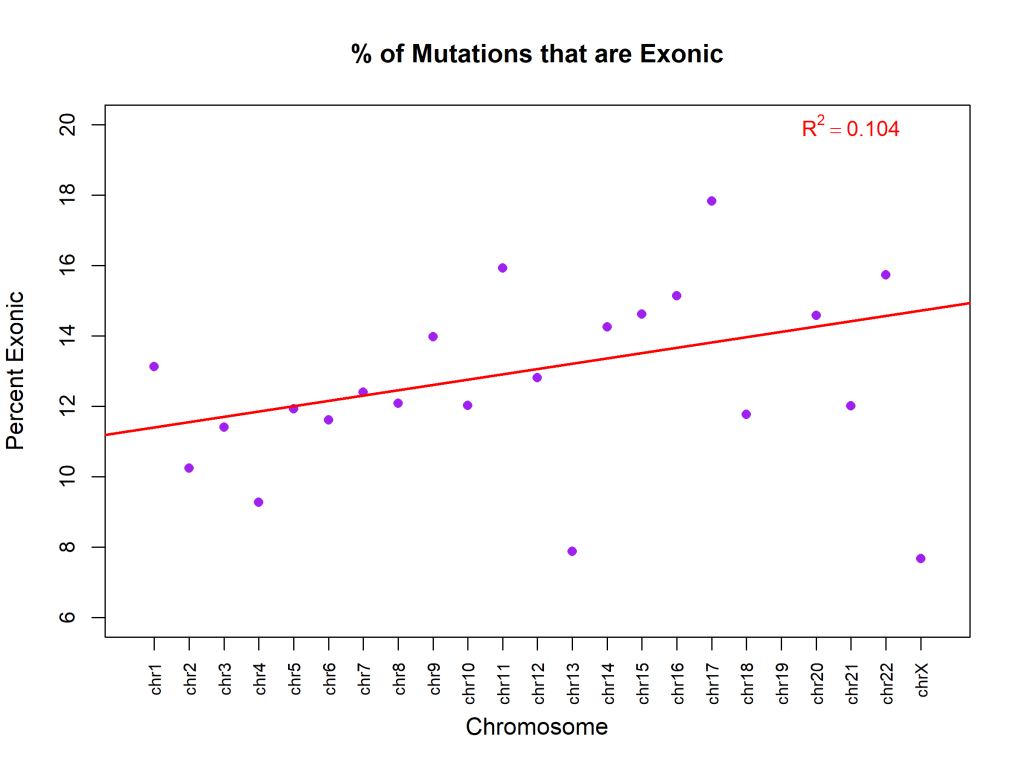

Figure 8 graphs the percent of exonic mutations per chromosome, showing no specific correlation between chromosome and exonic mutations. The percentage of variants classified as exonic showed no significant relationship with chromosome number (β₁ = 0.15% per chromosome unit, 95% CI: -0.05 to 0.35, R² = 0.10, p = 0.13). This indicates that the proportion of exonic variants is relatively uniform across chromosomes (mean ~13%), with no chromosome-specific enrichment or depletion. Figure 9 illustrates the distribution of various types of mutations. Figure 10 exhibits that, although most are synonymous, the number of nonsynonymous ones exceeds the average. Supposedly, “between one-quarter and one-third of point mutations in protein-coding DNA sequences are synonymous”16 .Table 4 demonstrates a Chi-square test to test whether the observed ratio is statistically significant.

x² = 3,794, degrees of freedom = 1, p < 0.0001

The observed ratio (54.7% synonymous) significantly exceeds the expected 25-33% (p < 0.0001). Some possible explanations include that nonsynonymous mutations may be under-represented due to negative selection in the human population, our filtering criteria (Phred >50, depth filters) may have differentially affected the two categories, or the expected ratio from Erickson (2022) was derived from experimental mutation accumulation studies, which may not reflect standing variation in human populations subject to selection.

Discussion

Among the various types of variations, one of the most interesting was a mutation in the HNF1A gene that is historically related to maturity-onset diabetes of youth, abbreviated as MODY3. The HNF1A variant rs1169305 (c.1720A>G) has been submitted to ClinVar in the context of Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young type 3 (MODY3), with historical annotations suggesting a missense change (p.Ser574Gly). However, based on the ClinVar database, this variant is now classified as benign, and its high allele frequency in population databases further supports non-pathogenicity. The variant shows near-fixation in Asian populations (100%) and a global frequency of 99.3%, indicating that the G allele represents the ancestral, common variant. The reference genome’s A allele at this position (0.663% globally) reflects the arbitrary nature of reference sequences, which are derived from a small number of individuals and do not necessarily represent the most common allele in human populations. This finding underscores the critical importance of validating computational predictions against population frequency databases and clinical variant repositories before making pathogenicity claims. Its high allele frequency in population databases further supports non-pathogenicity. MODY3 is a hereditary form of diabetes that stems from mutations in the HNF1A gene. While the HNF1A gene typically makes a protein (hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha) that helps pancreatic cells detect sugar and release insulin, the HNF1A mutations produce faulty proteins that cannot properly activate genes necessary for glucose sensing and insulin production in pancreatic cells. As a result, these mutations inhibit the cells from detecting high blood sugar and releasing adequate insulin.The primary defect is early-onset diabetes due to progressive pancreatic failure. If such an individual’s blood sugar is not well controlled, they can develop serious complications, including kidney damage, eye problems, nerve damage, and occasionally liver tumors.

An example of a case study about MODY3 involved two different patients17:

- Patient 1: a 23-year-old man with a start codon mutation in the gene, which prevented him from producing the protein.

- Patient 2: a 19-year-old woman with a frameshift mutation in the gene; she produced a broken, shortened protein that was nonfunctional.

Patient 1’s diabetes was caught early on, and once doctors identified his genetic type, he responded well to diabetes pills and maintained good health with no complications. However, Patient 2 had suffered for 7 years without proper treatment and had already developed serious nerve and kidney damage before finally receiving insulin therapy. The difference in their quality of life underscores the importance of early genetic testing, especially for MODY3 patients. Unlike regular diabetes, this genetic variation responds much better to specific medications, but only under the circumstance that doctors exactly know what kind of disease they are treating.

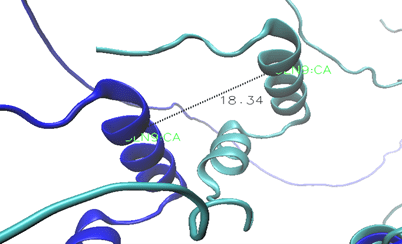

Next, we modeled the gene using AlphaFold v2.3.218 and visualized it using VMD to obtain a better understanding of this mutation (Figure 11).

The dark blue model is the mutated model, and the light blue is the normal gene. Since the gene has not been experimentally analyzed yet, both models were created by AlphaFold as a hypothesis of its structure. Both models are aligned with each other. The orange is glycine, and the gray is serine. While the structures seem similar, the following key differences were identified:

- The entire gene has drifted outward, revealing a weaker structure.

- Shifting dynamics affect the interactions the protein would have otherwise.

- The full shifting of the gene could indicate unstable structure and disrupted binding sites.

The variant identified in this study (p.Ser574Gly) is located at residue 574 within the C-terminal transactivation domain, approximately 300 residues downstream from the DNA-binding region. This domain is responsible for recruiting transcriptional co-activators rather than direct DNA contact. Figure 12 demonstrates the extent of this shift on the shape of the protein.

The offset between these two ɑ-helices is 18.34Å, which is significant in a molecule because of its small size (Figure 12). However, given the low model confidence and the variant’s location outside the DNA-binding domain, we cannot conclude that this displacement directly affects DNA binding or causes disease, but it does change the structure of the protein. AlphaFold modeling of the wild-type and variant HNF-1α proteins yielded an overall confidence score (pLDDT) of approximately 53. While this represents low confidence overall by AlphaFold standards (scores >90 = high, 70-90 = good, 50-70 = low), it is important to note that confidence varies substantially across different protein regions. Critically, residue 574 is located within a predicted α-helix, a regular secondary structure element that AlphaFold models with greater reliability than disordered regions. We therefore present this structural analysis as a hypothesis-generating approach that could guide future experimental work, rather than definitive evidence of pathogenicity. The observed 18.34 Å displacement represents a testable prediction that requires experimental validation.

Limitations

There are few limitations of our study, ranging from ethical to computational. While the overall AlphaFold confidence score was moderate (53), the variant residue (574) is located within an α-helix, a structured region where AlphaFold predictions are more reliable (65-75). Nevertheless, the predicted structural displacement represents a computational hypothesis requiring experimental validation. The overall shape is present, but the turns still require investigation. In addition, this model is a snapshot of a dynamic structure that continuously changes, which could amplify the differences between the two models. AlphaFold models are computational predictions, not experimentally determined structures.

Furthermore, sequencing errors during replication are a potential limitation of sequencing by next-generation sequencing (NGS)19. The Phred score, although used as a filter to include only mutations with a score larger than 50, still indicates a probability that the base calls are unreliable, which leads to false variant identification. Sequencing errors during replication could potentially misclassify benign variants as pathogenic or miss MODY3-causing mutations20.

Personal genomics is also a significant ethical concern21. Genetic information that reveals a disposition to diabetes also affects the family of the patient since they share the same inheritance pattern; there are contradicting opinions on the publication of such data. Furthermore, misuse of data could lead to genetic discrimination and potentially endanger the patient22.

Some downsides of genomic studies are that the data only presents the risk of having a disease without certainty, or data can have low coverage and still remain uncertain. A major caveat to studying human genomes is the legal complexities that accompany it. On one hand, personal genomics is the gateway to the center of a human’s data and could be used for commercial purposes, but on the other hand, understanding this level of the disease would be game-changing in a clinical setting. For example, doctors could provide personalized healthcare, such prescribing sulfonylureas to support the protein in the action of releasing insulin instead of simply prescribing insulin23.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insights into the structural and functional impacts of the HNF1A mutation, demonstrating how computational modeling and genomic analysis can inform personalized treatment strategies. From the first base pair to 3 billion, a total of 120,000 variants is present within this sample human genome, 15 of which were associated with unique diseases. We narrowed these variants to research a mutation in the HNF1A gene, which is analyzed in relation to MODY3 as a proof-of-concept for structural modeling. This condition is sensitive to sulfonylureas and can be treated effectively if identified in a clinical setting. Our study explores new ground for this protein by visually examining its mutations, which allows the structural differences to be observed. Although computational confidence was moderate, this approach presents a proof-of-concept computational pipeline for genome-scale variant identification, annotation, and structural modeling for analyzing the source of a genetic disease.

Data Availability Statement

Raw sequencing data are publicly available from the 1,000 Genomes Project (SRR701471), or at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/SRR701471. Processed data (VCF files, annotated variants) and analysis scripts in R are available at https://github.com/sophia0805/BIOS10007-Final. The software versions used are as follows: BWA v0.7.17-r1188, SAMtools v1.6, ANNOVAR downloaded 03-2023, AlphaFold v2.3.2, and R v4.2.1. We used GRCh37/hg19 (hs37d5) as the human reference genome. All analyses were performed on Midway3 cluster (University of Chicago RCC). Both wild-type and mutant (p.Ser574Gly) HNF-1α protein structures were predicted using AlphaFold v2.3.2. Due to file size limitations, the original PDB model files are not permanently hosted, but can be fully reproduced using the AlphaFold pipeline (https://github.com/deepmind/alphafold) with the HNF1A protein sequence (UniProt: P20823, isoform 1) for wild-type, and the same sequence modified at position 574 (Ser to Gly) for the mutant model. The input sequences and AlphaFold parameters used are provided in the GitHub repository to ensure full reproducibility.

References

- M. Adams, C. Fields, J. C. Ventor (eds). Automated DNA sequencing and analysis. Academic Press, London, San Diego, 1994. [↩]

- The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. Vol. 526, pg. 68–74, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393 [↩]

- O. Devuyst. The 1000 Genomes Project: Welcome to a new world. Peritoneal Dialysis International. Vol. 35, pg. 676-677, 2015, https://doi.org/10.3747/pdi.2015.00261 [↩]

- Y. Miyachi, T. Miyazawa, Y. Ogawa. HNF1A mutations and beta cell dysfunction in diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. Vol. 23, pg. 3222, 2022, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23063222. [↩]

- Q. Wen, Y. Li, H. Shah, J. Ma, Y. Lin, Y. Sun & T. Liu. Two case reports of maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 caused by the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α gene mutation. Open Medicine, Vol. 18, pg. 20230705, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2023-0705. [↩]

- C. Bellanné-Chantelot, D. J. Lévy, C. Carette, C. Saint-Martin, J. P. Riveline, E. Langer, R. Valéro, J. F. Gautier, Y. Reznik, A. Sofa, A. Hartemann, S. Laboureau-Soares, M. Laloi-Michelin, P. Lecomte, I. Chaillous, D. Dubois-Laforgue, J. Timsit, French Monogenic Diabetes Study Group. Clinical characteristics and diagnostic criteria of maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) due to molecular anomalies of the HNF1A gene. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. Vol. 96, pg. E1346–E1351, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2011-0268 [↩]

- Research Computing Center, University of Chicago. Midway3. https://rcc.uchicago.edu/midway3, 2021. [↩]

- P. J. Cock, C. J. Fields, N. Goto, M. L. Heuer, P. M. Rice. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Research. Vol. 38, pg. 1767-1771, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkp1137. [↩]

- H. Li, R. Durbin. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. Vol. 25, pg. 1754–1760, 2009. [↩]

- K. M. Robinson, A. S. Hawkins, I. Santana-Cruz, R. S. Adkins, A. C. Shetty, S. Nagaraj, L. Sadzewicz, L. J. Tallon, D. A. Rasko, C. M. Fraser, A. Mahurkar, J. C. Silva, J. C. Dunning Hotopp. Aligner optimization increases accuracy and decreases compute times in multi-species sequence data. Microbial Genomics. Vol. 3, pg. e000122, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000122. [↩]

- P. Danecek, J. K. Bonfield, J. Liddle, J. Marshall, V. Ohan, M. O. Pollard, A. Whitwham, T. Keane, S. A. McCarthy, R. M. Davies, H. Li. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience. Vol. 10, pg. giab008, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008. [↩]

- B. Ewing, L. Hillier, M. C. Wendl, P. Green. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. 1. Accuracy assessment. Genome Research. Vol. 8, pg. 175–185, 1998. [↩]

- B. Ewing, P. Green. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. 2. Error probabilities. Genome Research. Vol. 8, pg. 186–194, 1998. [↩]

- K. Wang, M. Li, H. Hakonarson. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from next-generation sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research. Vol. 38, pg. e164, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkq603. [↩]

- S. T. Sherry, M. H. Ward, M. Kholodov, J. Baker, L. Phan, E. M. Smigielski, K. Sirotkin. dbSNP: The NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Research. Vol. 29, pg. 308-311, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [↩]

- A. V. B. Margutti, W. A. Silva, D. F. Garcia. Maple syrup urine disease in Brazilian patients: Variants and clinical phenotype heterogeneity. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. Vol. 15, pg. 309, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-020-01590-7. [↩]

- Y. Zhang, Y. Liu, Y. Wang. Two case reports of maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 3 caused by the hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α gene mutation. Open Medicine. Vol. 18, pg. 20230749, 2023, https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2023-0749. [↩]

- J. Jumper, R. Evans, A. Pritzel, T. Green, M. Figurnov, O. Ronneberger, K. Tunyasuvunakool, R. Bates, A. Žídek, A. Potapenko, A. Bridgland, C. Meyer, S. Kohl, A. J. Ballard, A. Cowie, B. Romera-Paredes, S. Nikolov, R. Jain, J. Adler, D. Hassabis. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. Vol. 596, pg. 583–589, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [↩]

- H. Satam, K. Joshi, U. Mangrolia, S. Aghoo, G. Zaidi, S. Rawool, R. P. Thakare, S. Banday, A. K. Mishra, G. Das, S. K. Malonia. Next-generation sequencing technology: Current trends and advancements. Biology. Vol. 12, pg. 997, 2023, https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12070997. [↩]

- M. Tosur, I. H. Philipson. Precision diabetes: Lessons learned from maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY). Journal of Diabetes Investigation. Vol. 13, pg. 1465–1471, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1111/jdi.13860. [↩]

- J. Mathaiyan, A. Chandrasekaran, S. Davis. Ethics of genomic research. Perspect Clin Res. Vol 4, pg. 100-104, 2013, https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.106405. [↩]

- K. B. Brothers, M. A. Rothstein. Ethical, legal and social implications of incorporating personalized medicine into healthcare. Personalized Medicine. Vol. 12, pg. 43–51, 2015. [↩]

- K. I. Kendig, S. Baheti, M. A. Bockol, T. M. Drucker, S. N. Hart, J. R. Heldenbrand, V. Dinu. Sentieon DNASeq variant calling workflow demonstrates strong computational performance and accuracy. Frontiers in Genetics. Vol. 10, pg. 736, 2019, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2019.00736. [↩]